Reviewer Isaac Randel Interviews Todd Goddard, Author of Devouring Time: Jim Harrison, A Writer’s Life

What if I own more paperclips than I’ll ever use in this lifetime. My other possessions are shabby: the house half painted, the car with no muffler, one dog’s got bad eyes and the other dog’s a horny moron, even the baby has a rash on her neck, but then, we don’t own humans. My good books were stolen at parties long ago, two of the barn windows are broken, the furnace is unreliable and field mice daily feed on the wiring. But the new foal appears healthy though unmanageable, crawling under the fence and chased by my wife, who is stricken by the flu. Not to speak of my own body, which has long suffered the ravages of drink and various nervous disorders which make me laugh and weep and caress my shotguns. …

God, we love that last line of this excerpt of a Jim Harrison poem from Letters to Yesenin. It speaks so perfectly of Harrison’s humor, frailty, spot-on wordcraft, and the primary reason he kept those shotguns: for hunting ruffed grouse and woodcock in the thickets and uplands of northern Michigan—to pluck and roast whole over woodfire and serve with ample pours of Cote du Rhone.

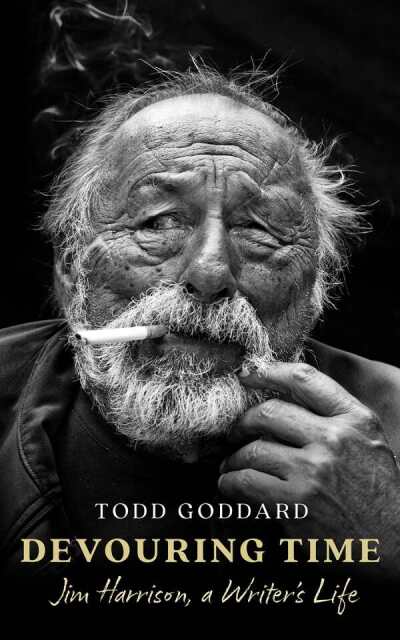

Over his fifty year writing career, Harrison is best known for novellas and novels including Legends of the Fall, A Good Day to Die, Sundog, The Road Home, The Woman Lit by Butterflies, Brown Dog, and The Beast God Forgot to Invent, but his twenty or so collections of poetry may have the most lasting power of all his work. He died at his desk writing in 2016, and many of us at Foreword still think of him often.

Todd Goddard’s biography of Harrison, Devouring Time, earned a glowing review from Isaac Randel in Foreword’s November/December issue and connecting the two for a conversation about the grizzled master was obligatory.

With Harrison’s ode to paperclips on our mind, let us point you to four INDIES Book of the Year Award-winning collections in the Poetry category.

In many ways, Devouring Time is more than just a portrait of a single writer. It’s also a portrait of the wider publishing world, and especially of its long-standing division between so-called “reputable” writing (from coastal publishing houses and insular MFA programs) and so-called “commercial” writing (Hollywood scripts and “genre” novels). Your portrayal of Harrison has him publicly rejecting the literary establishment of his day, while also privately feeling snubbed by that same establishment for its failure to recognize his artistic achievements. How—if at all—do you think Harrison’s attitude toward the literary world would have changed if he had received more serious recognition from the literati more frequently in his career?

My guess is that he would never have fully relinquished some animosity toward the literary establishment. I think to some extent Harrison fed on his feelings of rejection, and it helped to fuel his literary ambition and efforts. It was useful for him to think of himself as an outsider, as “off to the side”—the title of his 2002 memoir. Even if the literary establishment had thrown open the doors and showered him with awards, he would have found reasons to distance himself from that establishment. But he might also have felt more personal fulfillment, and more literary accolades might have provided him with the kind of official validation that he had always wanted. I think he would have been proud of the markers of serious recognition of his artistic achievements.

Throughout your biography, you explore Harrison’s penchant for “self-mythologizing” and exaggerating his own outlandish feats. At the same time, your biography shows that Harrison really was a figure who pushed himself to the extreme limits of endurance, whether in creative output, or feasting, or drinking. Much like with Hemingway’s fans, many of Harrison’s most devoted readers continue to see him in an almost super-human light. Which aspect of Harrison’s character and life do you think continues to be the most misunderstood?

Not unlike Hemingway, parts of Jim Harrison’s life remained intensely private. For instance, while he readily shared stories about his life in his journalism and essays—ones that often projected his larger-than-life persona and helped to cultivate a devoted readership—he rarely talked about this family and his marriage in any meaningful or personal way (There’s also a notable lack of correspondence between Harrison and his wife, Linda, in his collected papers). What’s often overlooked or misunderstood are the tremendous struggles he underwent throughout his life. On a public stage, Jim often seemed inexhaustible, capable of great feats of eating and drinking and writing—and he was—but those activities exacted a serious private toll on his mental and physical health. Harrison would suffer from an increasing long list of ailments and his suffering, often cloaked behind his wonderful sense of humor and genuine affability, is much less understood. Those struggles, his deep depressions and illnesses, as well as his doubts and fears, are deeply woven into his fiction and poetry.

One of the most humorous sections of the biography describes a disastrous conference at Stony Brook University during the university’s heyday as a site for an attempted nationwide poetry renaissance. In addition to showcasing the incident’s debauchery, it also offers a window into a kind of university culture which may not exist anymore—a time when American colleges made ambitious attempts to recruit the best and brightest poets of their generation into a single institution, in order to spur a wider literary renewal. How has the impact of colleges and universities on the literary world changed since Harrison’s time teaching at Stony Brook?

Many American colleges and universities still recruit the best and brightest writers, especially for MFA programs. But since Harrison’s time at Stony Brook in the late 1960s, the number of such programs has increased dramatically. There are literally hundreds of MFA programs across the country and enrollments are generally increasing. So the impact on the wider literary world is significant. Poetry and poets mostly reside today in MFA programs, and whether that’s a good or bad thing is a hotly debated topic. Harrison was no fan of such programs, which he likened to Ford Motor Plants, and he thought they stifle creativity and are insular and overly safe, beliefs harbored since he was a teenager. Harrison held romantic views of poetry and poets, and universities and college degrees didn’t fit into his vision. Poets, he thought, should get out into the world, travel, work at various jobs, meet different people, and have a range of experiences. How else would you have anything to write about?

Across his career, Harrison wrote about an impressive range of topics: food, hunting, sporting, and, seemingly, any subject for which there was a handsome commission. As you explore in the biography, Harrison’s work toward these side projects ended up creating devoted readerships who may otherwise have never read his poetry or fiction. What do you think was the main draw for Harrison to seek out these seemingly obscure publishing opportunities? Did he choose these kinds of apparently “non-literary” projects because he knew it would put him in touch with new demographics of readers, or was that only a happy accident of some other underlying reason?

Money was the main factor in Harrison’s decision to pursue journalism and write on a broad range of topics, especially early in his career, I would argue. As he readily admitted, he simply couldn’t make ends meet by writing poetry alone, and money for his fiction was slow to come: It wasn’t until the publication of Legends of the Fall that he started making real money from it, and most of the money came from Hollywood and screenplays. As one of Harrison’s magazine editors once told me, Jim was always hungry for more work.

Still, Harrison was savvy about the publishing world, enough to recognize the audience he was building through his journalism. And I think he enjoyed it, the writing about food, hunting, and sporting. When he got started in journalism, magazines still paid well for stories, and they would cover his expenses. They paid for him to go fishing in Ecuador, provided him with new cars to drive across the country, and covered his travel to the USSR to write about horseracing.

Harrison’s contacts across the worlds of publishing, journalism, and Hollywood put him in contact with some of the most consequential creative figures of his day: fellow novelists and poets, but also screenwriters, executives, agents, and actors. Your biography covers the many friendships and collaborations which emerged from these encounters, not all of which remained amicable. Which of these celebrity partnerships did you find the most rewarding to research, and what can they tell us about Harrison’s importance to the larger culture of his time?

My first thought is Jack Nicholson. Harrison and Nicholson had a very close friendship for many years. There’s a great story in Devouring Time about how Jim first met Nicholson on a film set in Montana and how the actor later helped to support him during the writing of Legends of the Fall, his best-known work. That was the book that helped to earn Harrison a new level of fame, and its success brought him to Hollywood where he befriended a host of other actors and directors, like Harrison Ford and Sydney Pollack.

Perhaps Harrison’s richest and most productive relationships, however, stemmed from his time at MSU, where he first met Tom McGuane, his lifelong friend, and which later connected him to his literary agent, Bob Datilla, and friends like poet Dan Gerber and Richard Ford. These relationships eventually extended to a large group of writers and artists in and around Livingston, Montana, that included Russel Chatham, Richard Brautigan, William “Gatz” Hjortsberg, Jimmy Buffett, and others. He would spent time with this group in Montana and Key West, fishing and drinking, and the group would come to be loosely dubbed the “Montana gang.” They arguably inspired each other in many ways, and their friendships and activities and inherent competitiveness collectively energized them and bolstered their creative output.

The question of “legacy” is everywhere in this biography. It shows up not only in your own critical analysis of Harrison’s works, but also in the many confessions and statements which Harrison made about his own career. Which elements of Harrison’s legacy today do you think he accurately predicted, and which elements do you think he would have found surprising?

It’s probably too early to tell just how Jim Harrison’s literacy legacy will ultimately shake out, but he would be absolutely thrilled to know about the work that Joseph Bednarik—Harrison’s long time poetry editor—and Copper Canyon Press have done to promote his poetry. The 2021 publication of his Complete Poems and the reissue of many of his books, all with powerful introductions written by Colum McCann, Joy Williams, Terry Tempest Williams, and others, would probably delight him to no end. Harrison thought that if he was remembered at all, it would likely be for his poetry, and that prediction appears to be holding up, though I certainly wouldn’t discount his novels, novellas, and nonfiction.

There’s an idea out there that writers, not scholars, ultimately determine someone’s literary legacy, and I would add readers to that list. Harrison was never embraced by the academy, largely because he himself shunned it, but many writers are vocally indebted to him, and his readers are an extremely loyal group. If my experiences writing this biography are any indication, Harrison’s readership hasn’t gone anywhere, and his readers are just as eager to read and re-read his work and share their passion for him with others. That bodes well for his legacy.

Isaac Randel