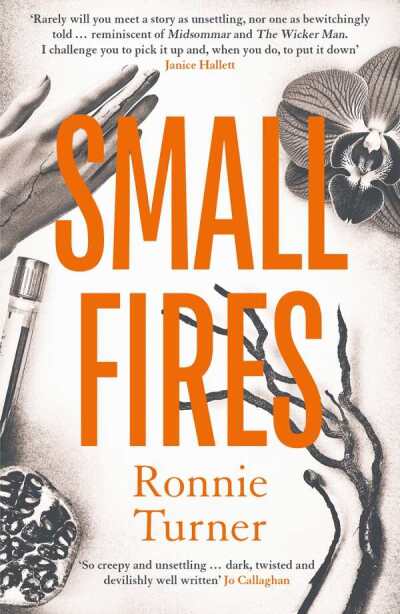

Reviewer Isabella Zhou Interviews Ronnie Turner, Author of Small Fires

Gothic novelist Ronnie Turner has some pretty strong feelings about female beauty. In fact, the way beauty marks young women as targets for sexual abuse infuriates her. In the interview below, she cites the Pleiades myth—Orion stalks seven sisters so relentlessly the girls end up needing Zeus’s help to escape into the night sky as stars—as an example. “There the sisters are safe,” she says, but “shouldn’t the sisters have been safe anyway? Why did they have to be removed? Why did their beauty condemn them? It made me furious enough to explore this topic in the book. The many faces of beauty. How it can be advantageous, dangerous. How it can be coveted and even weaponised.”

That book is Small Fires, a “nightmarish yet beautiful” novel which earned all manner of adulation from Isabella Zhou in her starred review for Foreword. Needless to say, getting Ronnie and Isabella connected for a conversation made too much sense to pass up.

We’d be remiss if we also didn’t mention four more thrillers on our recommended shortlist from the 2024 INDIES Book of the Year awards: The Vixen Amber Holloway (gold); The Death of Clara Willenheim (silver); Releasing the Reins (bronze); and Bone Pendant Girls (honorable mention). Foreword Reviews digital subscriptions are free.

So many of the events and character relationships in Small Fires are shaped by the blighted land that is God-Forgotten. What was your process for creating such an evocative and unforgettable setting subsumed in an almost tangible collective fear?

The God-Forgotten was a way to challenge myself. I almost think of it as an exercise in “world-building.” It is set just off the coast of Scotland but I wanted it to feel as if the world had choked this island out of its mouth. And for the island to feel as if it might have come from those dark, grotesque fairy tales we find as children. To achieve this, I conjured an entire culture for the community residing there, a history to fill their books, and a religion for their restless minds. The Folk, as I call them, believe a devil fell to their land thousands of years ago and to this day he governs them, culling their numbers once every year. They are a community living in perpetual fear. To enrich the lore of the God-Forgotten, I researched folklore from around Britain and Europe, Greek myths, even stories from the Bible. I also utilised true historical events such as the Dance Plague and the Laughter Epidemic to enrich the island. It was a real labour of love. But the creation of the God-Forgotten and its community gave me the most joy I have ever had writing a novel.

As we follow Lily around God-Forgotten, we, along with her, collect a panoply of horrifying local folklores and histories. In the “Then” sections of the novel, we are also exposed to the dark fairy tales Della used to terrorize Lily. How did you come up with these vignettes, myths, and legends? What role do these types of stories within a story play in shaping understanding of our personal and collective histories?

For the retrospective “Then” scenes, I wanted the reader to have a glimpse of Lily and Della’s childhood, their dynamic, to better understand how they became such a strange and toxic pair. I also wanted to explore the frightening influence a storyteller has over the listener. Using classic fairy tale tropes as my parameters, I created six vignettes which Della uses as a device to torment her younger sister. Stories have power. Aesop’s fables and so many fairy tales are cautionary tales, designed to teach children about morals. Stories can do damage too, they can blister and harm innocent minds. They can be passed down like generational trauma.

I have beautiful memories of my mother reading me fairy tales as a child but I also have memories of discovering that Cinderella wasn’t the sanitised version Disney depicted. In actual fact the step sisters cut off their heels to fit into the glass slipper. So, stories, be them good or bad, have an inspiring and at times frightening power. So I weaponised the vignettes to show how stories can harm, as well as heal. And above all, persevere through time.

Almost all of the characters in your intensely character-driven thriller have secrets and are not what they initially seem—they all wear masks, so to speak. Who is your favourite and why?

I enjoyed writing my two sisters enormously. They are the stars of the show. But as a collective, The Folk are my favourite character. I used them as a device to build atmosphere, to lay down red herrings, to pay tribute to classic fairy tales. They are the backdrop. A prop. But they are also such an intrinsic part of the story. I find them fascinating. And I poured so much imagination into their creation. I wanted them to feel like a cult almost (yes, I did a lot of research into cults) to feel feral and a little frightening but complex, twisted by their own folklore. I also wanted the reader to sympathise, to observe the humanity in them. To show that humans are more than the sum of their parts.

Most of the named major characters are women, girls, or otherwise associated with femininity. I was struck by their complexity: they could be both victims subjected to and perpetrators weaponising the beauty and innocence the other male characters project onto them. How is this relevant to contemporary culture and media?

I think as women, we often feel we must repress the darker, “messier” parts of our psyche and adhere to a preconceived image of perfection. To look pretty, to behave correctly, to exist as society dictates. Many of us have come across the term “pretty privilege,” which to be honest, I find frightening—that women (and men) might have advantages simply because of their appearance when other qualities are disregarded.

The power of beauty stretches back through history: the Egyptians wore kohl to embellish their eyes, Aphrodite, the most beautiful of the gods, was revered for her appearance. Humanity is fascinated with it. But juxtaposed with this are the dangers of beauty. If beauty is coveted, why? Is it unrealistic? Even dangerous?

In Small Fires, I speak of the Pleiades. Seven sisters of Greek myth who are pursued by the vicious Orion for their beauty. The sisters decline his advances. And so the seven sisters are hunted for their beauty. In the myth, Zeus takes pity on the sisters and gives them to the night sky. The women become a constellation, guiding lost folk to safe places. There the sisters are safe. But what I ask in Small Fires is this: shouldn’t the sisters have been safe anyway? Why did they have to be removed? Why did their beauty condemn them? It made me furious enough to explore this topic in the book. The many faces of beauty. How it can be advantageous, dangerous. How it can be coveted and even weaponised. I also wanted to say very boldly that women need not adhere to typical beauty standards. We can be feminine and feral. We can be messy and unpolished and strong as gods.

Like many other responses to Small Fires, I characterized your storytelling as “gothic.” Was it your intention from the start to write a piece of gothic fiction? In what ways does your book incorporate and/or play with gothic themes and conventions?

I’ve met many readers in my day job as a bookseller who have been uncertain what Gothic Fiction actually is. Gothic Fiction is Shirley Jackson, it’s Daphne Du Maurier, it’s Emily Bronte. In Gothic Fiction, you are given isolated, claustrophobic settings, atmosphere that builds to a crescendo. And you are offered a lens on human nature and social criticism. Gothic Fiction explores big themes and big questions, often with a beautiful prose. This genre asks the reader to really consider what they have read, to think deeply and be curious.

I love writing this genre because it gives me a sense of freedom. It’s unrestrictive. I can play and explore and experiment with characters and plot. I think what I find the most challenging about writing this genre is building that atmosphere. It’s extremely challenging. A fine art and if you lose your way and get it wrong, it’s very hard to recover.

Your “about the author” at the end of the book says you are a “Waterstones lead bookseller.” Did this experience shape, in any way, the writing of Small Fires? Does it have any influence on how you create stories, in general?

Yes. I always say being an author and a bookseller go hand in hand. It’s the perfect marriage because it allows me to meet readers organically, to learn from them what works, what doesn’t work about the books they read. It’s like market research, if you like. You can learn so much just listening in a bookshop. And so it does affect my writing. With Small Fires, the original concept was so much darker. The island community were going to be the villains. It had a very The Handmaid’s Tale-esqe energy to it. But I realised that the story would be too dark, off-putting. It needed a redemptive arc, it needed to be a story of survival and recovery as well. I needed to give the reader a chance to breathe, to have a strand of goodness in there. So overall, I continue to learn lots from readers in the bookshop.

Can you give us a sneak peak at any current projects you are working on?

I’m working on my next novel now. It is gothic fiction. I can’t say much about it but to give you a visual: think The Binding meets Rouge meets Brothers Grimm.

Thank you for such thoughtful questions. You’ve really “seen” what I’ve tried to achieve with this book.

Isabella Zhou