Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Josephine Caminos Oria, Author of Sobremesa: A Memoir of Food and Love in Thirteen Courses—Part One

We sometimes think of our reviewers as explorers—this is your assignment, scribe, if you choose to accept it—venturing off into the uncharted stories and ideas of new books, logging details as the pages slip by, then posting an official communiqué in the form of a review.

Not that it’s dangerous, but on rare occasions the experience is life altering. The ever intrepid Kristine Morris just returned from such a place, where she encountered the Argentine notion of sobremesa under the guidance of Josephine Oria. Sobre what? you say, just like we did—but here’s where we step away and let Kristine engage Josephine in an extraordinary discussion.

As you’ll see below, they got along so well that we decided to break their conversation into two parts, with the second installment coming next Thursday.

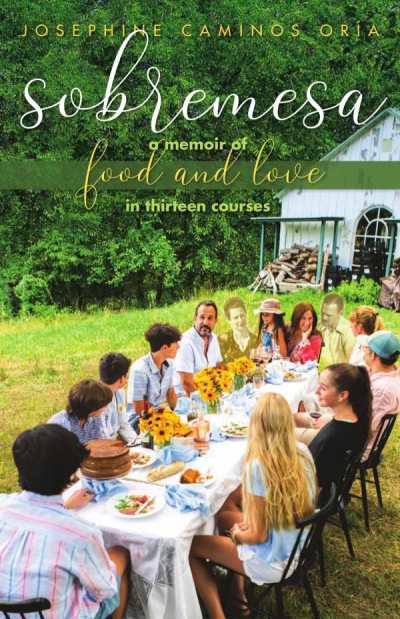

Sobremesa is a delightful account of growing up and finding your place in two different cultures, that of Argentina, where you were born and have extended family, and that of the United States, where you were raised. And it’s a love story, as well as a tale of family ties that encompass generations, even beyond death. Sobremesa is also a cookbook, one that invites us to enter the world of Argentine culture and cuisine, with stories that make us feel like part of your family. And the concept of sobremesa, a word that has no equivalent in English (time spent together at the table long after the food is gone is a very basic definition), expresses and perfectly ties together all the threads of your narrative.

Tell our readers about the Argentine sobremesa. Is the tradition still as strong today as it was for your parents and grandparents? What makes it so meaningful?

Gathering around a table and sharing meals has always been—and continues to be—the glue that connects most families together. Growing up in Pittsburgh, sobremesa, time spent at the table after the meal is done, surrounded by dirty plates and rumpled napkins, was non-negotiable at my parents’ table of eight (plus two for my abuelos, Alfredo and Dorita, when they visited from Argentina). Sobremesa helped me make sense of the world. It’s where we told our stories; where we had the real conversations; where the magic happened. If the conversation turned south, you’d buckle up and see it to the end. Then, before leaving the table, everyone would kiss and make up. Those tableside chats are forever etched into my heart and taste buds. They helped form me as the person and woman I am today. But above all, sobremesa was a means for my parents to pass on their Argentine traditions and culture beyond DNA. It satiated a hunger in me that food alone never could, tethering me to an Argentina that had always seemed worlds away. Through the years, this postprandial tradition has stayed with me, so much so that it became the evocative medium that allowed me to tell my story.

What drew you to write about the Argentine tradition of sobremesa?

It all began in 2017 on a hot July morning in Charleston, South Carolina. I was on a walk with my husband, Gastón, and my older brother when I received a “message” of sorts that I had to write a book about sobremesa. “Sobremesa? But why?” I thought to myself. It doesn’t even have an English translation. But the voice in my head insisted, telling me, “Because not enough people know about it, and they’re going to need it.”

Looking back now, it’s interesting—the timing of Sobremesa’s release, when we need it more than ever. Just over a year ago, words and concepts like coronavirus, social distancing, and stay-at-home orders were virtually unknown to the majority of us. But now, we must bravely hold onto hope, love, and most importantly, one another. We can’t put words to the fear, isolation, and loss—of loved ones, of jobs, of our homes, of our support systems—that we collectively awakened to each morning. That we still do, to this day. How better to explore and make sense of this new normal we are all navigating than at sobremesa? The down-time and connectivity it fosters is essential to both our humanity and our sanity. We are all craving to gather once again—to connect with others and make sense of our lives and the world around us. It’s what we do at the dinner table. Those who eat-and-run miss out.

Uninterrupted time at home with my family was one of the greatest gifts to come out of the last year. We sobremesa’d most evenings, blasting Pavarotti and Bocelli over the table. Introducing the kids to things we are passionate about. Then our kids would take over and introduce us to their music and likes. We talked about scary things, the unknown, the “what ifs.” We also laughed a lot. We told our kids about our own childhood shenanigans. Sure, they’d heard the stories before, and sure they’d get bored, but it helped us get through scary and trying times together.

Most mornings I’d awaken to piles of dirty dishes, but with a couple cups of yerba mate in my system, I’d roll up my sleeves and get to work. And as I washed the dishes, one by one, I’d start digesting last night’s tableside conversations and realize that the dirty dishes were worth it. My children are growing up way too fast. All of a sudden, I have an almost-eighteen-year-old! That downtime gave me time to get to know the free-thinking adults my children are on their way to becoming. It gave me time to tell them about my own views, and to reflect on how we had prioritized soccer and after-school activities over family time. To this day I feel that if we miss too many consecutive sobremesas, we start to slowly unravel, so I’ve chosen to prioritize it above many other things I previously thought we had to do. It isn’t always easy. Especially with four teenage boys and a nine-year-old daughter. Sometimes it takes grit and grace to stay at the table, next to a child who is asking, on repeat, “May I be excused? Now? Now?” I’d like to say we stay at sobremesa every evening—but packed schedules simply don’t allow it. We try to practice it at least every other day.

Your parents left Argentina in 1974 to settle in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They were in their late twenties and early thirties, with five small children. You were just a baby. That couldn’t have been easy for them. Why did they leave Argentina, and what drew them to Pittsburgh?

Coming to the States was a decision they made together. They were both chasing their dream of creating a better life for their family. My dad, a cardiologist, left Argentina because the military government at the time clipped his wings and there was more potential for his medical career in the US. It’s my understanding that the military had taken over the hospitals and placed their own men at the top. My father had originally been recruited by the Cleveland Clinic, but he first had to complete a residency in the US. He did this at the Western Pennsylvania Hospital. At the tail end of his residency, when the time was approaching to move on to Cleveland, my mother put her foot down and refused to leave Pittsburgh. She had found a community of like-minded Latinas—Peruvian, Cuban, Colombian, and Argentine—who eventually became our US family. (They also happened to be wives of doctors who spent hours on end at the hospital.)

My abuelos spent months upon months with us in the States, oftentimes sacrificing their own lives. I imagine my parents felt an immense amount of culture shock at the time, not to mention loneliness. My abuela Dorita maintained normalcy in our home by preparing the Argentine dishes my parents were raised on and pined for. It was her way of grounding our family so we could explore and identify with our new culture in the US outside of the home while still celebrating and escaping to our Argentine culture behind closed doors.

How did you benefit from growing up in a bi-cultural family with strong ties to both countries? What were some of the difficulties?

My parents pretty much lived their lives in Pittsburgh in the same manner they would have back in Argentina. So even though I came to the States as a baby, I began to navigate both cultures at home from as far back as I can remember. Experiencing and understanding different kinds of traditions, languages, and practices broadened my mind. I believe it made me more tolerant of different perspectives. It made me understand neither way was the “right” way. I also think it made me much more adventurous with food. Cooking in the kitchen with my Argentine abuela made me curious about trying different dishes.

But while I got to see first-hand that there are different ways to live, celebrate, and express oneself, there were many times growing up that I just wanted to blend in. Likely because of my own insecurities. My biggest takeaway of being raised bi-cultural is the tolerance and adaptability it taught me. Both are very important for developing and maintaining honest, healthy, and open relationships that thrive.

How did you cope with the feeling of being divided between two places, and belonging fully to neither?

In Pittsburgh, we were known as the family that spoke Spanish, and in Argentina I was known as la Yanqui whose Levi jeans hung a little too loose for their liking. Throughout my life, I always thoroughly enjoyed our travels and trips to Argentina. But as a teenager I suffered from “imposter syndrome” as I began to hang out with my Argentine cousins and their friends. They’d ask me about my accent, my clothes, etc. I felt that they saw me as American, not Argentine, and I got the feeling that I was not fully either culture. The challenge is finding that sweet spot in the middle. Meeting Gastón helped me find and embrace the Argentine in me.

You mention having felt an ever-deepening call to Argentina, despite your ties to the States. What was it about Argentina, or your image of it, that drew you to return?

My abuelos—Dorita and Alfredo—were anchors in my life. They tethered me to Argentina. They fed us enough stories about our faraway home that it instilled a deep sense of curiosity and love for the country. They were staunch nationalists, and more than anything wanted us to understand that no matter where we lived, we were cut from the same Argentina they loved with all their hearts.

I never imagined I would return to Argentina to live and work. And I never imagined that, after a week in Argentina with Gastón, I would be ready to leave my entire life in Pittsburgh behind to craft a new life and a future that I had never seen coming. I don’t quite know how to explain it, but I found something in Gastón akin to the feelings I had with my abuelos Alfredo and Dorita. I found my grown-up Argentina in him and have reveled in fully discovering and immersing myself in it ever since. If anything, I’ve since learned that home really is where the heart is—and that means wherever my husband and children are. Today, I joke that I am an Argentine girl who speaks Pittsburghese and thinks she’s Carolinian. (I moved to Charleston, SC, last year!) Still, as my abuela Dorita used to say, “You can take the girl out of Argentina, but you can’t take Argentina out of the girl.”

Please tell our readers about meeting Gastón. It was a bit complicated at first, wasn’t it?

Gastón and I met at a turbulent time in my life, on the heels of a devastating breakup that upended my world and led me, reluctantly, back to Argentina in my early 20s. It was a time in my life when I felt I was done with men altogether—that I didn’t want to cook for a man anymore, that I didn’t want to get dressed up for a man or wait around on a Saturday night for a man to finish up his golf game or whatever. We definitely clashed at first. I can say I didn’t hold back. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t concerned with what a man would think of me. I was genuinely myself. And at that moment, it wasn’t very pretty since I wasn’t in a great place.

Gastón took it in stride, and, you could say, dished it right back. I was surprised, to say the least. While we clashed, we also connected on a level I had never before felt with a man. He was able to rouse emotions in me that even my boyfriend of almost ten years couldn’t quite get to. It was certainly confusing. But I ended up falling hopelessly in love. His humor and general openness were what first drew me in. I like to refer to him as an uplifter. The rest is history. But I am forever grateful I ended up in his arms because they truly brought me home and helped me get to know another side of myself and of Argentine culture that I’m not sure I would ever have fully understood otherwise.

Having lived in both cultures, what do you think Argentine culture can teach North Americans, and what might Argentina learn from North American culture?

Both of my dual—and sometimes “dueling”— cultures have very wonderful traits that are near and dear to me. The thing that sticks out most in my mind about my North American friends and family, neighbors, and colleagues is how, at the first sign of a disaster or tragedy, the surrounding community will rise up to help in many ways—whether it’s starting a Go Fund Me, months of meals, carpooling your children, even cutting your grass without your asking. Casseroles are left on your doorstep with love. North Americans feel an immense sense of loyalty to their community and are an incredible example of compassion and generosity of spirit.

The thing that strikes me most about Argentines is their candor—once you get used to it, it’s incredibly freeing and refreshing. I believe it creates more intimacy. In the US, while our politeness and extreme political correctness is a virtue, it can also build walls around us that make it hard for people to get to know the real person behind the façade. Also, Argentines have an uncanny ability to focus on the now, and not look to or worry about the future too much. I believe this is somewhat a result of years of political unrest and economic highs and lows. I realize that’s quite a blanket statement, and it may not pertain to everyone, but generally Argentines enjoy and embrace the present more than the average person in the US, me included. Their longstanding sobremesa tradition is a reminder that life is meant to be savored and enjoyed now—daily, not just on special occasions.

Now has taken on a whole new meaning for all of us, hasn’t it? If coronavirus has taught us anything, it’s that the time is now to make a change—to slow down and stop putting off the important things and people until tomorrow—because, as we’ve all been abruptly reminded, it’s not promised. My wish this year is that we all embrace the slower lifestyle Argentines have enjoyed for years on end, and that we make it back to the table with the people we love, and those we are meant to love—even if we don’t yet know it.

What does the conflict over immigration say to you about people’s attitudes toward cultural, racial, and ethnic differences? Do you think Argentina would respond in a similar fashion as the US has to immigrants seeking to enter their country?

Both Argentina and the US were built on immigrants. We should never forget where we came from. Like the US, Argentina has historically had—and currently has—an influx of immigrants coming from neighboring countries where they are living in poverty. For example, I have read that in Argentina, average laborers are paid something like three times as much as they would be paid in Bolivia. I can’t opine personally about Argentina’s response, but I can say that there is a saying in Argentina: “Donde comen dos, comen tres.” (Meaning, “where two eat, there is always room for a third.”)

Sobremesa doesn’t discriminate. Everyone is invited to the communal table. Its message of diplomacy could be a small yet effective step towards a cure to what divides us as a nation, and on a global scale, right now.

Kristine Morris