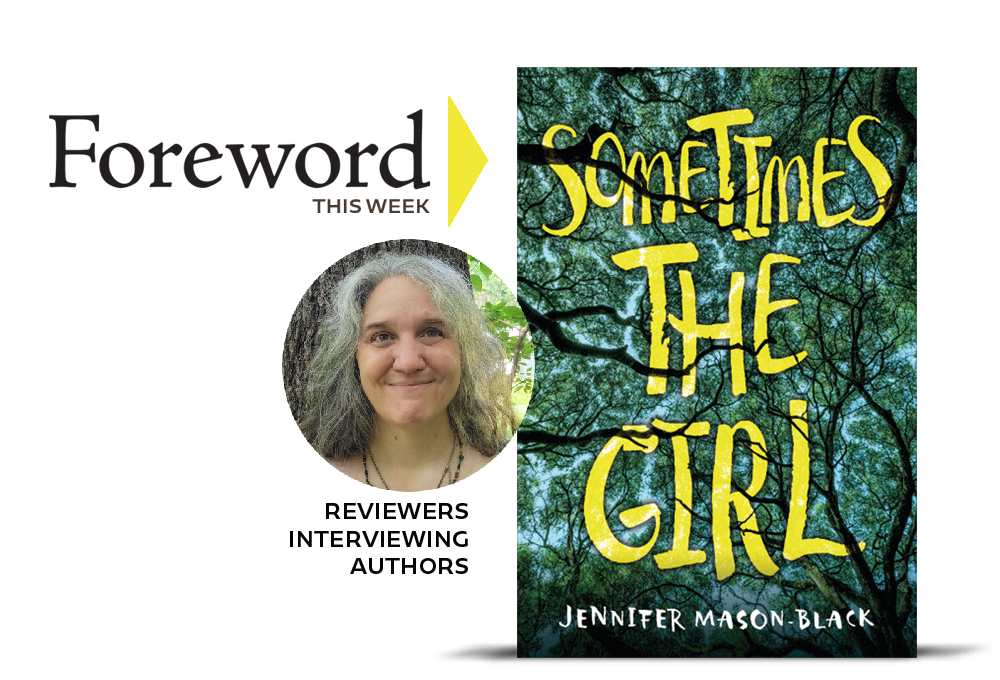

Reviewer Aimee Jodoin Interviews Jennifer Mason-Black, Author of Sometimes the Girl

Watching the reviews come tumbling in before every issue of Foreword is both stressful and suspenseful: stressful because there’s lots of editing and layout work to do; suspenseful because we never know which books are going to electrify our reviewers, earn a starred review, and trigger one of these Foreword This Week interviews—always reserved for very special books and authors.

Which tees up today’s conversation with Jennifer Mason-Black.

Longtime reviewer Aimee Jodoin uses the words lyrical, touching, elegant, poignant, impeccable in her starred review of Sometimes the Girl, Jennifer’s queer YA mystery that leans literary as it explores questions of fame, writing, and integrity. Complex and nuanced, it is a book that we can’t recommend highly enough.

Check out the four other YA projects that appeared in the May/June issue of Foreword Reviews. In case you were wondering: digital subscriptions to the magazine are free.

Both Holi and Elsie, among the other characters, have held life-upending secrets from their loved ones. In what way does telling or continuing to keep a secret inform Holi and Elsie’s perceptions of themselves?

I think for both of them, honestly, for so many people, the secret becomes secondary to the shame wrapping the secret. For Holi, that shame has a tangible container: her own body. Her understanding of herself is at odds with how she believes people—the actions of one person so easily feel like the beliefs of all—see her corporeal self. That she’s able to share that deep wound with Mouse speaks to her resilience, and to the part of her that held tightly to the truth of herself.

Elsie though … Elsie breaks my heart. She’s held her secret so long and so closely that it’s completely reshaped who she is, who she might have been. A glass pane exists between her and the world, her own hated reflection overlaying all she sees. It’s stripped her of connection with everything dear to her, her creativity most of all. Her battle between supporting Holi and driving her away from a creative life is one fought between the young artist she once was and the master of betrayal she now believes herself to be.

How do you envision Elsie’s life being different if she had continued writing?

In order to have continued, Elsie would have had needed a reckoning with Tongues. I think that’s true in general for an author who bursts out of the gate with a big book, that question of how to move forward creatively when the reading world craves something recognizable from you.

But for Elsie, of course, the question of creativity is so tightly bound with questions of truth and betrayal. I don’t think she could have returned to writing without finding some compassion for herself, some fury for those who treated her as a pen and not an artist. And if she had been able to gain those things? I believe she would have written deeply and passionately, would have created work that stared humanity straight in the eye. Her writing would have contained both the wildfire and the wildflowers that returned to burnt woodlands, rage and love every step of the way.

Would she still have ended up in a quiet neighborhood in Amherst, Massachusetts, would she still have been a mother, would she have been a different kind of one, would she have remained a Red Sox fan? All our lives are full of these sorts of forks in the road. The one thing I believe is that at least some of Elsie’s shame could have transformed into grief, and then, hopefully, into healing.

Near the end of the book, a note Elsie wrote to Holi reads: “Writing is a vocation I recommend no woman choose, as it may well cost her things it never asks of men and in ways she cannot imagine. However, once writing has chosen her, no woman should be forced to enter its arena sans sword and shield.” What “sword and shield” would you recommend women, writers or otherwise, wield in a world that demands so much of them?

So many things, of course! However, given that we are living in a rapidly decaying capitalist system, I have to go with community. I say that as someone with very little community. I have debilitating anxiety that affects all aspects of my life, including human connection, so I understand just how high a hurdle it can be to forge strong connections.

All the same, we as a species are not meant to live our lives in isolation. One of the great lies we’ve been taught is that money is our salvation. The reality is that we’re the ones to save each other. In the places and times that things have fallen apart, success has come from humans reaching their hands to help. For women artists, having others who cheerlead and challenge them; who celebrate their growth and mourn losses with them; who can help keep the lights on and bring food to share when the pressure to simply survive leaves little space to create … those connections can easily be the difference between a book and a deleted file. Community doesn’t need to be vast or specific to artists though, just full of love and belief and respect and evolution.

Based on the conclusion of the book, I imagine your opinion is that a writer’s estate should not publish books posthumously without the deceased writer’s prior consent. That is my opinion, as well—that we should respect a writer’s wishes, no matter how desired their unpublished works may be. What are your feelings on instances where books have been published after a writer’s death in the past (Harper Lee, etc.)? How do you feel about the loss of stories we will never read?

I’ve never felt that an individual owes the world their creativity. The act of sharing a story, the act of receiving one—is, at its heart, a generous and trusting experience. That piece of it has been commercialized almost to oblivion, so of course many readerships understand storytelling as a product, rather than as a choice made to communicate.

In posthumous publication, simple situations do exist. For example, a writer with every intention of publishing work who dies too early to complete that goal. I’d have no issue with my family publishing a novel I was never able to find a home for.

That’s not what you’re asking though—I’m just being skittish. I have compassion for everyone who struggles with the desire to further a deceased writer’s legacy, who feels it is an act of love. My belief, though, is that an artist’s work is a conversation with the world. In any passionate conversation there are hypotheses that we quickly recognize as flawed, beliefs that change as we listen deeply to others, fleeting thoughts we realize belong solely to our internal life. As much as I might love to hear all those unsaid things, as much as I might miss their revelations, I see intellectual autonomy as fundamental to the creative process. It is hard to destroy one’s own work; requesting other do it posthumously may truly be a final request for help, not a door left open for the world to enter.

What books have you read that have affected you in the way Elsie’s book affected Holi?

I’ve always loved The Little Prince. From the very first time I read it and all the many many times since. I was homeschooled as a kid, at a time when it simply wasn’t a mainstream thing, and I always felt a bit like a traveler in a strange world any time I was taken from amidst the wild things and set in more mass-produced surroundings. I also struggled with grief as a teen, so I eventually turned to it as a guidebook on how to live through loss. I can still recite parts of it.

What’s next for you? What are you writing now?

In terms of YA, I have nothing cooking currently. Sometimes the Girl is actually the last in a group of three sister books; Devil and the Bluebird is the first. The middle book has a direct character-and-timeline overlap with Sometimes the Girl, while navigating a very different sort of mystery. I’d love to see it in print.

As for what I’m actively writing, it’s an adult speculative fiction about a girl whose ability to heal led to her being used to steal magic from other children. In a post-climate-collapse landscape, the now-adult woman crisscrosses the country on a quest for atonement while fleeing the billionaire who bankrolled her complicity for his own mysterious gains. It’s about the power of rivers and community and the human ability to change for the better. And it has a dog named Jack who’s a very good boy.

Aimee Jodoin