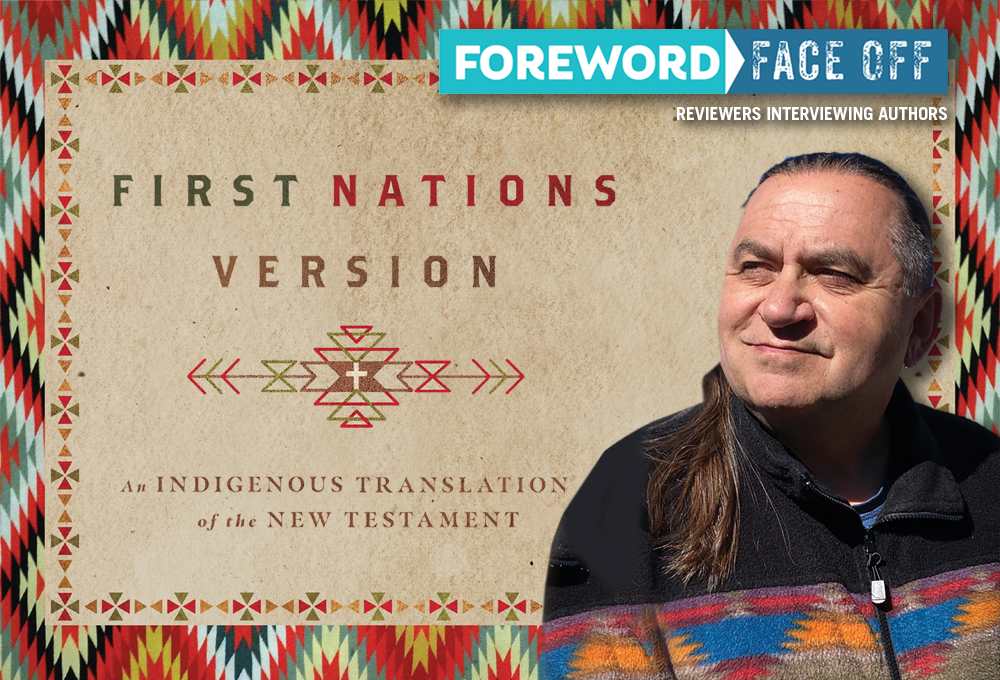

Reviewer Jeremiah Rood Interviews Terry Wildman, Translator of First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament

Upon hearing the great good news of the recent release of First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament, we rejoiced for the six million English-speaking indigenous people of North America who now have a Bible that embraces their tradition of oral storytelling.

With the help of InterVarsity Press, we connected Terry Wildman, main author of the new translation, with pastor Jeremiah Rood, who reviewed First Nations Version in the July/August issue of Foreword Reviews.

Enjoy the interview!

The text opens with some helpful insights into the First Nations and the people involved in making the translation. Can you give us an insight into how the work was done? I have the sense that this was very much a community effort. How did that work?

OneBook Bible Translators from Canada and Wycliffe Associates from Florida suggested I form a translation council to begin the process. A council of twelve was decided upon, all of whom are Native American/First Nations from differing tribal nations and geographical locations. With guidance from OneBook and Wycliffe Associates, we spent nearly a month in Florida and Calgary, Canada, working with the Translation Council determining how we would translate over 180 key terms from the Greek. We also decided upon the method of translation.

Since I had been working for several years developing the writing style, it was decided that I would prepare the initial draft of each book. As the project manager, I would then invite several reviewers (all Native) to give feedback using Google docs. When the review was complete the text would be entered into ParaText, a software developed for Bible translators. Checks were made in reference to the key terms and other translation requirements.

While I already knew the members of the Translation Council, our friendships grew much deeper over the initial physical meetings and have continued to grow in the time since. Also, new virtual relationships have developed over the years as new reviewers were added to the project. This branched out into ministry connections with other organizations such as Cru Nations, Native InterVarsity, Montana Indian Ministries, Foursquare Native Ministries, and many more. A detailed explanation of the translation process can be found on our website: https://firstnationsversion.com/fnv-translation-process/

I’ve never had the chance to translate the Bible. My own seminary training was more about how to provide pastoral care and lead a congregation, than how to translate Greek and Hebrew. So, I’m impressed. I do wonder if you might speak a bit about what it was like to tackle a project of this scale? Did anything surprise you about the work?

In my wildest dreams I never imagined that I would ever translate any of the Bible. I have served as pastor to several churches for about twenty years of my life, and have both formal and informal training. It was after living among the Hopi people in Northern Arizona that the seeds of the idea of an English New Testament were planted in my heart. But it was about ten years later that I finally committed myself to what I felt was a sacred task. I never considered myself qualified and the idea seemed overwhelming and daunting, but no one else had done this kind of translation work and I could find no one who was doing it. Once I committed myself, the support and help came from OneBook and Wycliffe Associates who came alongside me, undergirded all my efforts, and helped with funding and ideas like forming a translation council and using a group method.

What surprised me about this work was how easily, in some cases, the Scriptures could be phrased in a way that relates to our Native languages. Some of the metaphors were already expressed in the New Testament Greek. Phrases like “walk as Jesus walked.” and “walk in love,” are obvious examples. In some cases, we simply expanded on what was already there in the Greek text.

There are many translations of the Bible; I’m guilty of having a shelf full at home. In reading yours, I was really struck by the importance of names in your translation. You call Jesus, for example, Creator Sets Free, who is described as a “wisdom keeper” and a “seed planter.” I’m hoping you could tell us how you choose the names you did?

I self-published two books that were precursors to the FNV New Testament. The first was Birth of the Chosen One (the Christmas story), and a harmony of the Gospels called When the Great Spirit Walked Among Us. In those early translations, after talking with many Native friends, I decided to translate the meaning of the biblical names to connect with our Native naming traditions, where names have meaning. In the FNV New Testament, our council approved that practice. Each name, both of people and places, was researched in Greek and sometimes Hebrew and then given a Native slant to the meaning. A simple one is Abraham as “Father of Many Nations” (Romans 4:16-18). Wisdomkeeper is simply a cultural equivalent to rabbi or teacher or even Lord in some places. Translating the meaning of the names has been the most significant positive feedback we have received for the FNV. We have a glossary in the back pages of the FNV NT that explains many of these terms and why we translate them the way we did.

Your text begins with a fabulous prologue that sets the New Testament firmly in the context of the Hebrew Bible. I really loved this part of your work because it transformed all those discrete biblical books into a new narrative that really emphasizes the First Nation aspect of the text. Honestly, I’d hoped that style would have continued throughout, but instead, you went for the traditional chapter and verse most readers will know. Can you speak to how you chose to format your text and what you were hoping to achieve?

We wanted the FNV to be used not only as a contemplative reading experience but also for Bible study in groups. Numbered verses make that possible. We are also hoping to have the FNV New Testament available online with sites like Bible Gateway. So to do that we needed the numbered individual verses. I would like to see a publication done without the verses that can be read as a story. The harmony I published, When the Great Spirit Walked Among Us, is of course presented without any verse numbers and provides that kind of reading experience. And I have had really good feedback from others because of that. I would love an eBook version that could remove the verse numbers and section headings as an option. But that might be down the road.

The Bible has some difficult texts inside it. I’d like to focus on just one: Galatians 4:21-31, which Phyllis Tribble famously named a “Text of Terror” for its depiction of women and slavery. I really appreciated how you softened that text by noting that the “son born to the slave woman was born of broken desires, by trying to force Creator’s promise to come true.” The text is a tough one to understand, given the difficult themes. Can you speak to how you handled texts like these and other more difficult aspects of the Bible?

The biblical world of the Hebrew Scriptures and the 2nd Temple period in the time of Jesus was a very different world than today. I have learned it is the job of translators to be true to the words of the text but also to the cultural practices and worldviews of the period. One thing about the Bible is the original authors did not hide the ugly behaviors and practices of the characters involved. Not everything Abraham or others did was a reflection of our Creator’s heart. He was working with broken people who walked in broken ways. Jesus, in my view, came to reveal to us the true heart of God, correcting and redirecting his followers to what the Creator’s good road, the kingdom of God, would look like when untainted by the world. So when it seemed appropriate, and in line with Jesus’ teachings, we softened some wording, but sometimes it can’t be softened. We left much for the pastors and theologians to clarify as most translations do. In some places we added clarifying statements in italics, such as in Paul’s discussion of head coverings in 1st Corinthians 11:3-16.

I love it when the Bible offers up some new theological ideas and I found your text to be just full of insight. The language of the translation is often beautiful, when, for example, you describe the blessings of the good road as the kingdom of God. I love it because it shows how active and possible the hope of Jesus is. It’s like a path or road vs a place. I find that to be a powerful difference. I’m wondering if you could speak some about how you developed those theological phrases? For instance, I have the sense you very intentionally considered whether or not to include gendered language?

Yes, minimizing gendered language was intentional where it did not change the meaning of the text. We are of the understanding that the Great Spirit is neither male nor female. However, the original writers of the New Testament present the Great Spirit as Father, a male term. We see these terms as cultural metaphors when used to speak of the Great Spirit. However, it is clear in the Scriptures that Jesus was literally born into this world as a male human. In this translation, we followed in the footsteps of the writers of the New Testament and used male pronouns for the Great Spirit. This was also the practice of many of our Native people as they speak of the Supreme Being.

Many “theological” phrases emerged as we delved deeper into the translation process. The more we translated, the more ideas rose to the surface. We tried to speak in a more traditional Native way, but also translate for a contemporary audience. It truly was a balancing act.

Many of the “theological phrases” were already attested to in other places in the Greek text. Walking is understood as how we live our lives. So walking the good road with Creator Sets Free equals living in the ways of the kingdom of God or being a disciple of Jesus. We intentionally stayed away from what could be called “colonial language.”

Our goal has been to make this language serve our Native peoples, sort of redeeming it from its many negative effects. I spent a lot of time reading early writings by Chief Joseph, Black Elk, and many other early English speakers from our past. Their way of speaking English worked its way into the translation. Black Elk spoke of “sending his voice to the Great Spirit” as a way to visualize prayer, so we adopted that in many places. At times we also borrowed ideas from Native Christian Theologians, like George Tinker, whose writings helped us with conveying the idea of “the kingdom of God” as Creator’s good road.

I know you are working on turning this text into a film. Can you tell me a little bit about that process and what we might have to look forward to on that front?

For more than a year now we have been working with the artists and staff of the Jesus Film Project in Orlando, Florida, a branch of Cru. With the leadership of a former Disney artist, Dominic Carola, and a Jesus Film Producer, Irv Klaschus, we are creating what many are calling a groundbreaking animated short film. The film is based on the FNV of Jesus feeding the 5,000 and walking on the water with Peter from Matthew’s Gospel. I am the narrator and writer of the adapted story. This film should be finished by the end of June 2021 and released online sometime shortly after that. It will be a great introduction to the First Nations Version and we anticipate its use in Bible studies and at events where the Gospel can be introduced to Natives in a culturally relevant visual storytelling format.

Have I missed anything you’d love to talk about?

InterVarsity Press has contracted with Christian Audio for an Audio Book of the FNV New Testament. We are hoping to have several Native narrators involved. I will be one of them. This will be such a good thing because our Native People have traditionally been oral storytellers.

Jeremiah Rood