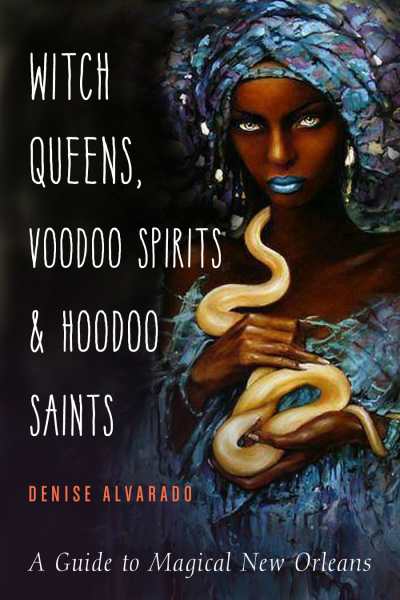

Reviewer Catherine Thureson Interviews Denise Alvarado, Author of Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints: A Guide to Magical New Orleans

Take a look again at the book title featured in this week’s interview and check your reaction. That’s right, check it hockey style—especially if you don’t think Voodoo, Hoodoo, and Wicca should be taken seriously in spiritual terms. You’re being unfair, to say the least.

In the following conversation with Catherine Thureson, Denise Alvarado brings to light any number of reasons these practices, traditions, and folkways deserve respect. As a Voudou practitioner and Hoodoo rootworker, she walks the walk.

In her review for Foreword, Catherine called Denise’s latest book “fascinating as it examines New Orleans’ rich spiritual landscape,” and our interest was not to be denied.

There is such a diverse cast of characters in this book. How did you identify who to include?

This is such a great question. And as you can imagine, one I asked myself numerous times as I was deciding who to include in Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints. I wanted to accomplish a couple of things by writing this book. First, I wanted to highlight some of the more commonly known figures, provide perhaps a different perspective, and tell a part of their stories that had not been told before. I wanted to contribute to an already established body of folklore by introducing some lesser-known figures that have been forgotten over time. And then there are those I wanted to bring out of the shadows and into the light so that people could get to see them, perhaps for the first time. In essence, I wanted to broaden the public story a bit, digging into ancestry and culture and spirit in a way that redirects stereotypical thinking towards a narrative that is meaningful, authentic, and representative of New Orleans’s magicospiritual culture.

Each story in the book features a figure not often heard of outside the local tourist economy. Some stories have resided among old, unpublished manuscripts of the Federal Writers Project and in the dusty newspaper archives of the 1800s and 1900s. Yet, they are as relevant today as they were in their own time. Annie Christmas, for example, seeks racial and gender equality. She is gender fluid and is an enforcer of justice. She uses magic and prays to her African gods to navigate life challenges. She has a great sense of humor and loves life, but she ultimately commits suicide. What makes such a strong woman suicidal? We can see from her story that her strength can be alienating—people fear her even as they respect her. But ultimately, it is the loss of her true love that brings her down. She tried for years to find a soulmate, then she lost him. She would rather join him in death than live without him. Her story is entertaining, but it is also very tragic and human.

Betsy Toledano was another woman who lived in New Orleans in the 1800s and was a Voudou queen. During that time, Voudou was against the law there, and the local police were constantly harassing black folks. They would routinely break up gatherings of people practicing their Afro-Creole religion, and once a queen was identified, she would be an ongoing target. Betsy Toledano was one of the Voudou queens who fell in that category.

Unfortunately, we don’t know much about Betsy as a woman or voudouist in pre-Civil War Louisiana. We know about her activism from newspaper reports. But these reports give us quite a bit of information about her beliefs and character. What makes Betsy stand out is that she was an activist and spoke plainly and directly to the judges presiding over her cases. Her story is important in part because it illustrates how little things have changed concerning the relationship between the judicial system, people of color, and Indigenous religions. But wow, what courage and conviction she displayed by telling a white judge in antebellum Louisiana that she was proud of her Congo religion, had no intentions of hiding it, and had a right to practice it.

I can relate to Betsy in many ways. I know what it is like to be interrupted by the police while in the middle of a ceremony. When people see or hear things that look different, they like to call the cops even though we aren’t bothering anyone. When I moved to a small town in the Midwest in the nineties, for example, I met with the local fire department to inspect a firepit we built for ceremonial purposes. I had gotten permission from the town to build it and wanted to avoid any problems in the future. We got permission, and the fire department approved of the fire pit and even said, “you look like you know what you are doing.” So, I proceeded to hold a ceremony.

The ceremonial preparations lasted all day, and a medium-sized fire burned for quite some time until we entered the lodge. Well, we weren’t in the lodge but for about fifteen minutes before a neighbor called the police on us. So, I had to exit the lodge and deal with the cops. Luckily, I had a letter from the city with permission to show them, so I was prepared. Can you imagine being a pastor of a church and having to have a permission slip from your city to hold your service?

Betsy would not have been so lucky because it was against the law to practice Voudou in the 1800s, and no permission slips were to be had. Every time she wanted to serve her community, she would face nosy, intolerant neighbors and be taken to jail if caught in the act. We might think, well, that was a long time ago, and things have improved. That is indeed the case; however, it is notable that I was eighteen years old when the American Indian Freedom of Religion Act was passed in 1978. It has only been since 1994 that President Bill Clinton decriminalized the use of peyote as a religious sacrament. The Native American Church is still subject to regulations imposed by their colonizers. So, it has not been all that long ago for me and everyone else who practices a traditional Indigenous religion.

Interestingly, in Louisiana, an archaic law remains that outlaws the practice of Voudou within the city limits. As far as I am aware, it is not enforced; however, the law remains and could be revived at any time, in essence, criminalizing the thousands of people who practice Voudou there.

With so much of the lore of New Orleans spiritual history being passed on through oral storytelling, and what often seems to be conflicting accounts of the people involved, how did you go about researching the individuals in this book?

It was important to me to present an accurate account of the characters in the book and to link historically documented facts with oral tradition and esoteric knowledge in the construction of each chapter. I used several sources, including academic databases, the Federal Writers Project, newspaper archives, and my personal library. That said, sometimes the best account of a given culture is oral tradition.

In an academic setting, stories are corroborated by written sources. I also try to corroborate written sources with oral history. I talk to fellow practitioners about things I read, get their opinions, and listen to their experiences. These kinds of conversations are always helpful, and I always come away with a clearer understanding of a particular issue or individual spirit.

Are there any individuals that you would like to have included that did not make the cut and can you tell me a little bit about them?

There are so many that were not included—where do I begin? The Loup Garou and Bras Coupe are two I would have liked to include, but both of those would have been long chapters, and I had a word limit. The Loup Garou is Louisiana’s version of a werewolf, and who doesn’t love a good werewolf story? But did you know there is an actual cult of the Loup Garou? It is a topic I want to tackle at some point, but I want to do it justice and spend the amount of time necessary to tell the story respectfully. I also would have liked to include a chapter on St. Jude because, as the patron saint of lost causes, he gives people hope, and if ever humanity needed hope, it is now.

Do you have a favorite historical figure from the book and can you share why or why not?

I love them all, and naming a favorite figure feels like asking who my favorite child is! However, if I had to choose among my favorites, it would be Lala Hopkins, the Hoodoo queen in the 1930s and 1940s. I also have the highest regard for Marie Laveau.

Lala was just a fantastic, eccentric conjure woman and Hoodoo priestess. She was dirt poor, but boy was she proud. She was proud of her abilities and proud of her spiritual lineage. She always paid homage to the Mother of New Orleans Voudou, Marie Laveau, when discussing her work. She gave credit where credit was due. She was a two-headed conjure doctor, meaning she worked with both hands, left and right-handed magic, and she walked in the world of spirit and mundane. As a Hoodoo priestess, she performed initiations. She was good at what she did—maybe too good. Unfortunately, she was hired by people in her community to fix or curse other people in the community, which made her a target of those on the receiving end. She frequently moved to avoid conflict.

Because of her lower social class, Lala was assumed to be a drug addict by the Federal Writers Project interviewers. They judged her by her looks—poor, black, and disheveled—and offered to buy her some dope “because she looked like a dope addict” in exchange for an initiation. While she could have gotten angry and reacted in any number of righteous ways to their offer, instead, she simply refused it. I love her response to them. She essentially stated, “I don’t use it, but I know who does. The spirits are my dope.” Boom.

Marie Laveau is considered the earliest Hoodoo and Voudou conjurepreneur. She was a consummate businesswoman in a day and age where that was rare due to social circumstances. She owned the city and had an information network that would rival anyone today. She was quite influential. For example, Marie worked out a sweet deal with Father Antoine that allowed her to use the church grounds for her Voudou ceremonies on Sunday afternoons so long as she brought more people to church with her. She held up her end of the bargain, which increased the size of her own as well as Father Antoine’s congregation.

Every Hoodoo and Voudou website, Etsy shop, eBay seller, Amazon seller, TikToker, and Instagrammer who promotes their for-profit spiritual business owes a debt to Marie Laveau. She was really the first to make a business out of Hoodoo successfully. Her style of Voudou combined the mystic rites and saints of Catholicism, making it more palatable to her ever-growing congregation of white folks. It also served to keep the Church happy. Because she combined her spiritual practice with making a living, we all owe her.

Aside from celebrating her business savvy, I also admire and respect Marie Laveau for her humanitarian efforts. She nursed the sick and buried the dead. She visited criminals on death row and built altars in their cells to pray. She housed Indigenous market women in her home and gave shelter to runaway slaves. There is so much to love about this woman; I could and did write a book about her, The Magic of Marie Laveau.

If there was just one lesson that you want people to take away from reading your book what would it be?

Outsiders often laugh at Voudou and quickly label it illegitimate, comical, and trivial. Or they perceive it as something truly sacrilege and the work of the devil. I want people to understand that Voudou is a legitimate spiritual tradition and Hoodoo is a legitimate spiritual folkway. Both served to empower the enslaved and people of color to withstand harsh social conditions. The functions of empowerment and problem solver remain today; just as any religion has its prayers and sacred rites, so do the African and Indigenous-based spiritual traditions of the South. The stories of the central figures in my book hopefully help to convey these truths.

How should someone who wants to learn more about Voodou pursue that study, both academically, and perhaps spiritually as well?

I strongly encourage anyone with a sincere desire to learn about Voudou, Hoodoo, rootwork, conjure, and witchcraft to take time to learn the history of the traditions—the tragic and the beautiful. Learn how things came to be what they are. Learn how things were in Africa and how the traditions adapted to the New World under traumatic conditions. Learn about the relationships between Africans and Native Americans. Understand how incredibly resilient our ancestors were. Learn who they are. My book, Witch Queens, Voodoo Spirits, and Hoodoo Saints, helps in that regard. I introduce readers to each witch, saint, and spirit so they become real. At least, I hope they do. When they become real, a connection can be made with the past and present. It’s no longer a joke or subreddit. We keep our ancestors alive with our reverence, and they help us and guide us.

It is also important to vet your potential teachers. Seek out actual practitioners who are willing to teach and don’t expect anything for free. While you can find folks willing to teach for free on social media, be grateful when you find them. People have forgotten about respect for elders and tend to be incredibly rude and arrogant. Just because you have family from wherever, are broke, or are serious about learning does not entitle you to the mysteries. They say Voudou chooses you, not the other way around.

Read as much as you can. My books are thoroughly sourced, and readers can learn more by checking out the references and bibliographies at the back of any of my books. I’ve provided hundreds of them. That said, you must read critically. And by “critically,” I mean, question everything you read. Does the author back up their conclusions with some sort of proof? Most popular books do not provide any support for their views or indicate where they learned about the subject. It’s not that there is nothing of value in popular books—of course, there can be. But it makes it much more difficult for a neophyte to discern fact from fiction or standard practice versus an eclectic and personal approach. Once you have a good foundation, it is easier to determine what is what.

Nowadays, everyone is a critic and quick to criticize a book because they don’t like the author, the author is of the wrong race, or simply writes about things in a different way than the reader thinks. Critical thinking is conflated with criticism. I once had a young person from an Eastern European country tell me what I wrote was wrong because it was different from what they had learned from a white Jewish woman from California—a person who is not from my culture or a practitioner of Voudou. Make that make sense.

I personally did not start a formal study of Voudou until I was an adult, well into my thirties. One of my degrees is in cultural anthropology, specializing in Native American studies. From there, I went on a natural exploration into the traditions of my birthplace and culture, and I expanded into intentional learning about the African-derived traditions. It fascinated me. I recommend that anyone academically inclined take some African studies and Native American courses. There is a lot more available now than when I was in college, so take advantage of it. Find professors who are also practitioners who have written books, buy them, and read them. Find the practitioners who have written books, buy them, and read them, too.

Of course, a most important aspect of learning about Voudou is interacting with practitioners. If you can make it to New Orleans to participate in any number of the public rituals there, do so. You can meet others of like mind who are more knowledgeable and can help you find a house to join if you want a spiritual family. I caution against initiation, however, until you have studied for several years and have gotten to know the people in your house well and have a thorough grasp of the tradition. Be sure you are a good fit.

Finally, talk to your grandparents about the old ways. Ask them questions about old wives’ tales and cures and what not. Listen to their stories. A lot of folkways are embedded in our elders who sit right in front of us in the living room. The elderly usually love to tell their own stories. Don’t discount them for any reason. Give them space to speak and see what you can learn about the folk practices of your own family. You just might be surprised with what you learn.

Denise Alvarado website: creolemoon.com

Catherine Reed Thureson