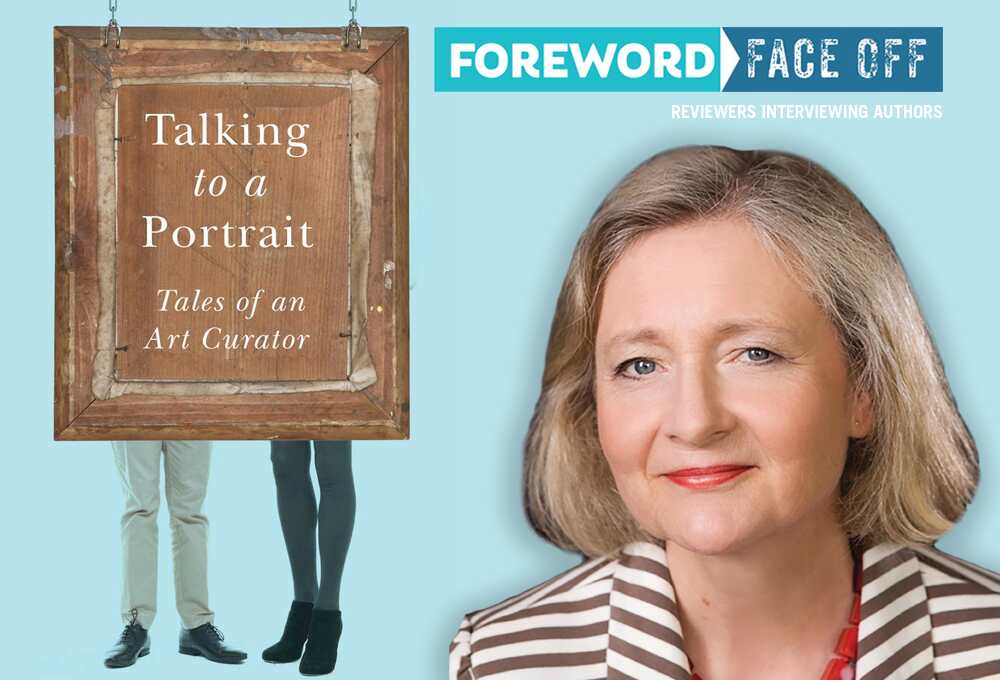

Reviewer Claire Foster Interviews Rosalind Pepall, Author of Talking to a Portrait

To walk a nature preserve, view constellations in the night sky, or snorkel over a coral reef is to experience the beauty and complexity of this earth. For the curious child, such occasions are a source of innocent wonderment—as well as countless questions. Mommy, mommy what’s the moon made of? How do fish breathe underwater?

To be young is to wonder why, and where, and how.

Not surprisingly, many studies have shown that the average adult doesn’t understand a great deal about the natural world either—because there’s simply too much to know. Hey, Siri, why do we only ever see one side of the moon and never the other? Why don’t trees freeze solid when the temperature drops below zero for weeks on end?

But don’t fret if nature’s intricate processes often leave you confused. We encourage you to take a childlike approach and ask silly questions without embarrassment—a mindset that can also be applied to other parts of your life.

Fine art, for example. Do you have a solid grasp of what makes a piece of art valuable or important? We venture to say, no, you don’t, unless you have a fine arts degree or grew up in a family of collectors. And that’s to be expected. Art appreciation is an extremely broad, specialized skill—a fact we learn from Rosalind Pepall, former Curator of Canadian Art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal, and author of the recently released Talking to a Portrait: Tales of an Art Curator.

In her review of Talking for the September/October issue of Foreword, Claire Foster writes that Rosalind animates and humanizes the art she features, helping readers to “enter each piece and, once there, how to get comfortable with seeing the world in a new way.”

With the help of Véhicule Press, we set up the following FaceOff interview between Claire and Rosalind, one we’re sure you’ll enjoy.

Claire, take it from here.

Your memoir focuses on fifteen distinct objects—from Tiffany glass to Edwin Holgate’s “Ludivine”—from a wealth of paintings and other works. How did you choose these specific pieces to write about?

Most of the chapters in the book focus on one art work, which offers a unique story—either about the artist, the history of a piece, or its style. After all, the book is about questions that an art curator has to answer: who made it and when; where was it created; what is the significance of the subject; who owned it; and above all what is so special about the work?

Sometimes, a chapter will deal with a painting or a decorative art object or even a whole exhibition, as I was privileged to work under two masters in the preparation of big thematic shows of art in every medium and with exhibits borrowed from around the world. They were Pierre Théberge, director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts for eleven years, and his friend, Jean Clair, the celebrated art historian and author from Paris, who is now a member of the illustrious Académie Française. Through the stories, I reveal the different aspects of a curator’s job, from interpreting art to simply playing detective and turning up surprising results.

Talking to a Portrait discusses Canadian history and artwork; the two are inextricably linked. The fifteen objects in your memoir are quite diverse. Why was this important to you?

In my career, I trained and worked in both Canadian art and architecture, as well as in international decorative arts and design. I started my career at the MMFA as a curatorial assistant, then served as an exhibition coordinator, guest curator, Curator of Canadian Art, and finally Senior Curator of Decorative Arts. After over thirty years in the museum world, I was able to draw stories from a wide range of experiences. In one case, I tell about borrowing the National Hockey League’s Stanley Cup for a show on modern silver design, and in another, I experienced a moral dilemma in trying to convince an elderly lady to lend a portrait she had lived with all her life.

The variety of art works examined in the chapters appeals to a wide audience. In fact, of the fifteen chapters, half deal with Canadian art and the other half deal with international art works (including American).

The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts has limited its exhibitions due to the COVID-19 pandemic; many galleries are completely closed. How are you getting your art fix during this time, and how can people explore some of the iconic pieces you describe from the museum’s collection?

The COVID-19 lockdown, which has kept us all home for months, has actually led to museums posting inventive ideas to show off their collections. On the internet, it was possible to see and hear museum directors and curators discuss their favourite art works, or art conservators talking about the process of restoring paintings. In a way, my book fits into this theme of looking behind-the-scenes at the role of a museum curator.

For those who wish to have more information on the art mentioned in the stories, I have included in the book “endnotes,” which give the published and archival sources for my research.

During the pandemic, I have especially enjoyed watching the weekly YouTube series presented by the Frick Collection, entitled “Cocktails with a Curator,” during which Chief Curator Xavier F. Salomon and Curator Aimee Ng discuss the significance and provenance of a particular painting or sculpture from the collection of this New York museum. Also I have enjoyed the online conversations between the Art Gallery of Ontario’s director, Stephan Jost, and individual museum directors around the world, who worried about how they were going to open up their galleries and present exhibitions in the post-COVID period.

From the first chapter of Talking to a Portrait, you describe your experience as a woman in the male-dominated arts and culture space. What has changed for women curators since 1978, and women who work in museums?

I don’t believe that I brought up the idea that the arts and culture community was male dominated. In fact, when I first started working at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in 1978 as a curatorial assistant, the female curators and guest curators outnumbered the male curators; the head of the Education Department was female, as was the head of Public Relations—both expanding departments. However, the first female director of the museum, Nathalie Bondil, was only appointed in 2007. But, the National Gallery of Canada from 1966–1981 and from 1987–1997 had outstanding female directors, and the present director, as of 2019, is Alexandra Sasha Suda.

During the 1980s, many female art historians held important curatorial positions in Canadian museums as well, and right now at the MMFA, the small group of curators (roughly eight) is majority female. As the museum community has grown, there has been more room for female directors.

In the United States, I have collaborated with a number of female curators, but it would seem that the traditional large museums are still run by male directors, but I have not seen the research on the gender makeup of museum administrators to speak beyond my own personal experience.

Claire Foster