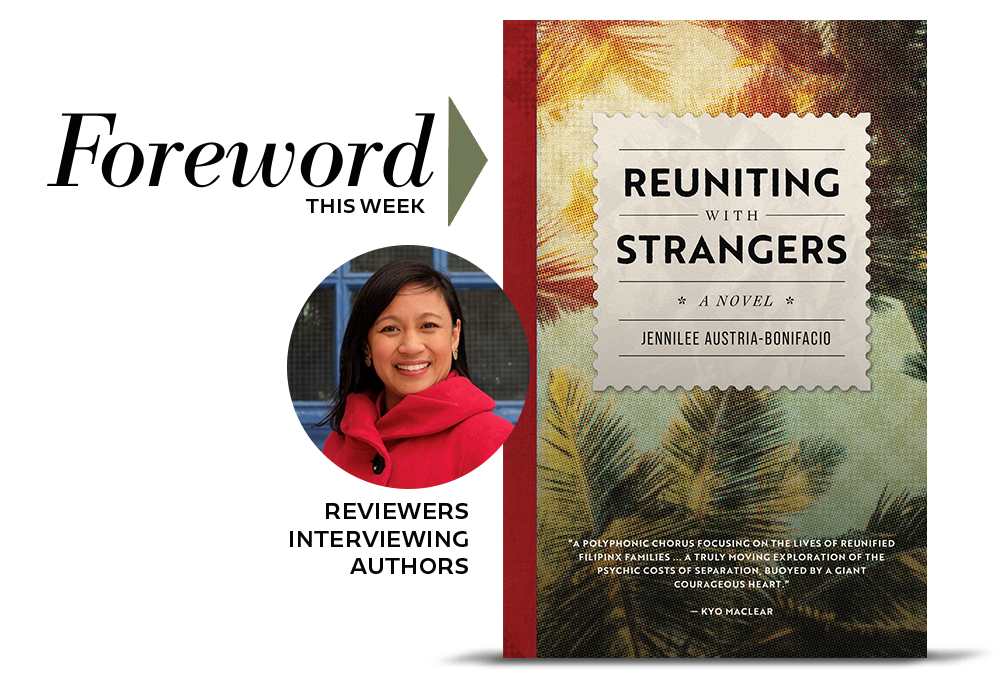

Reviewer Interviews Jennilee Austria-Bonifacio, Filipino Author of Reuniting with Strangers: A Novel

Toronto’s Filipino community has a friend in today’s guest, Jennilee Austria-Bonifacio. Through her educational initiative Filipino Talks, she has built bridges between immigrant Filipino families and thousands of school teachers and administrators across Canada. Jennilee personally offers professional development for teachers with Filipino kids in their classrooms, conducts surveys of Filipino students, and even introduces Filipino literature and poetry to interested Canadian educators. A topic for another day is how she found time to write Reuniting with Strangers, which earned a starred review from Eileen Gonzalez in the May/June issue of Foreword.

Before we get to Jennilee and Eileen’s conversation, grant us a quick minute to talk about the tens of thousands of immigrants, Filipinos included, who travel to the US under temporary work visas that legally bind them to their employers and make them especially vulnerable to labor trafficking and slavery. H-1B and H-2B are two of several work visa programs that are associated with abuse. The problems arise when the immigrant workers seek to leave their jobs for better pay elsewhere only to have their employers threaten to report them to immigration officials to keep them from going. It’s not a small problem: 1.3 million work-related temporary visas were issued by the State Department in 2023. While exact numbers of victims are difficult to ascertain, more than two thousand individuals were referred to US attorneys for human trafficking offenses in 2021.

Jennilee and Eileen, let’s talk about the Filipino diaspora in North America and why they provided such rich fodder for a novel.

The novel has such a unique format: interlocking short stories, many of which utilize different storytelling methods (some are prose, others are epistolary, etc.) and different narrators who each have their own understanding of and opinions on events. What is it about this combination of formats that makes it the best way to tell this story?

As I was crafting this manuscript, I thought about the best way to reach the audience who had inspired my stories in the first place: Filipino families coping with reunification.

I decided to get my messages to readers through a variety of ways: a series of résumés, a kundiman songbook, a flurry of text messages and e-mails, a self-help guide, an instruction manual, and more—I love the idea of surprising my readers as they find stories told in unexpected forms. I wanted readers to see that literature doesn’t have to be academic, with big words and long, winding sentences; it can be accessible and told in everyday ways.

Monolith, a young neurodivergent boy who has trouble adjusting to life in Canada, binds the novel together, even though he plays a central role in only a few of the stories. Was he always intended to be the focal point? Why is Monolith, out of all the characters in the book, the right choice to “glue” everything together?

Monolith’s story was the first one that I wrote. When I finished it, I knew that I didn’t want the entire book to be about him, but at the same time, I didn’t want to let him go. Inspired by a real newcomer boy—one whom I’d never met but had heard about after working in his former school—I knew that Monolith was special.

As a school board consultant through my initiative, Filipino Talks, I work with Filipino newcomers. And my youth often say that they feel voiceless: nobody asked them if they wanted their parents to leave them behind in the Philippines; nobody asked them how they felt to be raised by extended family; nobody asked them if they even wanted a future abroad. The youth often tell me how voiceless they felt as children, and how voiceless they still feel as newcomers.

It was important to me that the youth see that Monolith—a non-verbal child—shows up at moments of change. We witness Monela trying to speak to him over a video call; Ginette watching him throw a tantrum at Roots; Rey seeing him on a fundraising campaign video; Lolo Bayani feeling a sense of purpose when this little boy enters his life—and Monolith, although he technically has no voice, uses his actions and emotions to inspire change in everyone else.

Although the formats change with every chapter, with new characters who are also going through the challenges of family reunification, through Monolith’s spirit—his anger, his outbursts, his need to reach out—there is a cohesive story being told throughout the book that unites everyone.

Many of the stories revolve around a parent/child relationship. Why did this particular kind of relationship interest you as the basis for a book?

Through Filipino Talks, I’ve surveyed over 1200 Filipino students. And in school after school, the biggest challenge that the newcomer youth are facing is family reunification.

While most of my students were separated from their mothers for eight years, I’ve also worked with students who were apart from their mothers for up to twenty years. And I have students whose parents were a big part of their lives, like Jermayne’s Mumshie, who called every Sunday and kept Jermayne and their father in the loop about what to expect abroad. And I also see parents like Vera, Monolith’s mother, who is a complete stranger to her son and consequently sees him lash out in some very big ways.

Through my work, I’ve seen so many parents and youth wanting to reach out to reconnect but not having the words to start building this bridge. That’s why the book is so centred around the miscommunication between parents and children: because of everything that goes unsaid after so many years apart.

Some of the most devastating moments come when a character expresses themself through writing, like in “Seven Steps to Reuniting with Your Teenage Daughter,” in which Ginette processes her frustrations and disappointments with her mother and Canada by creating a how-to guide. The fact that characters like Ginette cannot really speak to anyone else and must vent through pen and paper is heart-rending. What do you think they hope to get out of these writings?

Since frontline work can be quite emotionally heavy, on nights when I’d lie awake, worrying about families as they struggled after so many years apart, I’d write about what was on my mind.

Not only was this a form of self-care, but it also helped me to unpack the many facets of family reunification: not only women learning to live with their spouses and children again, but the bigger picture—the parents left back home who needed care, the guardians engaging in a custody battle over the children they raised, the Canadian-born generation who feel a deep animosity towards their newly-arrived relatives, the non-binary children who hope to find a new chosen family, and so much more.

I’m proud that almost half of the stories in Reuniting with Strangers come from young voices: Monolith, Ginette, Monela, and Jermayne. That’s why the book’s dedication is “For the 1200+ Filipino Talks students whose stories kept me awake at night”—this book is truly for them.

Reuniting with Strangers is about the experiences of women who leave the Philippines to settle in Canada, but it deals with many broader, more universal themes that can apply to all immigrants, like homesickness, loneliness, and alienation. What do you hope immigrant readers take from your book?

It was so important to me to show many sides of the newcomer experience.

For instance, Rolly came to Canada as an international student and embraced caregiving when he became a young father, but we can contrast him with Gina, who felt like she had no choice but to go abroad to support young Ginette and her own mother after her husband and father died. While some newcomers choose a life abroad wholeheartedly, some make this decision out of desperation, and others fall somewhere in between. It is my hope that newcomers can identify with at least one person in this book.

And what do you hope people who are not immigrants get out of it?

For non-immigrant readers, my main goal is the same one that I have when I facilitate Filipino Talks professional development sessions for educators and frontline workers: to build empathy.

I want to show them everything that could be happening behind closed doors: custody battles over text messages and e-mails, the rich heritage and language that many newcomers leave behind in the Philippines, the impact on a storied family when there is no one to inherit a legacy, and so much more. I want them to see my community and our non-binary youth; our experiences with anti-Black racism; our reaction to often being seen, first and foremost, as workers; and more.

Lastly, it was important to me to bring readers into Filipino homes in different parts of the world: from a cliffside town on the Tagaytay Ridge to the closed OFW apartments of Riyadh to our communities in the desert of Osoyoos, the Arctic world of Iqaluit, the suburbs of southern Ontario, Sarnia’s Chemical Valley, Montréal’s Côte-des-Neiges, and Toronto’s Little Manila.

As someone who was born and raised in the diaspora, I hope that Reuniting with Strangers finds a warm place in hearts across the globe.

Eileen Gonzalez