Reviewer Brooke Shannon Interviews Catharina Coenen, Author of Unexploded Ordnance

Writers are fearless—we’ve heard it said so often it has become a cliche. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t a courageous few who really are drawn to grapple with issues that are so vexing the rest of us shield our eyes and skulk away.

Today’s guest offers a case in point: Catharina Coenen’s grandfather was complicit in atrocities committed by the Nazis, while her grandmother somehow survived devastating firebombings and near starvation in Germany during the war. Catharina learned this from anecdotes her grandmother shared during her childhood, but only after her grandmother’s death was she able to resurrect these memories “to a place where they could be fully seen.”

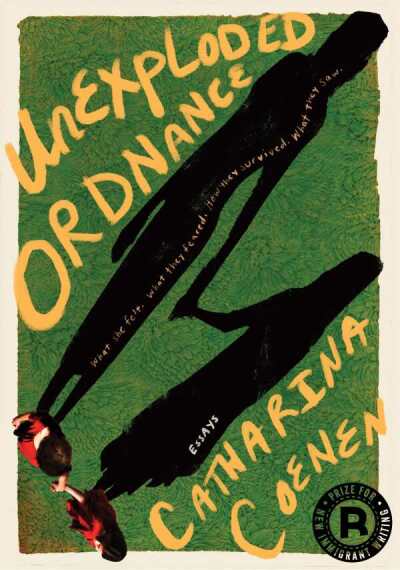

Unexploded Ordnance is Catharina’s memoir and, according to Brooke Shannon, it “pivots around a compelling moral inquiry: can the suffering endured by Germans during World War II be

acknowledged without eclipsing or excusing the immense suffering that Germany inflicted?” Brooke says that Catharina “approaches this tension with honesty and care, situating her family’s experiences of bombings, dislocation, and hunger within the larger context of collective guilt and responsibility.” She closes her starred review by calling the book “a lyrical excavation of silence, memory, and the hidden traumas that echo across generations.”

Enjoy the conversation.

Unexploded Ordnance isn’t a traditional memoir; it reads like a constellation of essays linked by image, memory, and research. How did the metaphor of excavation or ordnance shape how you built the book’s structure?

Unexploded Ordnance grew from wartime anecdotes that my grandmother shared throughout my childhood. After her death, I began committing these fragments from a subterranean entity that haunted my memory to a place where they could be fully seen. During the process, I did extensive research on the circumstances under which German women and children lived during World War II. Rather than trying to construct a single, consecutive narrative, I allowed each story to create its own self-contained opportunities for learning.

While collecting facts about the bombings of Germany, I stumbled across documentary films about ongoing bomb-removal projects. I felt a kinship with the men who unearthed, defused, and removed these bombs. We were all scratching and scrabbling in the dark, trying to prevent the past from blowing up the present. We were trying to understand the mechanisms that create danger in order to render them harmless. We were choosing, over and over again, to do this work because we knew in our bones that it had to be done.

When I first assembled the essays into a book, I separated them with short scenes describing this bomb-removal work. When early readers reported that these scenes took them too far away from the main characters—my mother, my grandmother, and my aunt—I removed them. My publisher then encouraged me to reinsert intervening pieces, but to focus them more on my obsessions with language and translation—my own tools to banish the long shadows of wartime trauma across generations.

Early in the book, you write about “schweigen,” meaning silence as something one does. Since finishing the book, how has your understanding of silence evolved?

The publication date of Unexploded Ordnance falls within a period of American history in which, yet again, silence is a political act that will determine the future. As an immigrant whose ability to stay and work in this country was, for decades, contingent on keeping my Green Card, speaking and publishing outside my immediate academic field always felt fraught with the potential loss of the life and livelihood I had built for myself.

I am now a citizen. But I hear recent statements by government officials threatening dissenters with “denaturalization” as yet another attempt to enforce silence. On the other hand, I am witnessing how public threats and legal actions against opposition leaders are helping more and more Americans understand the silences of German citizens in the 1930s and 1940s—how those silences were created, and how silence, enforced by fear, enables ever greater repression of dissenting voices.

Naming the silence, or “silenting,” of onlookers as an act, rather than as a neutral failure to act, is pushing me to move against these acts of silencing, against the fears that want to silence me.

You describe English as “the shovel” with which you could dig for your mother’s childhood. How did writing in English, rather than German, change your relationship to these stories and to your own sense of identity?

For me, having an English-speaking audience—first close friends and instructors, then students in writing classes, and later readers and editors—was key to putting my mother’s and grandmother’s stories on the page. In German, everyone already knew some version of these stories, because they lived in family memory. In English, I found listeners who wanted me to explain, to take them into experiences they had never known. That meant I was no longer just the keeper of my grandmother’s stories, but their translator.

Writing in English also made me visible as “German” to my friends and readers in a way that felt deep and connecting rather than shallow and alienating. For decades, I had grown used to my German accent, when detected, prompting remarks that made me feel my home country was seen mainly as a tourist attraction (“I’ve always wanted to live in a castle” or “I’ve always wanted to drive on the Autobahn”). But now, the people who asked questions about my stories truly wanted to learn about me and my family’s experiences. Their questions felt genuine, connecting my own emotional experiences to those of my readers rather than alienating or “othering.”

By writing in English for the people who surrounded me in an English-speaking country, I became less alien, more fully seen, and more at home in my chosen community.

In exploring your grandfather’s life as a German soldier, you confront questions of inherited guilt and complicity. What responsibilities do descendants carry when telling such histories?

I hesitate to make generic statements about “descendants,” because the experiences that shape us—and the circumstances under which we tell the stories of those we came from—differ widely. Even when I want to say that the responsibility of anyone telling histories of any kind is to tell the truth, to the best of their knowledge, I wonder if there may be circumstances in which the “contract” between storyteller and audience includes a shared understanding that truths may always be slanted, partial, or metaphorical.

So, speaking strictly for myself, I felt a responsibility to find out what I could about how my grandparents might have contributed to the horrors of Nazi Germany. I also felt responsible for acknowledging that any truths I commit to paper are imperfect, incomplete, and colored by my own experiences. I believed that what I owed my grandparents (and perhaps my readers) was to approach the past with genuine curiosity.

To write about German suffering during the war without acknowledging the much greater suffering that Germans caused feels deeply irresponsible. Talking about German suffering at all feels both necessary and problematic in ways that stalled my writing again and again. At the same time, not giving voice to the suffering of ancestors who caused suffering is to deny these ancestors their humanity. And I am convinced that lasting peace requires that we see each other as fully human.

You write, “The scientist in me pores over census data … but early childhood is coded not in words and dates but in sound and taste and touch.” How did you balance the precision of research with the sensory and emotional truths that resist documentation?

For me, research, sensory experience, and emotion are deeply intertwined in the writing process. Research was essential to help me feel into the experiences of the people who appear in the fictional, or speculative, segments of my essays. Any fiction writer will probably agree: we need to share a great deal of knowledge to draw readers into a world and a character’s experience.

As I wrote, much of that research initially made its way onto the page. I felt I had to support every narrative move by citing sources to prove I wasn’t simply making things up. Toward the end of my first year of writing, a workshop participant suggested that I trust my abilities as a storyteller more than my abilities as a researcher—that I needed to shift that balance. The remark gave me permission to expand the speculative passages of my essays and significantly pare back the quotes and citations.

I realized that what I most needed from writing these essays came when I let myself slip under someone else’s skin—when I lived the stories from another person’s perspective. I could then limit the expository passages to the often-shocking details that were invisible to the narrators of the anecdotes, and to scenes showing how those stories continue to reverberate in my family today. Often, this meant cutting a fifty-page essay down to ten or twelve pages. Submitting work to literary journals also helped me make these cuts. I often asked my writing groups to identify the “must-have” passages in a lengthy essay.

The book’s final passage suggests that our stories, like a “line drawn on a sphere,” return to where they began and connect across time and place. What do you hope readers take from that sense of connection between personal and global histories?

When I read this question, a line from “Know When to Move,” a song written by John McCutcheon, popped into my mind. I first heard McCutcheon’s lyrics at a Rebel Voices concert in the early nineties, and the song has never left me. “Know When to Move” is about solidarity between factory workers in Soweto and those in a US factory town, urging listeners to recognize their own stories in what is happening around the world.

To me, McCutcheon’s message is not only about recognizing patterns across space but also across time. If we don’t understand how patterns of oppression repeat, if we don’t see ourselves in others, we lose the ability to organize as a people to resist repression. But if we can see the suffering of women and children during World War II as something that might befall us or those we care about, we may move from simply reading about them to letting their stories fuel us, to break our own silences, and to stand up for the people and values we want to protect.

Brooke Shannon