Rediscovering America's Oldest Indigenous Spiritual Text: The Popol Vuh

Reviewer Camille-Yvette Welsch Interviews Jemshed Khan, Author of Popol Vuh: The Maya Hero Twins in Xibalba

Over the course of five hundred years, Western Europeans colonized many indigenous lands in the Americas, often entailing slaughter and ruin. The Spanish conquest of the great Mayan civilization certainly makes the short list of existential tragedies because the Maya were so accomplished in writing, mathematics, astronomy, architecture, and agriculture for more than 3500 years—with a population that may have reached sixteen million people in 900 AD.

Moreover, the Spaniards systematically confiscated, burned, and destroyed as much Maya literature as possible in their efforts to Christianize and colonize the Maya peoples and replace their written language. As a result, there’s a great deal we don’t know about their culture. But one important religious document, the Popol Vuh, somehow survived and it is now considered to be one of the world’s foundational religious texts.

Today’s guest, Jemshed Khan, joins us today to talk about the “creation-myth” stories that make up the Popol Vuh and his decision to reinterpret it “as an adventure that brims with life, drama, spirituality, and character.”

Jemshed’s Popol Vuh: The Maya Hero Twins in Xibalba recently earned a glowing Foreword Clarion review from Camille-Yvette Welsch and they both were keen on the idea of connecting for a conversation.

In what ways do you think other creation stories have crept into the Popol Vuh as a result of the translation process if at all?

That is a great question. Let me begin by mentioning that the Popol Vuh is a stunning Maya narrative from the mid 1500s that originates from the K’ichi’ peoples of Mesoamerica. It is a remarkable living text and considered one of the world’s foundational sacred religious texts. As such, it reflects the universal themes identified by Joseph Campbell in terms of archetypes, the Hero’s Journey, and mythic quests. Therefore, in answer to your question, one should expect to find commonalities between the Popol Vuh and other creation texts.

As part of the Christian campaign to convert and colonize the Maya peoples and their lands, the Popol Vuh barely survived the Spaniards’ attempt to burn every last Mayan text. Early on, based on general reading, I assumed that Christian narratives such as the Virgin Mother had been added to the Popol Vuh by Fr. Ximenez who finished translating it in 1703. However, after wrestling with this issue for several months and reading conflicting opinions, I decided that Ximenez (whose translation of a now-lost text is our only source) was protecting the spiritual essence of the Popol Vuh for future generations. I think that he avoided injecting his own beliefs. If so, Ximenez had to be cautious since merely translating the Maya codex was risky enough, and any outward advocacy for Maya beliefs on the part of Ximenez would be grounds for religious heresy. Keeping all this in mind, let’s examine the textual evidence.

Ximenez indicates on the title page of the Popol Vuh that he is writing: “for the convenience of ministers of the Holy Gospel.”

About six sentences from the start, one finds a second Christian attestation. Ximenez writes (Christenson): “This account we shall now write under the law of God and Christianity.”

Ximenez’ statements suggest that he is writing from a position of Christian faith and might even reflect an earnest fusion of Maya and Christian beliefs occurring at that time. As well, this might be Ximinez’s strategic attempt to thwart complete suppression of the manuscript by Catholic authorities. Tellingly, Ximenez was silent as to whether his translation was from an oral or written source, perhaps indicating a desire to protect his source from discovery and persecution.

More importantly, there are no other Christian references in the text. None. Nada. Zilch. Instead, as I will discuss, Ximenez proceeds to present an ancient Maya narrative. All the other supposed Christian influences present in the Popol Vuh are better ascribed to the “natural” presence of universal religious archetypes that Joseph Campbell has described. Universal archetypes and symbols common to both Maya and Christian cosmology include virgin birth, tree of life, resurrection, and dark demons. Some missionaries used these examples during conversion to imply that the Maya religion had already groped towards an incomplete grasp of Christianity. Such commonalities were useful in conversations and sermons whose goal was Christian conversion.

However, the manner in which virgin birth, fish, tree of life, resurrection, and dark demons are portrayed in the Popol Vuh is not even remotely Christian. For example, the virgin Lady Maiden Blood is not impregnated by a Supreme entity. Rather, she touches a fruit from a tree that holds the dying spirit of the Hero Twins’ father. The Tree of Life is not a cross, but extends up, down, and horizontally in the four cardinal directions. The Maya resurrection is not that of a dead body in a cave, but results from ground up bone fragments forming catfish and then transfiguring into orphans. As well, readers will see that these archetypes and symbols fit so seamlessly and intricately into the complex narrative flow of the Popol Vuh that it does not seem plausible that they were fabricated by Ximenez to appease Christian interests.

Finally, these particular Maya elements predate the arrival of European influence as evidenced in pre-Columbian pottery, codexes, and friezes. The Twins as fish date back to pre-Columbian pottery. The tree of life is depicted on a 7th century Palenque tomb. The virgin mother is depicted in the Dresden codex circa 1100. Therefore, the pre-Columbian existence of these so-called Christian influences present nearly irrefutable evidence that they are original to the text.. Therefore, it seems to me that Ximenez and his source were conscientious about preserving and not Westernizing the Maya narrative cosmology of the Popol Vuh. As well, Ximenez’ translation lay undiscovered for another century and a half until it was found appended to a grammar text that he had also written. He may have been hiding his work in the hope that it would be discovered in a time when society would be more accepting of its survival. I like to think that Ximenez knew what he was doing—he was playing the long game.

As I read the text, I found myself thinking about the concept of the palimpsest, particularly as your own experiences with the text and Mayan culture became a part of the way readers interacted with the story. How do you think the idea of the palimpsest applies to the Popol Vuh and Mayan culture?

Palimpsest is a fun word that we poets (Camille-Yvette and I are both poets!) like to wave around. A palimpsest is a papyrus or parchment that has been written on more than once, with the earlier writing incompletely scraped off or erased. It was the best metaphor I could find for the layers of time, language, and uncertainty that lie between the modern reader and the original text. The centuries of erasure and “scribbling over” result in an irreconcilable distance between the original Ur-text and its altered current form.

So it is with the Popol Vuh where our only source is the 1703 manuscript written in the hand of Fr. Ximenez, now housed at the Newberry Library in Chicago and open to visitors. For readers in Chicago, I recommend calling to arrange viewing of the Popol Vuh along with the later illustrations of Diego Rivera, as well as the originals of our book illustrations by Leonard Greco. Will Hansen (Curator of Americana) and Analú López (Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator of American Indian and Indigenous Studies) at The Newberry have been kind enough to add our version of the Popol Vuh to their library collection. As America’s oldest surviving poem,the Popol Vuh rightfully deserves to be the first entry in any survey of American literature.

Ximenez’s translation of a lost version of the Popol Vuh derives from what was once a written hieroglyphic document. Ximenez (fluent in native K’ichi’) first recorded the Popol Vuh in phonetic Latin based upon the sounds of the K’ichi’ words, and then later translated the Mayan phonemes into Spanish. Eventually his work was rendered into several English translations. I was aware of Ximenez’s methods when I embarked upon my own adventure. By reading translated sources from circa 1600s and drawing from my decade of annual travel to Central America as a volunteer surgeon, I was able to piece together the foods, insects, birds, culture, and other features of Maya life. I used these to fill in the daily details of the Hero Twins’ lives, trying to raise the past into sharper relief for the modern reader. Reading all the English translations provided a multifaceted and nuanced view of the Spanish original.

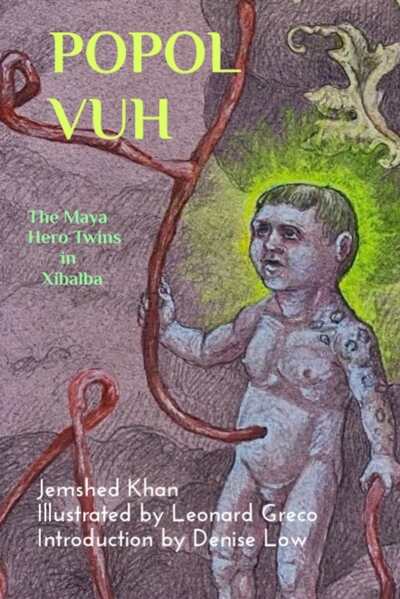

Unlike other translators, our version relies heavily on full color illustrations by Leonard Greco. Greco used Baroque illustration methods from the 1600s. Beginning with the cover, his neobaroque images are a sight to behold, accompanying each verse and imparting a dreamy otherworldly feel reminiscent of Blake. The purpose of these images is twofold: first as a visual aid through the many twists and turns of the plot, and second, they act as glyphs, conveying a meaning beyond text. They are part of the palimpsest. Despite immense barriers between the modern reader and the original meaning, I wanted the reader to understand the barriers and fuzziness and loss of meaning, such that modern readers feel empowered to engage in their own interpretation and experience. This goal was aided by layering pre-Columbian, 1600s Spanish, and contemporary narratives.

What made it so important to you to bookend the translated portion of the text with poems about your own life and then the poem about the experience of the day keeper? How do they help to contextualize the text for the reader?

The book-ending occurred organically as the text came together. At first, I was just planning on a chapbook of haphazard poems loosely drawn from the Popol Vuh and my own experiences. I managed to interest artist Leonard Greco in the incipient project. As the work progressed, it became evident that a much more comprehensive approach was in order. This evolved into a book length project which was more than Leonard had signed up for. He was quite gracious in producing additional illustrations for what had become an expansive and more ambitious undertaking. As a result, the overall structure of the book took on increasing importance.

Jamaica’s Poet Laureate Kwame Dawes strongly encouraged me to interject my own personality and experience into the work. He provided some African diaspora templates (Masks, by Kamau Braithwaite, Omeros, by Derek Wolcott). His advice was extremely important in my realization that, as an outsider, my own experiences should bracket the Twins’ story rather than inhabit it. I wanted to stay true and respectful of the original narrative and not interrupt its spiritual energy. Therefore, I wrote a preface where I outlined my Honduran activities and began with five personal poems arising from my Mesoamerican adventures. As well, I asked Kansas Poet-Laureate Denise Low to write an introduction as she had taught the Popol Vuh for many years.

Another major part of the overall structure, an historical section, was driven by recognition that many readers have never even heard of the Popol Vuh and would enjoy learning the strange history of its loss and rediscovery. Political considerations also play a role since the Maya peoples have been suppressed for centuries and divided by national boundaries. They are now strengthening their cultural identity through written language, stories, history, and educational systems. Also, much of the US Hispanic diaspora has lost touch with their ancestral beliefs and identity which were largely supplanted by Christian beliefs, the imposition of national identity, and the struggle to assimilate. We hope readers will enjoy learning the history of the Popol Vuh and its relationship to ancient and contemporary Maya culture. The most rewarding comments I receive are from second and third generation US Hispanics thankful to reconnect with their ancestral culture. They value placing the epic narrative within a larger cultural and historic context.

For personal context, I have been visiting Honduras for over a decade; performing volunteer surgery in El Progresso and then taking the Hedman Alas bus to the ancient town of Copan Ruinas. The Maya ruins there are magnificent, though not as grand as Chechen Itza. Naturally, I began to explore the area and eventually bought a small farm beside the Rio Copan. Therefore, I had personal experience and writings to draw from. Not only that, but I saw firsthand how the Maya, their culture, language, land, religion, and ancient cities are still present and vital to the day-to-day economy of the area. I wanted the reader to understand that both the Popol Vuh and Maya culture had survived and were alive.

The question was how to incorporate these ideas into the work without detracting from the spiritual text? I looked to Ximenez who prefaced the Popol Vuh with his own beliefs. This allowed him to get them out of the way and get down to the real work of preserving the meaning for future generations. The English translations all have some introductory remarks, as well. I loosely modeled this book after them, including scholarly touches such as a glossary and bibliography so that the book would be a suitable entry to a broad group of readers such as students, scholars, Meso-American diaspora, etc.

Personal history aside, I also sought to clarify my emotional relationship to the text, especially since the narrative was writing itself and I was literally waking up at night to channel powerful voices and characters emanating from the text. Many other translators of the Popol Vuh have reported similar encounters with spiritual forces. These are discussed later in the interview.

The book closes with two poems, the first of which empathizes with the original Maya scribes who were persecuted as the Spaniards systematically eradicated Maya writing and culture. Indeed, many writers still walk the cultural tightrope between relevance and censure. The second poem recounts a 4:00 AM trek I took into the Maya highlands to catch the equinoctial sun rising above an ancient carved Maya stella. After sunrise, the guide and I were like the Twins embarking on a cyclical journey back to the town of Copan Ruinas.

How do you see the Popol Vuh as interacting with other origin texts?

The Twins’ portion of the Popol Vuh is similar to heroic epics such as the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh and the Homeric epics of the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Popol Vuh is polytheistic when compared to the three Abrahamic religions. If we dig further, the Popol Vuh is less prescriptive, paternalist, specist, and authoritarian than monotheistic texts. For example, animals and even insects have agency and voice. As well, the Twins and underworld Lords are fallible entities that symbolize the duality of light/darkness, above/below ground agrarian crop cycles, seasons, and fertility. The underworld Lords are not so much evil as they are overbearing in demanding human sacrifice.

Indeed, the purpose of the Twins’ underworld journey is not to destroy and cast out the underworld demons, rather it is to establish a balance between the two worlds. In Christian cosmology, Jesus’ death provides a sacrificial and substitutional atonement for human sin, whereas in the Maya cosmology, the Twins confront the inherent unfairness of human blood sacrifice as a form of appeasement. In both systems, humans are relieved of the burden of ritual blood sacrifice, but only one system confronts the immorality of human blood sacrifice.

Like the Christian Bible, Quran, Jewish Tanakh, Hindu Puranas, etc., the Popol Vuh has creation narratives regarding human presence. Unlike Taoism, Buddhism, and other major religions, the Popol Vuh is light on moral teachings or philosophical precepts. Perhaps these were contained in the other Maya texts that were burned in 1562 by Friar Diego de Landa? We will never know. What I surmise is that most Maya human sacrifices involved prisoners of war or criminals, indicating a legal and judicial system of capital punishment rather than ritual appeasement.

All of the world’s origin texts offer their own narratives and beneficial advice. I see the Popol Vuh as being particularly balanced and applicable to modern times with regards to recognizing the agency and worth of all life forms, agrarian philosophy, and confronting exploitive systems The Popol Vuh reinforces cooperative human behavior and recognizes basic human emotion, motives, and behaviors. Unlike many spiritual narratives, the Popol Vuh presents strong female role models that are central characters in many ways. For all these reasons, the Popol Vuh seems to avoid many of the patriarchal shortcomings of other foundational religious texts.

Why is the story of the Hero Twins so important in thinking about Mayan culture?

From a historical perspective, The Maya Twins embody many aspects of ancient Maya culture. The Twins represent the Sun and Moon, day and night, warrior culture, jungle travel, multigenerational families, clearing land and planting crops, and so many other aspects of Maya life. The Popol Vuh illuminates many aspects of surviving Maya ruins including the ball parks, layered pyramids with their subterranean passages, sacrificial altars, seasonal rituals, and rulership.

For contemporary Maya peoples, the Hero Twins’ journey is an inspiring narrative in their struggle to reestablish and strengthen their own agency and identity. Especially in the face of national interests, land rights, and foreign corporate interests. Although the Maya are supposedly guaranteed rights to their indigenous lands, many of these properties have been titled in other names, including my farm which rests upon land that is by rights, indigenous.

Surprising differences emerge when I compared the Abrahamic twins Jacob and Esau with the Maya Hero Twins. According to Genesis, the Abrahamic twins are engaged in a zero-sum winner-take-all contest to obtain their father’s birthright and property. The contest is resolved through dishonesty and trickery, but results in the more competent brother taking charge and ownership. By comparison, the Maya Hero Twins also engage in deception and trickery, but they work cooperatively with each other and with other animals, insects, and gods to overcome the underworld demons. The competition between the Twins and the underworld Lords centers around a ritual ballgame Pok-ol-pok. Such stone ball courts are still scattered across meso-America and were central to many seasonal rituals. The contest is spiritual and cosmic rather than over resources.

In some ways the contrasts between the Abrahamic and Maya beliefs reflect pastoral versus agrarian societies. Live sacrifice, livestock, grazing rights, and water resources are central to pastoral religions whereas cooperative behavior and seasonal cycles are central to agrarian societies. It is interesting to speculate that these contrasting ancient twin archetypes still seem to manifest in their modern counterparts of predatory capitalism vs the collective tendencies of indigenous meso-American populations.

You noted that you particularly wanted to amplify the voices of the mother and the grandmother in your version of the text. Why was that vital for you and how do you think it enhances our understanding of the text?

We have all noticed that most of the world’s foundational texts give short shrift to women’s lives. Certainly, the work of Joseph Campbell has been criticized for his focus on male narratives and de-emphasis of female archetypes. The Popol Vuh offers an opportunity to showcase female archetypes in foundational literature, especially since the Maya clearly emphasized and respected multigeneration maternal and grandmother roles. It would be negligent to minimize these roles or to ignore the emotional aspects of their traumas and joys which should resonate with all readers.

Though the Hero Twins are major characters, they do not spring de novo into the epic. Rather, they are conceived, birthed, and raised by powerful and somewhat solitary female figures who must survive without male partners. These strong well-developed female personalities shine through the Popol Vuh. For example, the Twins’ mother, Maiden Lady Blood, is daughter of an underworld Lord. When it is discovered that she is pregnant and there is no father, her punishment is to be banished and her heart is to be removed by a war owl. How can one not empathize with such a mother and her circumstances? She outwits the Lords, and then must convince her Twins’ grandmother to take her in. The grandmother is skeptical and wary and this all shines through in Ximenez’ translation. One sees the inner life and longings of the grandmother who has already lost a son to the underworld, and the mother who must protect her unborn sons. These independent female characters embody agency, collaboration, resolve, and survival. The multigenerational female arc and powerful emotional pull of the Popol Vuh are qualities that surpass other archetypal male-hero epics.

In Denise Low’s introduction, she says that this is an interpretation rather than a transcription. Why does that feel like an important distinction and what has that allowed you to do as a writer?

Denise Low is a brilliant polymath, poet-laureate, and friend who has taught the Popol Vuh at the university level, so I take her advice seriously. As well, she has a scholar’s understanding of the difficulties of translation. So, let’s dive in! Codexes contain hieroglyphic sequences and panels rather than purely linear text. The Mayan scribes who preached from these documents had great latitude in converting the meanings of hieroglyphs into rousing spoken sermons. Therefore, unlike pure translations, our work emphasizes the traditional use of a Maya codex as an inspirational hieroglyphic text that generates a secondary impassioned narrative.

As an author my goal was to present the Popol Vuh as a gripping epic adventure that brims with all the life, drama, spirituality, and archetypal character that are inherent to the text. We stayed fairly true to the original text, but I felt that the existing scholarly translations were constrained by the desire for academic fidelity. Therefore, they necessarily diluted the underlying spirituality and excitement of the Popol Vuh. However, even in translation, the Popol Vuh brims with spiritual force precisely because that was its original purpose - to communicate spiritual precepts. The survival of this “embedded function” accounts for other translator’s comments about experiencing spiritual forces. Mostly, they did not succumb to such forces, hence, their reading audience was limited to those interested in the text itself rather than spiritual elements emanating from the text. Leonard and I both discovered independently that we were channeling and engaging such forces at a distance. We believe that these voices emanate from the narrative. As such, our approach honors and reifies the original doctrinal purpose of the Popol Vuh. We hope that the result is that the narrative and spiritual overtones of the Popol Vuh will be more widely recognized, enjoyed and appreciated.

In closing, I was fortunate to collaborate with illustrator Leonard Greco who created a marvelous and inspired image for every poem. Our shared vision is based on tapping into the Popol Vuh’s underlying narrative arc as well as its spiritual intent and sentiment. As author and artist, that choice resulted in encounters with powerful ancient voices. Now that all is said and done, both of us are happy to be returned to the world of the living and our pre-existing belief systems. We believe that the Popol Vuh is due for a resurgence and hope our work might contribute in some small but long-lasting way.

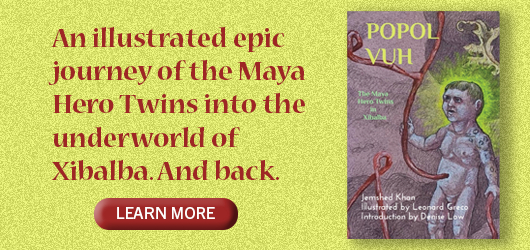

Popol Vuh

The Maya Hero Twins in Xibalba

Jemshed Khan

Leonard Greco (Illustrator)

Blurb (Jul 1, 2025)

Clarion Rating: 4 out of 5

Popol Vuh is an immersive, inventive reinterpretation of a Mayan creation myth.

Jemshed Khan reengages the Mayan creation myth Popol Vuh by reimagining the Hero Twins and their tumultuous time in the underworld.

Complemented by surreal images, this book is a work of layered narrative poetry in which the past and present coexist. In contemporary times, a thirteen-year-old (modeled after Khan) in an oil town along the Persian Gulf finds a scepter with a replicated Mayan carving on it. The discovery sparks a lifelong interest in Mayan culture, seen in poems like “Kukulcan 1982,” in which a guard is bribed to allow Khan entrance to the grounds of the pyramid at Chichén Itzá. There, he imagines Mayan warriors superimposed over the present and hears “their spirits ask, // Who shall journey to the underworld / and raise us from the dead? / Who will fight for this sacred land?” Indeed, the serendipity and synchronicity of the boy finding the scepter becomes a part of the power and mythos of the Popol Vuh itself.

The book’s interpretation of the Mayan creation myth is quite direct, and it centers the book most. In it, the Hero Twins—born of Maiden Lady Blood and a slain warrior whose decapitated head merged with a dead calabash tree and brought it back to life—are brash and crafty. They trick their grandmother into believing they are farming but instead play pokolpok, a Mayan ball game. When a bid for a competition on the court comes from the Underworld, the arrogant twins rush to follow the owls, convinced they will beat Lord One Death and take revenge. Unimagined perils await them instead, though their relationship helps them survive.

The poems related to the creation myth are character focused; though tying into hero and villain archetypes, they build on the sympathetic connection between the twins and the ways their relationship strengthens them. They possess warrior skills and fantastical magic. In active scenes, they name each of the seven lords of the underworld and survive beheading. Through it all, they maintain faith in each other and the plans they have hatched.

Most of the poems articulate a particular trial, and the short lines and vivid descriptions have an immersive quality. In surreal settings, flora and fauna are lethal and insects act as informants and assassins. In one poem, a twin manifests mosquitoes from a single leg hair; in another, “screeching snatch-bats / careen through the pitch dark, / ready to tear the boys apart.” Musicality is achieved via subtle rhymes and rhythms.

The twins’ trials conclude with a strange, breathless series of tumbling actions, wherein reversals of fortunes abound. And the book’s final section catapults forward to 1520, when the Mayan culture starts to fall to the Spanish and the Day Keeper works in silence and secret to keep his culture alive, reflecting the timelessness of the central tale: “Our books burned, / our temples looted, / gods transmuted, / but fire and pox / do not silence us.”

This personalized, playful retelling of Popol Vuh, a cultural touchstone, reinterprets the Hero Twins’ rollicking descent into the underworld.

Reviewed by Camille-Yvette Welsch

October 23, 2025

Camille-Yvette Welsch