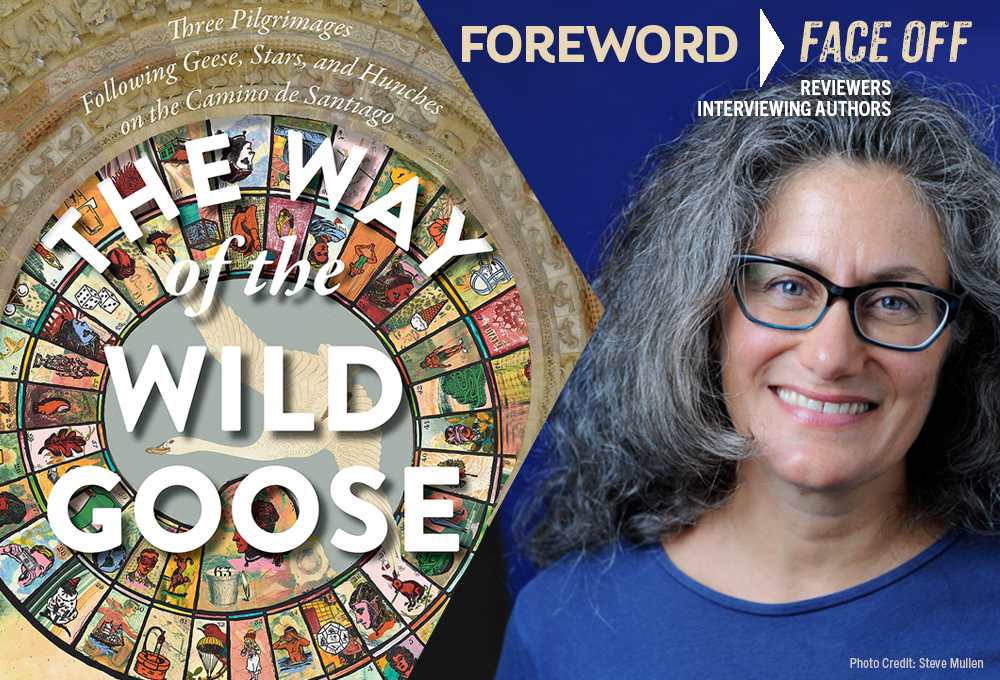

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Beebe Bahrami, Author of The Way of the Wild Goose: Three Pilgrimages Following Geese, Stars, and Hunches on the Camino De Santiago

The recent bombshell report detailing decades of sex abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention is nearly a copycat to the many lurid investigations into the Catholic Church. The abuse and subsequent coverup by the leadership of both churches is so carefully choreographed as to be part of Christian liturgy.

In our disgust, what we mostly take note of is the fact that these institutions are run by men—the culmination of a two thousand year experiment in patriarchy. It wasn’t always such. Once upon a time, matriarchal, pagan systems of belief connected Earth with heaven, and goddesses spent as much time amongst us in nature as they did up above.

This week, we implore you to spend a few minutes reading the following conversation between Kristine Morris and Beebe Bahrami, wherein they discuss Beebe’s The Way of the Wild Goose and her dreams for restoring women to their rightful place at the center of family, nation, religion, and keeper of the Earth.

The Way of the Wild Goose makes walking the iconic pilgrim’s trail, the Camino de Santiago, a lively, visceral experience for the reader. It’s a compelling, generous book that reveals how the Camino can strip away anything inauthentic and bring its walkers face-to-face with their own truth. What, for you, was the greatest gift of the Camino, and how has it affected the way you live today?

Most broadly speaking, the greatest gift of the Camino to me has been my whole way of life as a writer devoted to the trail and its legacy in Europe. Beyond this professional grace, it has given me so much that has made me a better person and enriched my life. Top among these gifts is how it simplifies everything to the basics and teaches that we need very little materially. I focus less on stuff and more on others, nature, and my inner life. It has taught self-reliance and shown me my strengths and vulnerabilities, and that these shift and evolve as we grow older, especially if I keep walking and seeking. It has taught me how important authentic and rich connections are, to others and to the earth. It has taught me to be present and to enjoy life on a daily, moment to moment basis. It has taught me that every day I need to connect to and care for where I live, both community and wild earth.

What is there about you, your background, education, and heritage that inspires your travels and your writing?

I come from a wonderfully diverse family and was born and raised in a progressive, Earth-forward town in Colorado—all influences that have made me curious about the world, comfortable in it wherever I go, and deeply devoted to honoring and keeping our planet and environment healthy. My upbringing also exposed me to many religious and spiritual outlooks, and there was always some form of mystical poetry being recited or music being played daily in our home, which opened me more to the depths of the human spirit and the richness of our world.

The Camino’s demand that we live simply can show us how fear, lack of trust, and excessive concern for little things can burden us. I loved how your irritation with your heavy backpack led to the realization that “the heaviest item in my pack was a tight and dense bundle of fear that had made me pack things I might need just in case.” Has this realization made you embrace a degree of minimalism in your daily life? How has the Camino affected your concept of what is needed for a “good life?”

I walk and bike most places. My husband and I have one car and it’s used only when footing or pedaling aren’t practical. I tend to question nearly every purchase, and if it isn’t essential, doesn’t give some real value to everyday life, or doesn’t give back to its makers and show sustainable values, I don’t buy it. I recycle, compost, and reuse. I pick up trash almost every day. I seek active entertainment: reading, writing, playing music. I love gathering with close friends and family for home-cooked dinners. I commit to physical and mental well-being and take a daily long walk or go for a jog or surf session, and also do 30-40 minutes of yoga. The Camino has also taught me that we really feel fulfilled when we are engaged and connected to each other, and I like to listen to the stories others have to share. I also pay much more attention to the stories that Earth herself has to tell.

What does “pilgrimage” mean to you? How does it differ from other types of walking tours, hikes, or treks? To what extent do you feel that you are a pilgrim, whether on or off the trail?

To me, a pilgrimage is setting off toward a holy goal, whether it is a destination or the path itself, seeking to transform oneself (and the world) for the better. When I am open to life and what is before me, seeking to grow, I feel I am a pilgrim, but I hesitate to join in the often-engaged Camino conversation about what it is to be a pilgrim, or who is a “true pilgrim.” I think that, at its root, being a pilgrim means seeking to grow and expand by stepping out of familiar routines and into the unknown while simplifying everything down to the basics: walking, eating, drinking, and sleeping. And trusting—what might be called having faith—that all that you need (not want—hat tip to the Rolling Stones) will be provided as you go.

In the case of someone who is not traditionally religious, what might turn a hike into a pilgrimage?

A hike becomes a pilgrimage when you focus on whatever is holy to you. Many hikers are lovers of nature, and that to me is holy; when that hike becomes focused on letting go of everything but the beauty and the possibilities before one, that feels to me like a pilgrimage.

Please describe the term “trail magic,” and tell our readers how it manifested for you as you walked the Camino.

Trail magic is unexpected things happening with perfect timing to address a need or hope. Maybe you are hot, tired, and out of water or food, or maybe you keep worrying about someone in your life, and you turn a corner and there is a person—it could be a local or another pilgrim—who offers you exactly what you need before you even ask. And sometimes trail magic isn’t a person, but a table in the middle of nowhere with a basket of food, a jug of water, and a sign telling you to help yourself. It could also be a sign that only you will recognize, that gives you the answer to the worry or issue tumbling about in your mind in that moment. It could come in the form of a billboard, a church engraving, a hand-written message on a rock or wall, or the sudden appearance of a bird or other animal that means something profound to you. Attached to trail magic are trail angels—Appalachian Trail hikers will also recognize them—those folks who appear at the right time to offer help, be it a lift, food, drink, or words of wisdom.

Trail magic manifests all the time, each day I have ever walked, on each Camino. Maybe it’s because when I walk, I am taking more time and making an effort to be present. What if we did that every day in our ordinary lives? I bet we would experience trail magic, and meet more angels, too. At its root, trail magic is synchronicity, and synchronicity—making connections to that which is already around you—increases with presence and awareness.

All this said, there still is a magical element to it on the Camino. How did that local know what I needed just then and step forward to offer it without my asking?

Your book shares your fascination with the matriarchal, pagan cultures that pre-dated Christianity in Europe before a fierce patriarchy nearly obliterated them. What do you feel Western civilization lost with the imposition of a patriarchal worldview? Do you see a way to bring what was good about this earlier worldview to bear on world events today? Why or why not?

The patriarchal worldview has severed humans from nature, the planet, even our own bodies. It severed Earth from sky, placing a god up there where all things are good and us down here where all things are blemished. It changed our relationship to the Earth, which became no longer a “thou,” but an “it,” and it did the same to human relationships. It made everything, be it land, women, or children a potential possession, since patriarchy depends on a patriarch and he depends on sure paternity. Everything—land, materials, bodies (human, animal, and plant), and labor became an object, a potential commodity, and not a being.

Patriarchal systems are not only unjust and immoral, they knocked our world into imbalance, destruction, greed, and ruin. If we reclaim and reconnect to ourselves—our bodies, souls, minds, and our planet—and let the gods walk down here as much as up there, and show all life reverence and respect, we can achieve greater balance and can steer ourselves away from devastation and destruction. I actually think there are many people striving to restore reverence and balance in all things. Their loud voices and anger right now may be a sign that their numbers are growing and patriarchy is crumbling and losing its entitlement to do whatever it pleases without care for others or the planet.

How are hints of early matriarchal cultures still seen in the daily lives of people along the Camino route today?

They are visible especially if one spends enough time in the northern villages where there are many women-run and -owned businesses compared to farther south. The smaller sustainable family-run farms of the north also give evidence of women’s influence, compared to the larger latifundia-style farms in the south. But perhaps the most obvious hint of the survival of earlier matriarchy is the devotion to Mother Mary. One sees this far more than one sees devotion to Jesus or Saint James, to whom the Camino is devoted. This devotion to Mary is present everywhere in Iberia and France, but the way it expresses itself in southwestern France and northern Spain is special: there, Mother Mary is more present than any other holy personage, and most of the shrines devoted to her have origin stories based in nature—someone found an image of Mary floating down the river, in a dolmen, on the hilltop, in a tree trunk, emerging from a spring, in a cave … and built a chapel there or near there, with the image installed on the altar.

Why are the places that are felt to be holy marked by the sign of a goose, or a three-pronged symbol for the foot of a goose? What is there that made the goose an appropriate symbol of the divine feminine, now in hiding, but ever alive?

The goose and the goose footprint, that three-pronged trinity of the cycle of life—maid/mother/wise woman, birth/death/rebirth—is the symbol of old native European goddesses that many folklorists began to notice and document, from Jacob Grimm to Charles Perrault, who named his folktales, not by coincidence, Contes de ma mère l’Oye (Stories of my Mother the Goose). Most recently, French medievalist Philippe Walter has written quite extensively about this connection, suggesting that Mother Goose is none other than the ancient mother goddess.

There are many ancient references to this connection between waterfowl and European, Near Eastern, and Asian goddesses. Numerous ancient Greek paintings depict both Aphrodite and Artemis with geese, and the Norse goddess Freya is associated with swans. The sacred animals of the Roman goddess Juno are geese. The German goddess Perchta, who has goose feet, appears also in southern France as Bertha, also known as La Reine Pédauque, the goose-footed queen. Bronze offerings found in Gallic Iron Age sites over 2,000 years old also reveal the presence of geese, such as the image of the goddess of the Seine, Sequana, discovered in Burgundy, depicting a woman standing in a duck-shaped boat, or the discovery of a local Breton goddess at Dinéault, in Brittany, who has the image of a goose in strike pose on her helmet.

And then there are the many folktales across southern France and northern Spain with hybrid divine female characters—now called fairies, they were once nature goddesses—who have animal features. Among the most common are women with bird feet and women with snake bodies. For ancient people who lived close to the land, birds and snakes take on transformative powers: both disappear and reappear with the seasons, both molt/shed, both lay eggs, both possess uncanny skills and magical powers over Earth and sky. In sacred art across the world, birds and snakes are the most depicted as representing connections to the divine and symbols of reincarnation, resurrection, rebirth, regeneration, fertility, and the ability to connect heaven and Earth, whether as messengers or as gods/goddesses in their own rights.

As patriarchal outlooks slowly dominated these Earth-bound systems, these powerful Earth divinities went underground, so to speak, and held on as fairies in fairytales, which were not just stories to entertain, but a means of teaching and passing on the Earth-bound wisdom that was being marginalized. It was a quiet, powerful, and gentle way to survive and continue teaching Earth science and Earth morality.

The Way of the Goose presents the wholesome, kindly, welcoming faces of the people you met along the Camino. Was there ever a time when you felt afraid? Please describe the event and how you resolved it. If not, what allowed you to feel safe and secure as a woman walking alone?

In general, the cultures and lands where the Camino passes are very safe. I gained confidence as a female trekker through decades of hiking the many pilgrim trails and tributary paths in northern Spain and southern France. But no matter where one walks, at home or anywhere else in the world, one should always be alert and keep one’s street smarts engaged. I do this, but find I have far more ease and access when I hike on the Camino than at home.

Still, that doesn’t mean it’s all perfect. There was one time, which I recount in the book, where I felt ill intent on the part of another, but it was quickly resolved by my walking crisply away (with eyes open in the back of my head), keeping alert, and being ready to call for help. But here is where trail magic arrived: another pilgrim far behind me had seen the exchange from a distance. He felt that something wasn’t right, so he sped up to walk with me.

I feel incredibly safe walking these trails, even with their growing popularity in recent years, because the people of the trail are still kind and generous, and it’s part of the culture to look out for each other’s well-being, pilgrims and locals alike.

What aspects of your writing bring you the most satisfaction?

All of them—I absolutely love every aspect of writing and being a writer, even the really hard stuff. Perhaps though, at the very top is that the only way to discover something at its root is to dive in, research, and begin writing about it to find out what is going on and what it’s all about. It is a road of adventure and discovery with surprise endings: I never really know what something is about until I commit to writing about it and only then, once a lot of ink has hit the page, does the topic reveal its deeper layers. Writing is like getting scuba diving equipment and training and diving under the surface to discover the many deeper layers beneath the appearance of things.

What is it about solo travel that makes it so rewarding? Given the state of the world today, would you advise other women to walk the Camino alone? Why or why not?

As a professional travel writer, I have discovered that better stories find me when I am traveling solo. There’s less of a barrier between me and the culture I’m in. Solo travel allows me to explore a place freely, and to discover what’s inside me and what I’m made of as I solve problems and make decisions each day. This often is where some of the best stories, or most surprising bits of local knowledge and information, are found.

I wholeheartedly recommend that women walk the Camino alone. I still find that the Camino is very safe. In many ways, it is likely far safer than the places we call home. It is very empowering to walk alone and to discover that you really can do it, learn more about your strengths and vulnerabilities (which sometimes turn out to be strengths!), and also make first-hand discoveries about the world. But as noted above, we should always remain aware and alert no matter where we are, whether back at home or out on the trail.

As a travel writer who spends time in different locations each year, is there a special place that feels most like home to you? Where is this place, and what is there about it that holds the essence of “home” for you?

I love my birthplace in Colorado, but I also seek to be at home wherever I am and to find the beauty and gifts that each place and its people offer. I have found that I feel most at home in those lands where the core Camino routes run—especially southwestern France and northern Spain. I especially love to make my homebase in Sarlat-la-Canéda in the Dordogne; each time I arrive there I have a joyous experience of deep homecoming.

This sense of home comes from the culture’s deep connection to the land and knowledge of the Earth, its openness to others and the interest in diversity exhibited by the area’s people, and the fact that these are incredibly compelling and ancient places with rich prehistory, legends and lore, cultural traditions, beautiful and protected nature, and warm and strong community-oriented outlooks.

I write about this in The Way of the Wild Goose and go especially deeply into the idea of home and finding home in my earlier travel memoir, Café Oc—A Nomad’s Tales of Magic, Mystery, and Finding Home in the Dordogne of Southwestern France.

What might today’s women do in order to imbue the world with the divine feminine? What might be the effects of such a change, given the current state of the world?

Not just women, but men, too, as we are all a mix of male and female. We can all be inclusive and celebratory, not just of the feminine and masculine in others but within ourselves. We can stop being binary and start being inclusive and weaving ourselves back into wholes again. We can reverently weave ourselves and Earth back into sacred connection. We can cherish the Earth as much as we cherish our children and work for greater security and beauty for the present and the future. We can also stand up to injustice and not let power-mongering bullies continue to cut up Earth’s body as well as our societies and communities. We can simplify our lives and live more lightly on the planet. We can spend more time walking, listening, and sharing our stories without assumptions. If we really listen to each other, we will find marvelous complexities, satisfaction, and healing. If we each heal ourselves, we heal each other and the planet. If I have learned anything from the ancient goose goddess and her folktales, it’s that we need to embrace wholeness and balance in ourselves, each other, and the Earth.

How would you describe yourself pre- and post-Camino?

Since I have been devoted to the Camino now for nearly three decades and I am always somehow on the Camino, I feel I am a perpetual constant work in progress, courtesy of the Camino’s magical ability to transform. In that sense, the Camino keeps me honest about what matters to myself, others, and the world.

The Camino has taught me that I need very little stuff, and that connection to others and devotion to and stewardship of the Earth are not only high priorities, but feel great. I keep my life simple and consume as little as possible; instead, I prefer to seek widening and deepening experiences in my work, with others, and in nature. I also now know that if I need to resolve something, I can go for a walk, and by the time I return home I will have a better perspective and, almost always, a solution.

I think I am also more chill. I have more trust in life and in myself. I have more patience. I know things are resolvable. It helps to have that constant healing force—feet to the Earth—to keep this perspective and to keep me grounded. I also find I am less timid about speaking up about what I experience on the Camino: that Earth is holy and beautiful, and we are all holy and beautiful; let’s celebrate and cherish this.

What do you hope readers will come to know as a result of immersing themselves in your book?

I hope readers will come to know many magical things, but top among them is that we and our Earth are amazing and beautiful and complex, and that it is incredibly rewarding to explore one’s inner and outer landscapes with a sense of adventure. I also hope readers will see how interconnected we all are and how our health, as individuals, as communities, as ecosystems, is dependent on seeing this interconnectedness and striving toward balance and reverence for life, each other, and the planet. I hope that readers will also come to know that there is magic, real magic, that sets into motion when we step onto a path of discovery, openness, curiosity, and hope—and that it can happen as much on a neighborhood trail at home as on the Camino.

Are you working on another book? If so, what is its topic, and why did you choose it?

I am working on another book, another travel narrative set in southwestern France and northern Spain. I am also trying my hand at a novel, a work of magical realism. For both, it is still too early to say too much more.

Check out our Petit Foreword videos with Margaret Renkl, André Alexis, Richard Dawkins, and many other talented writers conversing with our top editors, Michelle Anne Schingler and Danielle Ballantyne: https://www.youtube.com/c/Forewordreviews

Kristine Morris