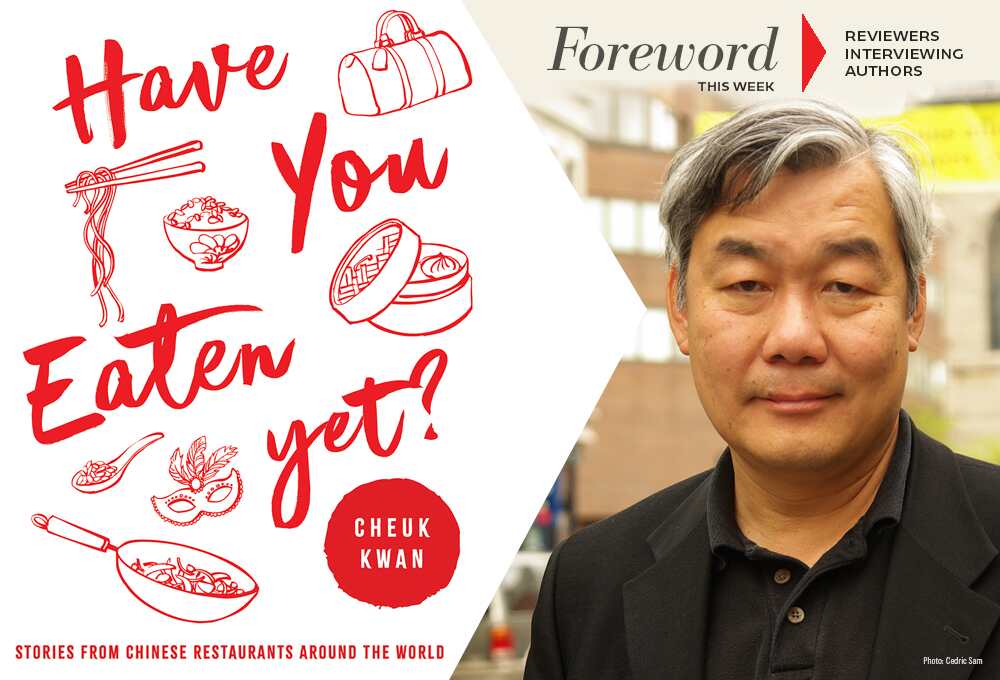

Reviewer Karen Rigby Interviews Cheuk Kwan, Author of Have You Eaten Yet?

This week—ideally, you’re reading this during your lunch hour—we’re ecstatic to feature intrepid filmmaker and food writer Cheuk Kwan, and to celebrate the recent release of Have You Eaten Yet?, his “fascinating, inquisitive global search for Chinese tastes that evoke home in any corner of the world,” according to Karen Rigby in her review for the January/February 2023 issue of Foreword.

In about the same time as it takes to down a single wonton, Karen responded with “absolutely” when we pitched an interview with Cheuk.

Enjoy!

Have You Eaten Yet? draws from locales in your Chinese Restaurants documentary series. What challenges or fresh perspectives did writing about them, versus filming them, present? Do you find moments that translate more or less easily onto the page?

I am more reflective and insightful revisiting these locales and events today than when I was putting the film together twenty years ago. We are dealing with two very different media here. A book provides more storytelling depth, as well as a more immersive and expansive look at the sociopolitical and ethnocultural issues I was covering.

Translating from the visual medium onto the page was relatively easy because the hardest part of the process—that of writing the story—has already been done. However, a book chapter allows me a lot more room for interiority and incorporating my life story into the narrative than a film episode can.

When you take many roles—interviewer, witness, foodie, traveler, friend, filmmaker—how do you decide when a moment is best left off-camera, off-page, and when it is vital to get at the truth of what’s unfolding before you? It seems like a delicate balance, being entrusted with people’s stories, and yet, looking at those stories from both a human and artistic perspective.

That’s what storytelling is all about: how do you grab the essence of the story from hours and hours of transcripts and footage and then rendering it into an art form. It certainly helps that, as a member of the Chinese diaspora, I am well acquainted with many aspects of our food, culture, and history, as well as our fears and aspirations.

I played all these roles as you suggested. But first and foremost, I try to be a friend to get them to trust me with their life stories. I spent a lot of time warming them up, getting the relationship just right. In a sense, I was breaking all the rules of documentary filmmaking; you know, the one about maintaining an objective distance from your subjects. I became quite involved.

Conversations about the Chinese diaspora often surround resilience, adaptation, and ingenuity. Were there aspects about this topic that surprised you by the end of your travels that you hadn’t anticipated?

There is always an element of delightful surprise. Take Norway for example. I’ve never met these people before I landed in the Arctic with my camera. And for a while, I thought “Oh, this is going to be a Nordic bore.” Certainly not as interesting as Madagascar. But I managed to tease out many elements of their lives and ended up telling a quasi-gangster story. That’s why the chapter in my book is called “Like a John Woo Movie.”

But mostly, I was totally in awe with vivid first-hand accounts of their courage and resiliency. It was a privilege to relive with my storytellers what they’ve gone through—the teenaged couple who escaped China by swimming for five hours to Hong Kong; the Christian evangelist who fled Vietnam as “boat people” and eventually landed in Israel; and the Muslim Chinese family who walked across the Himalayas to refugee camps in Pakistan.

In the book, restaurants are more than restaurants. They’re also community centers, microcosms. Why do Chinese-run establishments seem especially adept at gathering people?

These restaurants are often run like a family affair, so there’s that informal ambience that people like to hang out in. It doesn’t matter if you only drop by for coffee and apple pie in these Chinese cafés, you are always welcome and treated as part of the family.

In practical terms, Chinese restaurants are often opened longer and cater to what the customers want. There’s this thing about Jewish people eating Chinese on Christmas Day. Why? Because these are the only restaurants opened.

I’m intrigued by many of the stories that include women chefs. Could you tell us a little more about your encounters in Mauritius and Madagascar?

I made a point of seeking women chefs out just because they are so unusual in this business. These women started businesses on their own or took over the restaurant after their spouse died. They challenge stereotypes and confront systemic discrimination, and are stronger because of that. I am full of admiration for them and really enjoyed talking to them.

After having lived under an abusive mother-in-law, Colette moved out of the family home and started one of the most successful restaurants in Mauritius serving up a hybrid of her native Hakka and local Creole cuisines. Born in Madagascar, Miday had never been to Hong Kong or China yet she picked up what she needed from a Hong Kong cooking magazine to run a Cantonese seafood restaurant that would be the envy of everyone in Hong Kong.

Authentic or fusion, Chinese food is regional and different everywhere, but is there an essence or ethos that you feel ties it together? What makes a dish distinctly Chinese?

This is a hard question to answer. In my book, I mentioned that there are fifty-five ethnic groups in China each with its own distinctive cuisine, not to mention regional variations within the majority Han Chinese, which comprises ninety-two percent of China’s population.

But if I have to point to something, it’s the way Chinese treat their food. For them, eating is very much the essence of life and an important part of one’s well-being. There’s a whole consideration for the yin-and-yang balance of what you eat; that holistic way to look at food and health; and the communal way food is consumed. That’s why “Have you eaten yet?” became a colloquial greeting meaning “How are you?”

You’ve dined in remote corners and cosmopolitan cities. What’s your advice for travelers looking for great food off the beaten path or menu?

Be adventurous, be open. Look at what others are eating around you.

Do you have any traditions or new culinary adventures in mind for the New Year?

These days I retreat more to my comfort food, the Cantonese classics. It’s all there: the freshness of the ingredients, the subtlety of seasoning, and the inventive way different animal parts are used. I may be biased here, but when Cantonese food is done well, they are out of this world.

Karen Rigby