Reviewer discusses MLK Jr. with Joseph Rosenbloom, Author of Redemption: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Last 31 Hours

For this final, hours-belated Black History Month post for February, we’re headed back fifty years to the final hours of Martin Luther King Jr.‘s legendary life. At the time, in the early months of 1968, King Jr. was focussed on his Poor People’s Campaign, an antipoverty initiative that wasn’t all that popular with his staff and supporters. In addition, his opposition to the Vietnam War had ostracized him from former allies, and, of course, he was also at odds with the FBI and others in the US government for various reasons. It wasn’t an easy time for King Jr., to say the least.

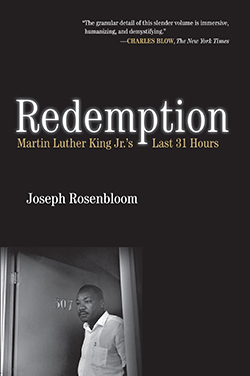

Today’s Foreword Face Off features Joseph Rosenbloom, author of Redemption: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Last 31 Hours, a fascinating look at “King’s final days,” as well as “all the historical momentum that was lost on April 4, 1968,” in the words of Jeff Fleischer in his review for Foreword. Jeff recently caught up with Joseph via email and the following conversation sheds all manner of new light on the great civil-rights leader.

What was the origin of the idea to write a book focused specifically on Dr. King’s trip to Memphis and the last 31 hours of his life?

As a summer intern in 1968 at the Memphis morning newspaper, The Commercial Appeal, I heard stories about what happened in Memphis in March and April. I filed away the idea that I would like to look into that episode of his life. Years later, I read the most important books about the Memphis chapter of Dr. King’s life. I hit on the idea of exploring the Memphis events surrounding him, along with what he was doing in the last stage of his life, by structuring those stories in the form of a close-up narrative about his last thirty-one hours. That struck me as a unique, powerfully evocative way to get at those important stories.

You conducted interviews with several of the key figures in the story. How did that shape the rest of your research process?

Interviews with two leaders of the garbage workers’ strike led me to devote a chapter to the circumstances surrounding the strike, including a detailed profile of one of them. I looked at FBI records and other accounts of the strike, notably Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign by labor historian Michael K. Honey, for an understanding of the labor union history of Memphis and the grievances and actions of the city’s garbage workers.

An interview with Andrew Young, executive director of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, underscored for me the depth of Dr. King’s conviction that he was going to die a violent death and how he had come to terms with that fate. I then looked into theological works to research the concept of Christian redemption.

What new information did you find most surprising as you conducted your research?

By digging into the hearing transcripts of the US House Select Committee on Assassinations and Memphis police files, I learned that the police provided only a four-man security detail for him. Second, I learned that even that security force was on duty to protect him for less than eight hours, all on only one day, April 3. The degree of police indifference toward Dr. King’s security surprised and shocked me.

I also discovered how much Dr. King was counting on success in recruiting the Invaders, a local Black Power group, to join a Memphis march he was planning for April 8 as a critical part of his strategy for keeping the protest nonviolent. Despite much effort on his part, as I detail in the book, he was not able to win the Invaders over. They refused to commit themselves unequivocally to nonviolence.

The book provides a lot of context about the struggles the Poor People’s Campaign was going through when Dr. King chose to stop in Memphis. How do you see that campaign’s role in Dr. King’s legacy?

The Poor People’s Campaign is integral to Dr. King’s legacy. He was vowing to bring thousands of poor people to Washington. He would lead them for weeks, perhaps months, of protest. He would engage in massive civil disobedience, demonstrating in the streets of the nation’s capital and flooding congressional and executive offices with protesters. They would plague Washington until lawmakers enacted the sweeping, multibillion-dollar antipoverty program he was demanding.

He knew that the tactics he envisioned for the Poor People’s Campaign might result in his long imprisonment. He knew that the controversy swirling around the campaign was putting his life in greater danger. That he was running such risks reflected the urgency that he felt about eradicating poverty, once and for all. That he was redirecting his movement and dedicating himself to that cause indicated how strongly he held that American citizens had a fundamental right to live free of poverty. How could the depth of his commitment to ending poverty not be part of his legacy?

You also capture King in some private moments, with friends and trusted associates. How did you about crafting these scenes?

I crafted the scenes, first, by collecting as much vivid detail as possible from my interviews and research. In each interview, I asked my subjects to recount their experiences as stories. I looked for ways to personify their stories and build suspense. The object was finding a compelling narrative thread to string the material together.

Redemption really shows all the “what if” moments that led up to the assassination, both the oversights and the coincidences. Which of these factors seem most obvious to you in retrospect?

To ask “what if” along the way from the start of the Memphis strike to Dr. King’s assassination is to speculate about how things might have turned out if only this or that had happened or not happened.

One might ask, for instance, if Dr. King would still be alive had he not agreed to speak at a rally for the garbage workers in the first place. Or, what would have happened had he not decided on the spur of the moment to return to Memphis so that he could lead a pro-strike march?

Or what if Mayor Loeb had been more willing to negotiate a settlement of the garbage workers’ strike? Could the police have protected Dr. King had they been more intent on providing security for him? Had Dr. King not hesitated on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel to banter with his aides in the parking lot below on the evening of April 4, could James Earl Ray have shot him? The “what ifs” could go on and on.

Generally, what do you hope readers take away from the book?

I hope that the book imparts to readers the full meaning and resonant emotion of King’s last hours in Memphis. He was then embarking on a new and ambitious crusade to end poverty in America. That subject is a central theme of Redemption.

Further, I hope the book spotlights the subject of poverty in a way that inspires readers to look at it through King’s eyes and come to understand him in a more complete and nuanced light. The book shows him as he pivots ideologically and tactically in a direction that was displeasing many of his most ardent supporters and intensifying the hostility toward him among his enemies. The book shows a man under crushing pressure from many sides. But it also shows his responding energetically and courageously in his quest for social justice and personal redemption.

Jeff Fleischer