Reviewer Kristen Rabe Interviews Josh Jackson, Author of The Enduring Wild

“BLM lands cover vast, varied ecosystems—from high deserts to alpine meadows—and many of them remain relatively undeveloped. This makes them critical habitat for native plants and wildlife, including threatened species. Because these landscapes are often adjacent to or between other public lands, they serve as migration corridors and climate refugia. Protecting and restoring BLM lands helps preserve biodiversity, safeguard watersheds, and build climate resilience across the West.’’ —Josh Jackson

We’re going to take you down a little rabbit hole in Utah to give you some backstory about a powerful man who despises the fact that officials in Washington, DC, manage large parts of his state. Which parts? Bureau of Land Management, US Forest Service, and national monument land. That guy is Senator Mike Lee—he’d like to see much of that property sold off to developers, many of whom are campaign donors, unsurprisingly.

To that end, in 2017, Lee helped convince President Trump to eliminate protections in Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments, and then, in 2018, he introduced legislation to bar any national monument designations in Utah altogether. Thankfully, it didn’t pass.

Let’s jump forward to the past month or so when long-game Lee’s name has been in the news again as part of negotiations over Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill. But he’s far more dangerous now because his Republican colleagues recently appointed him chairman of the Senate Energy and National Resources Committee, which has jurisdiction over the nation’s fisheries and wildlife, land grants, national parks, forest reserves, international fishing agreements, as well as the US Geological Survey and the Department of Energy.

In May, Lee introduced legislation during the Senate’s reconciliation bill negotiations that would make the Forest Service and BLM sell 3.3 million acres of land and also require those two agencies to make another 250 million acres eligible for sale. Thankfully, the Senate parliamentarian ruled against Lee’s proposal. Undaunted, he scaled it back to exempt national forest land but still force the BLM in eleven western states to sell upwards of 1.2 million acres near population centers, ostensibly to help with affordable housing. Under extreme pressure from Democrats and Republicans during final negotiations on the Beautiful Bill, he pulled the provision on Saturday night.

But the man from Utah is far from done—everyone with a love for public land and open spaces should strive to be as vigilant as today’s special guest, Josh Jackson, the author of The Enduring Wild.

If you’re on a search for more great Ecology & Environment projects, check out these four grand champions from the 2024 INDIES: A Global Warming Primer (gold), Life after Dead Pool (silver), Radical Adaptation (bronze), The Blue Plate (honorable mention). Digital subscriptions to Foreword Reviews are free.

In this book, you explore the remote, unexpected places managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in California. When did you start this quest? What obstacles did you face?

My obsession with BLM land began in 2015 during a camping trip to the Trona Pinnacles with my kids. Even as an avid hiker and camper, I knew little about the 245 million acres managed by the BLM across the West. That trip changed everything.

I started reading, researching, and learning as much as I could, only to find that most of the information was rather dry. Images of the landscapes either didn’t exist or were hopelessly outdated. So, I decided to see as many of these BLM-managed landscapes in California as I could, all 15 million acres of them. What kind of scenery and stories did they hold? The quest itself quickly became the biggest obstacle. How do you even begin to visit every accessible acre in a state as vast as California? A large-scale BLM map hangs in my home, and in those early months, I’d stare at it with overwhelmed eyes, wondering if it was even possible. As it turns out, it was—taking one two-day, three-day, or five-day trip at a time.

Which locations most impressed or surprised you?

The most surprising was BLM land along the Pit River in far northeast California. The river winds through a striking volcanic landscape shaped by ancient lava flows and the geologic upheaval of the Modoc Plateau. Towering basalt cliffs and rugged lava beds define much of the terrain. I had no expectations going in, but I was mesmerized.

The landscape that impressed me most was the Bodie Hills, a high-altitude sea of sagebrush along the Nevada border, just north of Mono Lake in the Eastern Sierra. With pronghorn, bi-state sage grouse, aspen groves, and peaks topping 10,000 feet, the place feels wild and alive. Of all the BLM lands in California, the Bodie Hills are the ones I return to most.

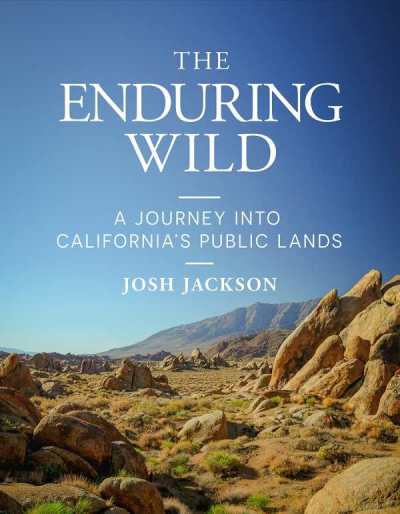

Your photographs are fantastic. What were you trying to communicate through these images?

Thank you! I was trying to convey two things. First, these landscapes are overflowing with scenic beauty and biodiversity—and they extend an open invitation to all of us. I wanted people to see the photos and imagine themselves there, to feel that these places are accessible and welcoming. Second, I wanted to highlight the quieter details that make these lands so special. Yes, there are dramatic mountains and rivers, but there are also boulder fields, quiet creeks, and grasslands that shelter endangered species. I wanted to tell their story, too.

What do you mean when you write about “place attachment”? What role does public land play in fostering connections?

In environmental psychology, place attachment refers to the idea that people who form strong emotional connections to a place experience a deeper sense of identity, belonging, and well-being. In the book, I argue that this connection to nature is essential—not just for our well-being, but for the survival of BLM lands.

Unlike our national parks, which have a built-in constituency, BLM lands have a kind of anonymity — overlooked, misunderstood, and often treated as expendable. Their lack of visibility makes them easy targets for mining, drilling, and efforts to strip them of protections. I kept returning to Baba Dioum’s words: “In the end, we will conserve only what we love.” But how can we expect people to love and protect places they don’t have a connection with?

The Enduring Wild is my attempt to introduce people to these landscapes—through stories and photographs—and to encourage them to go see for themselves. These places need more advocates. Connection is where that advocacy begins.

As you note, BLM manages 245 million acres across the western US and Alaska. What are your suggestions for adventurers who want to explore BLM land outside of California?

I suggest starting with areas that offer easier access, like National Monuments or National Recreation Areas. These places usually have established trails and campgrounds. Most are well-documented on the BLM website, which has detailed recreation pages for each western state. You can also reach out to local BLM field offices or connect with nonprofit “Friends of” groups, which often offer events, hikes, and valuable resources to help you get oriented.

What do you mean when you describe BLM land as the “cogs and wheels” of modern conservation? How does BLM land help preserve biodiversity, mitigate the effects of climate change, and advance other environmental goals?

When I describe BLM land as the “cogs and wheels” of modern conservation, I’m echoing Aldo Leopold’s idea that conservation can’t just focus on the iconic showpieces like national parks. BLM landscapes may be less celebrated, but they’re essential, working parts that keep the whole system running.

BLM lands cover vast, varied ecosystems—from high deserts to alpine meadows—and many of them remain relatively undeveloped. This makes them critical habitat for native plants and wildlife, including threatened species. Because these landscapes are often adjacent to or between other public lands, they serve as migration corridors and climate refugia. Protecting and restoring BLM lands helps preserve biodiversity, safeguard watersheds, and build climate resilience across the West.

How have conservation challenges intensified?

BLM lands are facing unprecedented threats. There are ongoing efforts to defund public land agencies, reduce staffing, rescind monuments, roll back key environmental protections, and even sell off hundreds of thousands of acres to the highest bidder. From the beginning, these lands were treated as the “leftovers” of the federal estate—and in many ways, they’ve always been under attack. And yet, they have endured: the great underdog story of our public lands.

They are essential—for our wellbeing as well as for the embrace they offer to the animal and plant kingdoms. In a world besieged by dissension, they are refuges of sanity and solace, where present and future generations can find common ground, where our kids can feel the earth, watch the moon rise, and come home with stories to tell.

I named the book The Enduring Wild to reflect that resilience. I hope it brings more visibility to these places—not just their beauty, but their deep ecological and cultural importance—and inspires more people to stand up for their protection.

Kristen Rabe