Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Benoît Gallot, Author of The Secret Life of a Cemetery

Buddhist koan lovers play a philosophical game that puts forward this challenge: state one truth about the universe that can be proven without a doubt.

And often, “that we will surely die” comes back as a response. But what is death? If you lie down and die under an apple tree, your decaying body nourishes that tree and becomes part of its branches, blossoms, and fruit. Not death at all—you continue to live in that tree. What a lovely thought.

Today’s interview with Benoît Gallot takes us to death central in the city of light: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise, one hundred acres, one million bodies, and until 2011, no plants or signs of life between the gravesites to be nourished by all that decomposing flesh. Yes, Père-Lachaise was deader than a coffin nail until Paris got serious about managing its parks, cemeteries, and other public spaces without the use of pesticides.

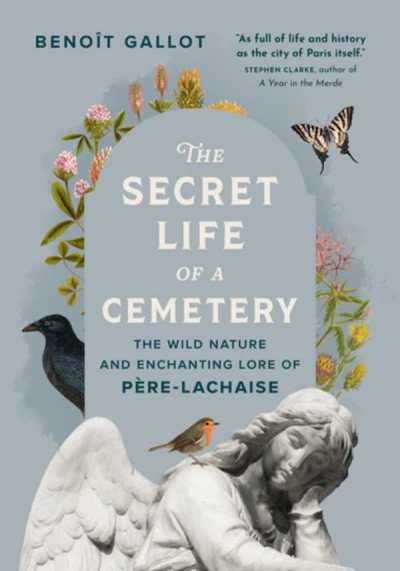

Benoît is the curator at Père-Lachaise. He joins Foreword This Week to talk about his very special new book describing the wildflowers, butterflies, foxes, martens, birds, and “natural splendor emerging amid the vast expanse of graves, tombs, and monuments,” in the words of Meg Nola in her review of The Secret Life of a Cemetery. “With genial pride and compassion, [Benoît] serves as an engaging guide through Père-Lachaise while contemplating universal matters of death, remembrance, and regeneration. … The Secret Life of a Cemetery is a historical and cultural delight.”

Secret Life was part of the Gift Ideas feature in Foreword‘s May/June issue along with four other books. Free digital subscriptions are just a couple clicks away, don’t delay.

Can you describe the contrast in how the cemetery grounds of Paris looked prior to the city’s 2011 decision to reduce pesticide use, compared to the gradual biodiversity changes that began to occur after that initiative?

Before 2011, there was no trace of life between the graves: pesticides killed any wildflowers that sought to thrive there. Parisian cemeteries were already heavily wooded, and some areas were adorned with flowerbeds tended by gardeners. But the cemetery divisions were overwhelmingly mineral. Any trace of life around the graves was seen as a lack of respect for the dead.

In addition to discontinuing the use of plant control products, there is now an active policy to develop the shrub and herbaceous layers (ie, grasses, ferns, and wildflowers) to complement the existing tree layer. Every year, we “grass” sidewalks and pathways inside the cemetery divisions by removing the concrete slabs, which promotes soil permeability and the emergence of flora.

This approach, which is more environmentally friendly and less toxic to cemetery users, encourages the return of animals: foxes and birds of prey, but also less visible species such as butterflies, wild bees, and other insects.

In the book you note how “most people still have a distorted vision” of Père-Lachaise, “based on preconceived notions and fantasies of all kinds.” What are some of those misperceptions and myths?

Many people have the preconceived notion that Père-Lachaise is no longer a functioning cemetery, or that burials are reserved only for a few famous people. However, it’s the busiest burial site in France! Each year, 6,500 cremations, 1,700 burials, and 1,300 scatterings of ashes take place there. Stonemasons, engravers, and gravediggers work every day to allow families to bury their loved ones and mourn their loss.

My teams spend a lot of time reminding people that, before being an open-air museum or a landscaped park, Père-Lachaise is above all a functioning cemetery. And the heart of my job is to keep this cemetery alive by reclaiming old, abandoned graves and redividing vacant plots so that new Parisian families can use them. This is also why we strictly prohibit all activities that could disturb the peace of the place and prevent mourning families from gathering: jogging, escape games, recreational activities, and so on.

Furthermore, Père-Lachaise is a very unusual place in Paris. As soon as you walk through the doors, you enter another world, a city within the city, made of aged stones adorned with various symbols and inscriptions of all kinds. This complete change of scenery gives some people the feeling of entering a new universe where reason no longer has a hold. Many people think that the place is haunted; not a week goes by without someone asking me if I see ghosts or paranormal phenomena. Some guides feed into these fantasies and even make a business out of them. But my experience as a curator has shown me that all these legends belong to the place, whether we like it or not! They fascinate people, some of whom even come to Père-Lachaise because of its myths. The tomb of Victor Noir is said to have the power to help infertile couples conceive; the tomb of Allan Kardec, founder of the Spiritist philosophy, will make your wishes come true; the tomb of Countess Demidoff allows you to inherit her fortune by spending a full year next to her coffin. I also regularly find traces of voodoo rites: a severed sheep’s head placed in the hollow of a tree; knives with inscriptions on the blades stuck in a grave; Barbie dolls wrapped in a bloody stocking and tied to a tree …

All of these stories and legends contribute to making Père-Lachaise a fascinating and extraordinary place.

The book includes wonderful descriptions of the wildlife found within the cemetery, from raucous crows and “tawny” owls, to magpies, martens, and cats lounging on headstones. But your interactions with the foxes living at Père-Lachaise are noted with exceptional detail, particularly as you recall how you made your first fox sighting there during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Amid global fear and uncertainty, the cemetery had become a “closed-off necropolis,” where the bodies of pandemic victims arrived regularly. Yet your sudden glimpse of fox cubs “frolicking among the graves” brought a sign of renewal and emergence. As you photograph these animals for your cemetery Instagram account (@la_vie_au_cimetiere), do you have a daily routine that you follow—along with a way of managing to both interact and coexist without disrupting them?

Wildlife photography has become a real passion for me! However, Père-Lachaise hasn’t become a zoo, and successfully photographing these animals requires a lot of patience, especially since I don’t cheat by using food to bait them, for instance. I don’t have a preferred technique: some evenings I wander randomly through the cemetery paths hoping to spot a fox sleeping on a grave or fox cubs playing. Other times, I stay hidden, hoping to see an animal pass by. What I love is that every outing is different. I never know what to expect, which is very exciting. Sometimes I wander for two hours without seeing any animals, or only spotting one furtively, and sometimes in thirty minutes I’ll get fantastic shots.

I always try to stay invisible, to make myself a ghost so as not to disturb the animals. I have many photos of foxes sleeping on graves who never spotted me. When the foxes do see me, I try not to bother them by staying far away and leaving after a few shots. If the foxes ever become less timid and let themselves be photographed too easily, I think I would be disappointed. Even the cats in the cemetery are for the most part very wild, and successfully photographing them remains a real challenge. As for birds, with them, you have to be especially responsive with the camera to capture the moment. It requires real technique.

Looking back, I have improved over time, both in my approach and in my photographic techniques. But even when I don’t get any good shots or see any animals, wandering alone in the middle of forty-three hectares is an experience I’ll never get tired of!

The American singer Jim Morrison of The Doors is buried at Père-Lachaise, and since his 1971 death hordes of fans have flocked to his grave and left a variety of offerings. But you note how there are many other beloved and famed residents of the cemetery, and how visitors of different nationalities often go to the graves of their countrymen or women: “Poles honor the memory of Frédéric Chopin; Kurds pay their respects to singer Ahmet Kaya and filmmaker Yilmaz Güney; Italians visit the graves of Luigi Cherubini and Amedeo Modigliani; the Irish and the English are drawn to the emasculated sphinx on Oscar Wilde’s tomb.” Are there any unique memorial items left at these graves that reflect their cultural or national identities?

On Chopin’s grave, there are often Polish flags or red and white candles. It’s perhaps the grave where national identity is most prominent, thanks to the colors of Poland’s flag in the various objects placed there. For Jim Morrison, there are pieces of chewing gum on a tree (why, I have no idea!) and all sorts of miscellaneous items that don’t particularly reference the United States but instead reflect the singer’s world.

For Oscar Wilde, it’s the same; there are letters, notes, photos, or lipstick kisses on the protective glass, with no reference to Ireland. Admirers come from all nationalities and develop a strong attachment to Oscar Wilde as a person and to his writings. On the other hand, cultural and national references are much more visible on memorials honoring foreign fighters who died for France, for instance, or on the monument to the Spanish Republican Guard. This makes sense, and a number of commemorations take place each year at these graves, organized by the embassies in France.

You write that you envision your own grave as a “place full of life,” with a small garden and a rainwater trough for foxes and birds, while “a QR code would link to my Instagram account so that people could continue to ‘like’ me in death.” As technology continues to become a major part of our everyday lives, do you think that QR codes and interactive virtual features will be included in grave design? And in considering the more intrusive aspects of social media and technology, does the cemetery have any prohibitive policies about making TikTok videos or taking selfies on the grounds?

QR codes are becoming more common and are quite discreet on graves. I think it’s a good, quiet, and understated way to pay tribute to the deceased. However, I hope that screens won’t invade Père-Lachaise Cemetery or the graves themselves. You could imagine flat screens replacing the granite boxes in the columbarium, but that would be a real shame! I like the idea of Père-Lachaise remaining timeless. As soon as you enter, you forget it’s 2025, and it needs to stay that way to preserve its “soul.” We’ll soon be updating some of the cemetery’s signage, and we wanted it to remain as discreet as possible. It sounds paradoxical, but it’s important that Père-Lachaise remains a place where you can get lost.

As for videos, there are indeed rules: all professional filming (film, television, influencers, etc.) must receive proper authorization or else face a fine. On the other hand, many tourists take videos or selfies in front of graves. This is a phenomenon that’s futile to fight. As long as it’s done discreetly and respectfully, cemetery staff don’t intervene. Of course, it’s forbidden to climb on the graves or enter the funeral chapels. The vast majority of users naturally adopt respectful behavior, and that’s a good thing.

Though Père-Lachaise is surely distinctly beautiful year-round, are there any particular months or seasons that might be the best time for tourists to visit the cemetery?

It’s very subjective. Personally, I love spring because life is exploding everywhere, and it’s a fascinating display every year. Autumn is also a time of year I’m very fond of, because of the special All Saints’ Day period, but also because of the different colors of the leaves on the trees. Summer and winter are periods I enjoy less. But what I really love is seeing the cemetery evolve over the course of the seasons—ultimately, in accordance with the cycle of life.

Meg Nola