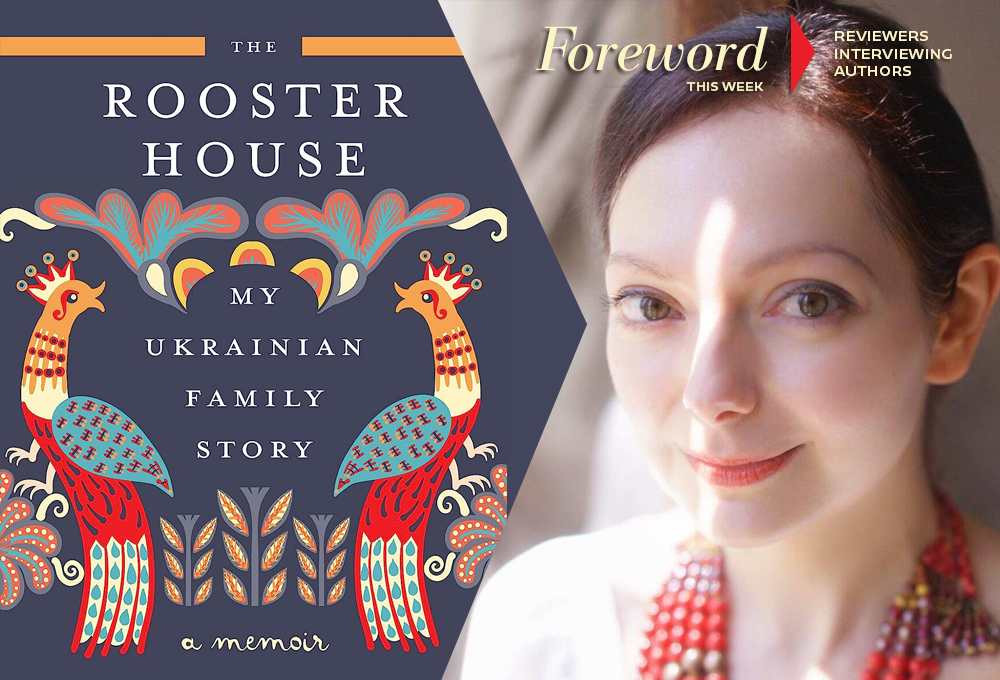

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Victoria Belim, Author of The Rooster House

A couple years ago we were smitten with An Atlas of Extinct Countries, Gideon Defoe’s “irreverent look at the history of defunct nations and the larger-than-life personalities behind them,” which earned a starred review from Eileen Gonzalez in Foreword.

But the Ukraine war has given us an all-too-real sense of how a nation might disappear, because Russia’s current plan is to take Ukraine by force, cow the Ukrainian people into submission, torture and kill any who resist, and rewrite the historical record to delete any mention of Ukraine’s history as an autonomous, democracy-loving nation.

The free world must not let this crime happen.

This week’s interview between Kristine Morris and Victoria Belim, author of The Rooster House: My Ukrainian Family Story, came together after Kristine returned her July/August Foreword review with a coveted star—tipping us off that this book and author deserved full FTW attention.

Helpfully, Kristine offered this brief introductory blurb:

Born in Ukraine, Victoria Belim moved to Chicago with her mother at the age of fifteen, and, as an adult moved to Brussels, a cosmopolitan city that provoked deep longing to reconnect to her place of birth. In 2014, despite Russia’s invasion of Crimea and mobilization of troops at the border, she decided to travel to Ukraine—wanting to feel connected to her family and national roots, but also to resolve a disturbing family mystery.

Please share some of your childhood memories of Ukraine and how these recollected images fueled your longing to belong to that land and people.

I lived in Ukraine until I was 15 and it shaped all my early childhood memories. Years later I can recall the exact scent of lilacs in my grandmother’s garden, the scent of her house, the shimmer of light on the surface of the river flowing past her house. I have always channeled these memories into creative work, using them to inspire my writing on scents, culture, books. It was the totality of these impressions that made me feel a strong connection to Ukraine while being outside of it.

The Rooster House tells of your discovery of a line in your great-grandfather’s journal relating that his brother, Nikodim, had “vanished in the 1930s fighting for a free Ukraine.” Nikodim was never seen, nor spoken of, again. Please tell our readers how finding that journal entry affected you, and what there was about the situation in Ukraine that made your family so secretive about Nikodim’s disappearance.

Old fears have deep roots. The past is never far behind in lands that many historians refer to as “the bloodlands.” Though the Soviet Union was long dead and the KGB was no more, the memories lingered. The fear persisted. It even continued living in me, someone who lived for most of her life outside of Ukraine and who had no experience with the Soviet secret police.

What is there about you that gave you the courage to travel to Ukraine during a time of escalating conflict with Russia?

A strong desire to be with my grandmother during this difficult time. A desire to learn the truth about our past.

Please describe the way you were received by family members and neighbors when you arrived at your grandmother’s house, their attitudes to the war, and, if you’ve had contact since then, what their situation is like now.

In the village, life is dictated by the land—planning, planting, harvesting. It was the same in 2014. When I arrived, everyone assumed that I came in spring to help my grandmother with the new planting season. The war remained in the background, not because everyone ignored it, but because there was no way to live otherwise.

At the time you wrote the book, you were in conflict with your uncle Vladimir, who surprised you with his negative views on Ukrainian nationhood, his defense of Stalin, and his longing for a return to the “glory days” of Russia. Have you found there to be many Ukrainian nationals who feel this way? If so, what reasons do they give for such desires? And for those who believe in Ukraine’s right to exist as a free, independent nation, how do they justify their belief knowing that Ukraine has been under occupation for so much of its history?

Polarized opinions exist in all countries, but in Ukraine, there is definitely an element of Soviet nostalgia. To be exact, Vladimir never longed to return to the glory days of Russia. He longed to return to the Soviet Union. We tend to conflate Russia and the USSR, but in reality, the difference is quite distinct. There are people who long for the USSR, but who have no interest in being part of Russia. There are those who see the destiny of Ukraine as part of Russia, but they are definitely a smaller group.

I don’t think that anyone needs to justify the right of Ukraine to exist, just like Greece or Bulgaria need not do so, despite the fact that they also have experienced long periods of occupation in their history.

The title of your book, The Rooster House, comes from the colloquial, and derogatory, term for the mystical sirens that decorate the doorway of the magnificent building in the central Ukrainian town of Poltava where you spent your summers as a child. The mansion had been a headquarters of Russia’s infamous KGB, and the building still holds memories for many—of torture, disappearance, and death. Still cloaked in an aura of fear, the Rooster House ended up being key to resolving the mystery of Nikodim’s disappearance. Please describe your search for answers, why your grandmother was so against it, how you were led to the Rooster House, and whether you came away with the truth or feel that pieces of the story are still missing.

When I first came to Ukraine, I believed that finding answers to the questions that haunted me was a matter of a few conversations with my grandmother and a few calls to the archives. I now realize how hopelessly naïve I was. The information I sought was in the grey zone of classified documents and finding it was complicated. What’s more, my grandmother refused to talk about the past, fearing it and fearing its effect on us. I had to overcome my own fears, which were remarkably strong. It was a long process of asking questions, traveling, meeting people and not giving up hope.

I sometimes think that I could continue my research to look for other parts of the story and other puzzles, but at this point, I’ve come to terms with the truth I discovered. I even overcame my fear of the Rooster House.

The city of your birth, Kyiv, was a meeting-place of many cultures, as was Ukraine itself. While you were growing up there, did you notice tension in your family or community between Russians and Ukrainians?

There was never any tension between Russians and Ukrainians during my childhood and certainly not in Kyiv. Marriages between Russians and Ukrainians were common in the USSR, as was demonstrated by my family.

You express deep admiration for Ukrainian culture, and the way its arts and crafts have survived the country’s tumultuous history. What is now being done in Ukraine to protect and preserve its monuments, artworks, and traditional crafts?

Russia has appropriated much of Ukrainian culture throughout its history, from baroque church architecture to cuisine. But a different logic exists in situations of war, and unfortunately art and culture suffer. Many artisans in Ukraine continue working, protecting their craft. That’s the only thing Ukraine can do at this point.

Please tell our readers about your writing process and how you were able to write such an intimate account of your love for Ukraine, of your family’s disturbing secret, and why this story is so important.

The process was specifically about telling my family’s stories, which is what inspired me. At home many stories are told about great-grandparents and we use them to face the difficulties of today. I wanted to remember these stories. Being able to hear the voices of those long departed made me able to write, even if at times it was difficult and painful.

Despite the gravity of the situation in Ukraine, your book, at the time you finished writing it, expressed hope for the survival of the country and its strong, resilient people. With the way things look now, do you still hold this hope? Why, or why not?

Yes, because one must remain hopeful. As my great-grandmother Asya used to say, “The human heart is a strange instrument. It gets used to pain and never ceases to hope.”

What do you do to stay positive when faced with current events?

Focus on work, writing, growing my little garden in Brussels. Unable to travel to Ukraine, I planted my favorite flowers that I remembered from my grandmother’s garden—marigolds, hollyhocks, cosmos, calendula. Every time I see a new blossom opening, I feel hopeful.

How has returning to the land of your birth, discovering the truth about Nikodim, and seeing how learning that truth brought healing to your family made a difference in your life?

It helped me understand our past and our history better. It helped me to come to terms with losses in my life and to develop new sources of resilience from within.

How might others searching for their Ukrainian roots proceed if travel to Ukraine is not an option?

Calling archives, getting in touch with community groups who help with finding relatives. I have to say that this is a difficult task, even if one is in Ukraine.

Please tell our readers about your work with Ukrainian refugees.

It’s a local Brussels initiative, organized by the local Ukrainian community to help people get settled.

Do you have plans for another book? If so, what might its topic be?

I am currently translating a novel by an Iranian author, Zahra Abdi. Then I will plan another book project.

Kristine Morris