Reviewer Luke Sutherland Interviews Syr Hayati Beker, Author of What a Fish Looks Like–Foreword This Week

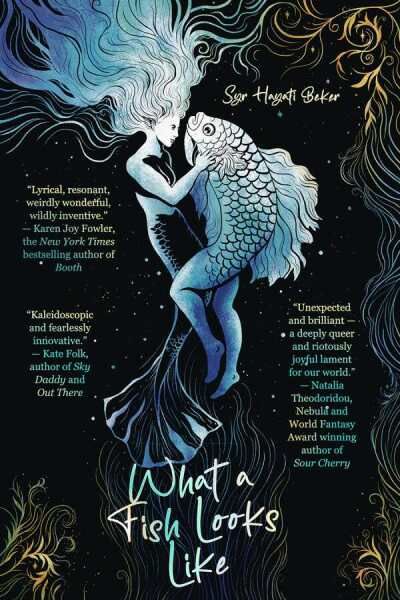

“Syr Hayati Beker’s gleaming novella What a Fish Looks Like alchemizes confessional notes and remixed fairy tales to tell a story of queer survival amid ecological disaster. … passed notes, party invitations, and other ephemera appear between inventive riffs on classic stories like Beauty and the Beast. The cumulative effect is intimate, voyeuristic, and rewarding.’’ —From Luke Sutherland’s Starred Review

We’re giddy about this interview, it exemplifies why we bring together reviewers and authors to help us understand an incomprehensible world. In their answer to Luke’s question about what compels so many queer writers to wade into the distressing subject of climate change, Syr jokes that queer writers were all perhaps bitten by a radioactive spider and then speculates that the otherworldliness of queer existence mimics a planet at odds with itself. In other words, the queer community is able to keep their shit together through these apocalyptic times because they have witnessed their own bodies go off the rails, and it’s nothing new to them.

Syr is a very, very special thinker, and this conversation, which is fascinating in a heartbreaking way, will keep you thinking for weeks.

Many post-apocalyptic novels are catalyzed by a single catastrophic event, like a plague or a global war. In What a Fish Looks Like, we’re presented with a world that ends in stages, disasters that interlock and layer on top of each other in real time. What does this approach bring to our cultural and literary understanding of “apocalypse?”

Apocalypses are so intimate. They reveal so much about us.

I am definitely not here to cancel the monogamopocalypse! I grew up in the 1990s–2000s, and single apocalyptic stories are part of my DNA. I will always have Will Smith running around emptied museums, giant spaceships in the air, a zombie horde (fast or slow) on the horizon. I love the fantasy these narratives offer: sure, maybe New York is gone, but so are parking meters, taxes, the production cycle. They connect us, maybe prepare us, for the dream of a post-capitalist, post-social media world where time works differently and the power dynamics have shifted, and maybe we can learn to knit again.

Monopocalypses can be weird, wonderful, liberatory: I’m thinking of Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (of course), Larissa Lai’s Tiger Flu, Anne Washburn’s play Mister Burns, which is about community and the evolution of story in a post-electrical world.

There are a lot of reasons the one-apocalypse didn’t work for me: first, even for a theater queer, flaming sword angels just felt a little too-too. Second, like my character Seb, I don’t have your traditional apocalyptic skills: I’m petty, messy, I like cats and books, I’m not good with a baseball bat. I learned enough from the ableism that flared up 2020-now that I don’t want a survival-of-the-sixpack-iest kind of apocalypse because everyone I love just wouldn’t be there. I also don’t think the world stops changing, even under, eg, The Road, I want to believe there are strangenesses in our world that can’t be repaved.

I also know that what we so pithily call climate change isn’t a single meteorite headed for my own head. It’s a series of catastrophic events that affect us all differently, but that we must be responsible for together. Twenty years post-Katrina, we have to take that lesson.

I think about all the times I’ve heard the saying: It’s not the end of the world, meaning that, relatively speaking, one should stop whining. What if instead we allowed the possibility that there are ends of the world happening all the time, and what if they are all connected and constantly emerging? Daisy Hildyard’s phenomenal book The Second Body imagines into that question with so much empathy: I am here in Oakland, but my body is also an underage mine worker, a collapsing bee colony, a shark in a net. What if all of these things were just as real and relevant as apocalypses: the heartbreak of my neighbor who lost their cat, the spider whose web I shot down with a garden hose, the earthquake in Afghanistan? What if, as physicist Karen Barad theorizes, “Matter feels, converses, suffers, desires, yearns, and remembers,” and we are in collaboration with climate change?

One of my favorite recent books is B. Pladek’s Dry Land, which examines the question: what if we can’t preserve the world? What then? Along those lines, I wanted to ask: what if the apocalypse happens and the world doesn’t end, or what if only a tiny part of the world, one that you were particularly attached to, ends? The queers in my book are experiencing their great and tiny apocalypses while the great and tiny apocalypses rage on outside. They also experience their great and tiny moments of whatever could be the opposite of an apocalypse: euphoria, triumph, curiosity, community, desire, and delight.

And what I found, and tried to explore in this book, is that when you take away the binary of a single apocalypse, and the question of whether we are strong enough to survive, you get so many other things: the possibility of survival; the possibility of survival but being forever changed; the possibility of the world going on without us; the possibility that on a date with someone you happened to match with on an app, you stop kissing long enough to look up at the night sky and admire the light evidence of someone else’s apocalypse, hundreds of thousands of miles across space and time.

Like the layering of the plot, the structure of the book comes together through accumulation: letters, party invitations, and other ephemera show up alongside stretches of more traditional narrative. How did you start writing in such a fragmented style? Did you always envision the whole that each piece was building towards, or did the accumulation begin without an end in mind?

Here comes a plea Foreword readers will appreciate: support our ecosystem of independent presses!

I owe so much to my press, Stelliform, and especially the editor Selena Middleton. The idea of a climate change book told in margin notes and ephemera collected between the pages of a book of fairy tales that a community is passing around—this is the kind of pitch that could get you laughed out of a room. Selena didn’t just not laugh. She didn’t ask me to simplify, she encouraged me to go deeper, to create this community, and then she went in and defied the laws of form and formatting to create a book told in letters, margin notes, notes scrawled on paper, flyers, there’s a whole section told in graffiti on a bathroom wall, six original illustrations by real-life artist/activist Zeph Fishlyn. There’s a madlib, a postcard, and a secret spider, there’s even a Red Riding Hood told from the point of view of mycorrhizal networks.

As for the why, I was at Fogcon the year Donna Haraway was a guest of honor. In her keynote, which was based on her book Staying with the Trouble, she said: “It matters what knots knot knots, it matters what worlds world worlds, it matters what stories story story.” It felt like someone was speaking directly to me in my own neurofabulous language, and confirmed this thing that I had always felt, that the shape of a story is as alive as a story, and can be a kind of portal to the biggest questions you can ask.

I am inspired by writers who queer form to tell the story they need to tell, like Anne Carson’s Nox, which tells a story about grief in the shape of a box of letters and poems that get shuffled around so that disorder is the point, or like Kazim Ali, who translates his own hybridities into texts that defy form, or like Steven Hall’s Raw Shark Texts, that literally makes a shark appear out of words! There is also such a rich lineage of writers who have made form playful, remade language into a form of drag or subversion or decolonization (Kamau Brathwaite, Aimé Césaire, Patrick Chamoiseau, Julián Delgado Lopera), and I feel so lucky their books found me.

For What a Fish Looks Like, I had big questions about memory, belonging, community, and storytelling. I want to believe that collective liberation, and surviving climate change, means all of us are needed, and all of us belong, so I tried to make a form that allowed that. When I built my narrative, I was thinking about Anna Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World, and her fascination with assemblages of life forms brought together by disruption. Also I am nosy and I’m always so tempted to read other peoples’ letters. My biggest hope is that the book feels playful, gossipy, and that readers feel welcomed into the world of the book. I want people to write in it, pass notes to one another. I want the form to be conscious of the fact that stories evolve after they are told. I hope readers know they are part of that co-creation.

The book is haunted by loss, from queer breakups to extinct species. Characters, particularly recent ex’s Seb and Jay, take totally different approaches to grief. Some become mired in the past; in the title chapter, one even volunteers to use their body as a living conduit for polar bear DNA. Others throw themselves into activism and the steadfast optimism it requires. Why was it important to you to depict such diverse reactions to disaster?

This is a particularly beautiful question to me because I want to imagine a world in which we all belong, and where no reaction to climate change, loss, change, or even fascism, is the only right response.

As a queer person who has spent time in activist circles, I also see how we can sometimes narrow one another in those moments. We question the how of our activism, we cut one another off, we limit ourselves and one another out of fear, we question whether rage or sadness or numbness or activism or violence or peace is a correct response, and we let the fear and rigidity bleach out the coral reef of our movement: the joy and multiplicity and riotousness that could make the revolution irresistible, to quote Toni Cade Bambara. My guides out of this are writers like Kai Cheng Thom, adrienne maree brown, and Margaret Killjoy, who writes: if the world were ending tomorrow, I’d plant a tree.

I am also interested in the ways that climate change, and disaster, puts pressure on different forms of hope and different ways of surviving. I also want to believe there is room in the apocalypse for people who are terrified and petty 99.99999 percent of the time but who do one right thing, like the main character in my retelling of Antigone, or whose main contribution is memory, like the main character in my reverse-Beauty and the Beast who may or may not be turning into a polar bear. My book contains activists who protest, activists who follow in the “Be gay do crimes” lineage, and people whose activism is just being able to create a loving space, even if they’re cranky about it.

And part of this, I think, is honoring that wonder, memory, or grief, alone, could be enough of a response. CMarie Fuhrman, who co-edited Cascadia, said at AWP 2022 that humans have no functional use on this planet other than to praise and wonder at the natural world, and this should be our responsibility. If so, then maybe then it could also be enough to listen, remember, dance, or blow up a pipeline.

There is also a meta quality to the book, in that the practice of storytelling itself is put under scrutiny. In one letter to Seb, Jay writes: “Stories indoctrinate us into abstraction: honor, valor, kindness, loyalty, country, Earth, home.” How do you level the inherent abstractions of narrative with the very real threats you’re writing about? In other words: why write fiction about the climate?

This is a question I can talk about forever. I was so lucky to grow up with storytelling. My father was a great storyteller. He was Turkish and also tried hard to assimilate into US and French/European culture. He overlaid stories of Nasredding Hoja with stories of Popeye, and used both to hide the stories he didn’t want to tell. I also had my mother and a lot of aunties who traded in the currency of gossip, and it was good gossip. My mom is the greatest storyteller I know.

When the various religions I grew up around spat me out, I would always end up in book sales outside churches. I would pull up these old fairy tale books that felt very pagan and heretical and revolutionary, and the stories I found there felt like portals to a spiritual place. So after I read all the stories I could, I studied the great storytellers, like Ruth Sawyer and Zora Neale Hurston, and later I became a storyteller and told stories in parties and on stages. I believe that storytelling, including gossip, is a community ritual that has real transformational magic in it.

Along the way, I learned that there is a kind of violence to storytelling, to capturing and preserving stories, and to fairy tales, even if you’re using them to write yourself back in. My character Jay takes Seb to task on this: Andrew Lang stole stories from across the empire. He didn’t write his fairy tale books. His wife did. She was the heir to a plantation in Barbados. The Grimm brothers stole stories. Zora Neale Hurston, one of our greatest storytellers and story catchers, studied with Margaret Mead and Franz Boas, who gave us some really problematic ideas, along with the notion that you can kind of specimen the world like a butterfly, and do I need to talk about Disney?

So when I say I live on stories like the tiger in my favorite children’s book, Donald Bisset’s Talk With A Tiger (check it out, it’s so meta!) I think I also have to take into account the ways that storytelling isn’t a neutral act. Sometimes stories narrow our world. Sometimes they perpetuate really unhelpful beliefs: why shouldn’t Red Riding Hood be safe in her grandmother’s woods?

I have no good answers to this, but I turn to writers who have used fairy tales to make the world bigger: Natalia Theodoridou’s Sour Cherry is a Bluebeard retelling about abuse and liberation. He wrestles with the Bluebeard story by creating a world that is so big and lush and full of love, it can’t possibly be diminished. The ending of B. Pladek’s Dry Land is a description of a marsh that is so perfect, so lovingly rendered, that when the world ends, I’ll be able to visit it through the pages of the book. Lisel Mueller’s poem “Why We Tell Stories” lists all the reasons we tell stories, including want, and lack, and despair, and she ends it with this line: we will begin our story with the word and. I hope that stories, and climate fiction stories, are one of the places where we practice and, and that speculative fabulation allows us to imagine the world as it could be, to make more room in it, and share in our grief and joys.

What a Fish Looks Like places you in a growing tradition of queer writers thinking about climate. What links queerness to ecological writing? How can it challenge our cultural understanding of nature?

I want so badly to answer that every queer person was bitten by a radioactive spider and now we’re all climate change superheroes that meet other superheroes on rooftops to figure out how to take out oil pipelines and so you should absolutely read our fiction!

How about this: instead of a radioactive spider, maybe it begins for a lot of us the first time our natures, desires, and bodies conflict with the programming we are told is obligatory. We are, to borrow Addie Tsai’s title, Unwieldy Creatures, and if we’re queer, our bodies and desires tend to revolt early and often. If we were very very lucky, we were able to find moments of euphoria or belonging outdoors. Charlie J. Stephens’ book A Wounded Dear Leaps Highest describes this so beautifully. Sabrina Imbler’s How Far the Light Reaches is another example. I was so lucky to have the ocean. The ocean didn’t care about my gender expression or that I was in love with all my best friends. I felt like the ocean and I had a special bond, and so when I started seeing more and more plastic, more jellyfish out of season, I had a sense of climate change that was as embodied to me as my own dysphoria.

In lieu of swinging across rooftops or other superpowers, I also think there are frameworks the queer community can offer. I know this could sound trivializing, but I think queer loves, and queer breakups, have a lot to teach people about climate change. My book begins with Seb, who was in one of those queer relationships that wasn’t just about love, but about mutual becoming. When that relationship ended, Seb felt like their habitat had been destroyed, or like they’d gone extinct. They’d say things like “my world is over,” but queer communities don’t do endings. In queer communities, your ex is right there across the table from you painting banners. It’s a weird new world. It’s maybe not exactly the world that you wanted, but it’s strange and wonderful and continues. Yes the world has ended and everything is lost, no, we’re all still here, and we are responsible for every living thing at the party.

In The Future Is Disabled, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha talks about disability technology, as comprising not just all the technology we are lucky to have that evolved because of disability activism (like talk-to-text) but also the technology of community care, mutual aid, checking in on one another. I want to think that queerness—as it connects to other movements like disability justice, intersectional feminism, Indigenous movements, abolitionist and liberatory movements throughout history from Black Lives Matter to Free Palestine—all of these bring their own technology and frameworks. We need them all to trouble the traditional binaries of “will we survive,” or “will the meteor get us,” or “us” vs. “nature,” and ask: how could it look instead, how were we caring for one another, how were we celebrating our entanglement, when the world was ending, were we planting a tree? I am so very thankful for presses like Stelliform that hold space for these conversations, and for publications like Foreword for supporting indie presses. Thank you so much for letting me visit.

Luke Sutherland