Meet Author Patty Krawec at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds

Reviewer Jennifer Maveety Interviews Patty Krawec, Author of Bad Indians Book Club: Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds

Bad Indians don’t play along when you expect them to think and act in a certain way. Bad Indians refuse to let prevailing narratives replace the worldview that factually represents their land and people. Bad Indians, when given the chance, offer revelatory ways of thinking about a world you assumed you understood.

Today, we’re thrilled to connect with one of those intrepid Ojibwe authors, Patty Krawec, author of Bad Indians Book Club, a brilliant exploration of the books and authors offering new ways of seeing and thinking about the world from an Indigenous perspective. The book earned a glowing review from Jennifer Maveety in Foreword’s September/October issue and we quickly connected the two for a thoughtful conversation.

You include your own fiction in this book. What was your intention behind including the tales of Kwe into a book primarily focused on literary criticism, and what do you think it adds to the book overall?

I had promised my publisher a book that was about reading broadly, but also with the thread of Deer Woman who is a figure that exists in various ways across many cultures around the world. I wanted to include her in some capacity because one of the things about her story is that it changes over time and location which is a central idea in the book. The things that marginalized writers think about vary and shift according to their location, so she seemed the perfect companion to this exploration of the many worlds that become available to us when we read widely and intentionally.

The idea of using fiction to do this came from reading Chelsea Vowel’s Buffalo is the New Buffalo, a collection of short stories in which each story is accompanied by a brief essay about the story and the socio-political issue that she is considering through that story. There is one in particular where she tells the same story in four different forms: hint fiction (under 25 words), micro fiction (under 300 words), flash fiction (under 1,000 words), and a more conventional short story. The discipline of telling a complete story in 1000 words that both stands alone and connects easily with the other stories was an intriguing challenge. Bad Indians Book Club emphasizes the broad range of marginalized literatures organized around themes and this serialized flash fiction helps ground the book in the Anishinaabe world. Vowel also points out that flash fiction invites the readers into world building because there is much that is unsaid. I would be very curious to know how readers imagine the story around these brief glimpses.

Kwe experienced a profound change and is trying to figure out how she belongs in the world, what her role or position is now that everything about her is different. Her tendency to run puts her in contact with a variety of places and people so that when she finally does go home she is in a much better place to understand and accept what and who she is within a much larger context. Reading helps us to have that kind of contact with a wide variety of places and people if we do it intentionally, with a willingness to challenge our assumptions. Reading intentionally challenges us the way that the sweatlodge challenges her, it reveals things about us and what we think of as normal or inevitable. That was something I played with by changing the tense and narrator, to move the reader around and in one section, putting the reader into the story by using the second person. It was a lot of fun and I would like to return to her and perhaps give her an entire novel to see what she gets up to.

During your research, was the selection process challenging? How did you decide which fiction and nonfiction works and authors to include when analyzing difficult topics?

The majority of it came from my own bookshelf, which is largely filled with books that I had come across through conversations on social media or podcasts that I listen to. In one of his interviews on the Movement Memos podcast, author and activist Dean Spade said that you should never be the most radical person in the room, to which I would add, or the smartest. I seek out people who are both smarter and more radical than I am in their desire to build a more just world because of what they can teach me, how they can challenge me. We’re often afraid of the word radical, but it simply means to pull something out by its roots, and any gardener will tell you that with some particularly invasive weeds if you don’t do that they’ll overrun your garden no matter how many times you cut them down.

Having a podcast is a great way to invite people who make interesting or thought provoking statements into conversation and get deeper into them and for five years my friend Kerry and I had loads of those conversations on our podcast Medicine for the Resistance where I often say that people can listen to us learning in real time. Those people write and recommend books, which filled my bookshelf because of course I would read things published or recommended by people who had become digital friends and whose judgement on various topics I had come to trust. So, in a sense, the book also reflects my social media life in those years and the people I came in contact with through that medium.

The format of the original list I made in response to a friend’s question about recommending a book or two also played a significant role. They asked in November, so that got me thinking about a new year’s resolution based around books, which meant thinking about what books tied into each month. Reading towards or against holidays or seasonal activities was easy, months where there wasn’t anything obvious was more challenging.

People often have a handful of Indigenous writers that they rely on for everything, and it seems like we are mostly relied on for ecological writing which is just a contemporary version of the noble savage trope. I wanted to avoid that, so I recommended several books on each topic because marginalized writers come at things from so many different ways, which is also where the second part of the book’s title comes from: Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds. The idea of a world where many worlds can coexist comes from the Zapatistas and it is a perspective I value. I grew up in a belief system that thought it had the answer for everybody, an answer that had to be imposed on people whether they liked it or not. The Anishinaabe worldview, much like the Zapatistas, invites us into a much different set of relationships: it invites us into a world where many worlds can co-exist.

Another factor in book choices came in the second month when we talked about history. Author Tiya Miles brought up the gaps in Native Studies where Black people should be, and the gaps in Black studies where Native people should be. From that moment I began looking deliberately for the gaps, for what was missing and then looked for authors who could fill those gaps beyond my initial intention to focus on writers who are Indigenous to the Americas. Although the original list and the podcast series focused on writers who are Indigenous to North America, it quickly expanded to a more global perspective and Bad Indians Book Club expanded that vision further. I still do that when I’m wandering a bookstore, stopping at a section I don’t know very much about and then looking for books to read.

In discussing your personal book club(s), you cover topics ranging from gender identities to language. Are there any conversations that have been more challenging than others to discuss in a group? How has race, culture, and gender offered new angles to these discussions and how did that influence your writing?

Writing about and having the panel discussion about gender, we called it “Refusing Patriarchy,” was challenging for me because I am a married cis woman. Married to the same person for forty years now. And I grew up in the evangelical church. I have queer and trans friends and family members, so the challenging part was not whether or not I should have the conversation but how I participated in it because much of that conversation was about a community I am not part of and for many years held beliefs that misrepresented them. For some that might be a motivator to stay out of it, making the excuse that it is not your lane, just focus on feminism, but I think that is a good reason to engage in those hard conversations. To approach them with humility and curiosity, and the willingness to hear things we don’t want to hear, to recognize our defensiveness as a barrier and push through that discomfort rather than argue. We don’t know how to have these conversations, how to listen without offering advice, or how to hear things that might be challenging or make us feel bad about ourselves and our own choices or participation in things.

I curated the groups carefully, something that we’re not generally able to do in our day to day lives, but I think we can be more intentional about our friendships and how we meet people or develop relationships. We don’t have a lot of third places in our lives, those places between work and home, where we would come across people who are in different generations or social identities, and our society is moving further away from having third spaces that are free to access; so much of what we do have is inaccessible because of where they are or the cost associated with them which is one reason why I’m always happy to talk with and support libraries. They are one of the few places left that we can go year round that doesn’t charge admission or require you to buy something. So it’s worth asking ourselves, am I even going to places where I could make friends with people who aren’t like me? How can I be part of creating a space like that? I think that having the conversations in podcast format helped to model for others how they can have conversations in their own circles, particularly when guests push back on something I said. This goes back to the awareness of gaps, what don’t I know? How can I develop better knowledge? And in the case of topics that we may be uncomfortable with or find difficult, reading can be extremely helpful by demystifying it and exposing us to a variety of perspectives outside of our comfort zone before we even start building relationships, a kind of 101 as long as we remember that people aren’t like the books we read.

What advice would you give to groups who want to form their own book clubs but aren’t sure where to start?

This book club started with a question and a response that quickly spiralled out of control. I would start there, with a question. What are people curious about? What knowledge is needed right now? Because there are two basic kinds of book clubs or reading groups: feel good wine clubs and those more geared towards educating. Both are great, they just serve different purposes but either way it begins with curiosity and then finding people who are also curious about that topic. Start with curiosity and then think about the best way for your group to find an answer to that question that comes from a place you might not normally look to for answers.

Political education is so important right now, we’re having all kinds of thoughts and reactions about profound political and military events taking place but without a solid understanding of what brought us here. We talk about the importance of relationships, and I wholeheartedly agree with that, but relationships without any kind of analysis about power imbalances and the social realities that different people experience can be counter productive. I know people who have Palestinian friends but still believe that Israel is in the right. We all know people who have [racialized minority] friends and think that means they can’t be racist. I think book clubs fill a very important space in our society both for connection and education in ways that other structures don’t allow for. Reading groups always have. Books require a time investment from the author and the reader, conversations extend that time and expand our understanding with other perspectives on the same material. That changes us.

Your title Bad Indians expresses how you feel aligned with Native Americans who are devoted towards upending detrimental hierarchical structures and demanding promises be kept by governmental systems. How do you think this identity shaped the references you chose to back up your theses in your book?

It’s more like I wrote a book about how marginalized writers help us upend these structures, and then gave the name “Bad Indians” to all of these writers.

One day while feeling a bit cranky I added a line about being a “bad Indian.” My editor loved the line and commented that it would make a great title which put me in a bit of a quandary. I hadn’t written a book about “bad Indians” and now I needed to go back through the manuscript again to define the term and then connect it with my various themes. Who are Bad Indians, why do we care about all these genres of books? What might we think about the land, gender, the self-reflection of memoir? That also sent me looking for authors who were particularly confrontational about things that need confronting, like Klee Benally who introduced me to the idea of “hostile spaces” as a counter to “safe spaces.” Often when we talk about “safe spaces” they are safe for everybody but without that analysis of power and social realities I mentioned earlier, and as a result they quickly become unsafe spaces for marginalized people. Benally suggests spaces that create safety by being hostile to oppressive or dehumanizing ideas and that’s where the title for the chapter about gender came from: us but not you. While I was kicking around title ideas based on “Bad Indians,” somebody asked if I had read Deb Miranda’s book Bad Indian, and I had not. Reading her book was profoundly helpful in connecting this idea with the material itself, particularly in her “Novena to Bad Indians” that I reference near the beginning of the introduction.

Your book includes an abundance of Ojibwe stories and history, and every chapter includes Ojibwemowin. When you began writing this book, did you plan to include so many Ojibwe teachings or was this something that became more important during the writing process? What do you feel these additions do to help strengthen the book?

It keeps me grounded. Lee Francis IV gave me some fantastic advice as an early reader for Becoming Kin that combined with a critique of Becoming Kin in an otherwise positive review. Lee said that the book needed more of my own story, why these things mattered to me and the reviewer expressed disappointment that the book wasn’t more firmly grounded in my own Anishinaabe land. I did add more of myself to Becoming Kin after Lee’s feedback, but clearly it needed more grounding, not just in my personal connection but also with the larger presence of the Anishinaabe. Our introductions identify ourselves, our clans, and our nations, and including our own stories and language helps me to locate the book within those things.

More to this point, this is a book written by an Anishinaabekwe living in Canada, so you’ll probably notice the Canadian spelling as well. For this I have to credit Dr. Max Liboiron who wrote Pollution is Colonialism and commented that words and spelling matters because language comes from place. The Ojibwe language and stories, the Canadian spelling, all of that spells out my specific location which shapes my perspective. Land relations, the story of how we came to the place where we are living and working from, is a key part of this book and why everybody I talk about is grounded in some way to their own land relation. The places we read and write from matter because they shape how we engage with ideas, and often they shape which ideas we are even exposed to.

I begin my Bad Indians Book Club: Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds with two epigraphs about the importance of grounding ourselves in our own land relations and then building solidarities across the barriers created by colonialism. The first is from Natalie Diaz, a Mojave/Akimel/O’odham poet who said, “It’s not about blood and it never has been. It’s about how you arrive and build a relationship with the land you’re on. And once you’re there, it’s also about how you receive others.” [1] David Truer, an Ojibwe writer from the White Earth reservation wrote that “Other nations take these things into account, and in doing so they reinforce something we, with our fixation on blood, have forgotten: bending to a common purpose is more important than arising from a common place.” [2]

We stay who we are, the children of our ancestors connected to specific places and times and political realities. That means thinking clearly about how each of us got here, who was pushed aside because these western countries like to pride themselves on that second part, a dubious claim to the fraught history of “welcoming others” but without any critical reflection on how they arrived and built a relationship with the land or the political choices made about who was welcomed and who wasn’t. Without that critical reflection, the best we can hope for is a kinder and more inclusive settler colonialism which will inevitably fail because the foundation is rotten.

Once we have done the work of reflecting on who we are, returning to ourselves, we can transcend those social, racial, and political identities that are too often framed as barriers and find those who are bending with us towards a common purpose. We bend together, but stay who we are, because who we are matters. Anishinaabe governance offers an interesting model for this. We are a patrilineal society with a clan system so the children take the clan of their father. But when a woman marries she keeps her own clan, she doesn’t become part of her husband’s clan because she stays who she is. She retains those relationships and histories attached to her own family and clan. We stay who we are, but we build relationships with others outside of our group. I heard a rabbi talk last year in the context of Palestinian solidarity about the importance of forming coalitions rather than just becoming allies which is a very individual approach lending itself to white saviourism. In his model we stay who we are, educate our own community, work towards justice for our own community, but also understand that communities are connected and so we come together periodically to address broader injustice. I thought this was beautiful, coalitions instead of allies. It focuses on the strengths and needs of each of our communities while also prioritizing the needs of the most vulnerable in that moment, being accountable to the most vulnerable in that moment.

For me, this is the key to our survival as a species. To think and organize transnationally alongside those with whom we bend towards a common purpose, and to think beyond the rigid binaries and borders that shape the western world because even thinking about our various communities is fraught. We talk about the Indigenous community, the Black community, the Queer community, etc., as if they were not only clearly boundaried from each other but also somehow the same internally. Within each of our broad communities exists a wide range of diversity in belief and politics, in our relationship to what may be understood as traditional beliefs as well as new beliefs, in our ability to access and mobilize external power structures. We contain multitudes, and we don’t always bend towards a common purpose even if we share ancestry and place. Our communities exist in broad overlapping shapes and our politics, the common goals towards which we bend, is often shaped by how and in what context we overlap with varying identities or ways or being in the world. This is the principle of intersectionality and identity politics described by the Combahee River Collective and its intellectual descendants. It is also a fundamental principle of Anishinaabe governance. Our relationships are rooted in bending towards a common purpose that also recognizes where we are bending from and interrogates how that bending is shaped and constrained by the world around us.

So using Anishinaabe language and stories is a way of keeping myself grounded so that I and the readers remember where I am bending from, and hopefully it encourages readers to do the same, encourages them to see how their own stories or language might connect and how together we can build something worth building because if there’s one thing that Bad Indians know, it’s that there is no single world to which we must all conform. There are a thousand worlds waiting to be born.

[1] Dahr Jamail and Stan Rushworth, We Are the Middle of Forever, The New Press, 2022 p 300

[2] Truer, David. For Indian Tribes, Blood Shouldn’t Be Everything. New York Times, December 21, 2011

What is one thing you would say to younger generations of Bad Indians to express the importance of reading as they grow?

When I was angry about a particular incident of injustice, it provoked me to write an article that was published by Sojourners Magazine. I’ve always been a reader, but I had never thought of myself as a writer and in that moment I felt helpless to address the incident. I could talk to the person involved, and I eventually did, but that wouldn’t do anything about the broader society and the context in which this happened. It wouldn’t address or confront all the people who laughed or otherwise shared the opinion of this person. Writing allowed me to be part of the broader conversation and instead of changing one mind (which sadly, I did not) I was able to challenge many people and over the years, because that article lead directly to Becoming Kin which lead directly to Bad Indians Book Club, I have heard from many many people about the impact that I had on them and the ways that changed them. They told me about the actions that this book provoked them to take in the places where they worked or studied or worshipped.

Becoming Kin has been used as a classroom textbook in high schools, colleges, and universities. Hopefully, Bad Indians Book Club will also find that kind of actively engaged audience because I think it gets at many of the same issues and more in a much broader way that will appeal to readers beyond those interested in history. And I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish any of that without reading, without reading widely, and consciously choosing material that would challenge me in some way. There is so much that is worth being angry about right now, and writing is a powerful way to channel that anger in ways that push us towards a more just world but if you are not widely read then you have limited resources from which to write or think. I want to be careful with this, because I don’t want people to think I mean you have to read or listen to books and only books. For all that, Bad Indians Book Club is about books, it is also about traditional stories, movies, and poetry. My book launch includes an art exhibit and music because those are also ways that we tell stories. You have to seek out and pay attention to stories wherever you find them, particularly if they are from a community that is unfamiliar with you.

Another thing I would remind them is that banned books are banned by people, and those people are organized in specific places where they get to make those decisions. There are a lot of books being banned across the US and in Canada so I would encourage them to not only read from these growing lists but to get involved in the places where those decisions are being made. It’s not enough to post pictures on social media about how you read this book that is banned here or there, at some point people have to get onto these boards where the decisions about which books to put on the shelves and which to take off are being made. They can do this in their schools, local bookstores, and libraries. Look critically at the shelves. Who is missing, and why. What are the gaps? Find a way to fill them. And the best place to make these arguments is to read widely so that you can recognize the gaps. That’s why the first rule of Bad Indians Book Club is to always carry a book, no exceptions.

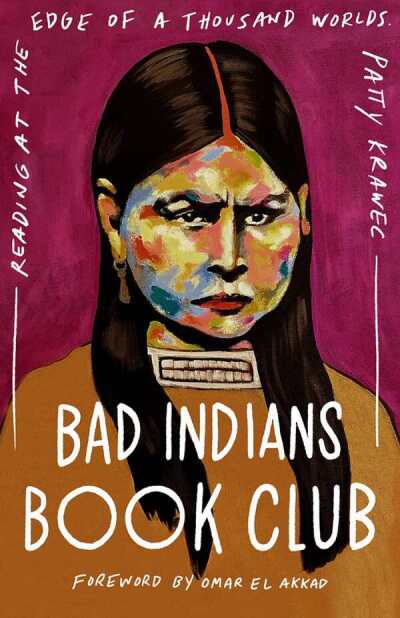

Bad Indians Book Club

Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds

Patty Krawec

Broadleaf Books (Sep 16, 2025)

Bad Indians Book Club, Patty Krawec’s compelling work of literary criticism, centers stories written by marginalized people.

Focused on Indigenous culture and showing that reading is essential and that addressing the hard truths of history is a necessity, this is a book about colonization, community, and their ties to, and reflections in, modern and historical literature. It examines works including Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower and a book about the Salem witch trials. Science, traditional medicine, and Anishinaabe origin stories are incorporated in a flowing and accessible manner, while challenging subjects including race and historical trauma are handled in a reflective, careful way.

Each essay is multidisciplinary. In one, patriarchy and gender roles are discussed; Krawec digs into the “us but not you” concept and includes references to alternative forms of feminism, referencing indigenísta feminism and the kyriarchy. Historical factors including enslavement are untangled amid references to media like Reservation Dogs.

Stories about Kwe, a girl whose body merges with that of a fawn, are included after each essay, too. As Kwe navigates colonization, she is pushed into traumatic situations, like an attempted assault outside her place of work. After an unexpected death is revealed, Kwe reflects: “The gunpowder and violence I associated with it crowded my memories, a trail of smoke leading to an old story.” And throughout, Krawec interweaves her personal stories with those of fellow authors to encourage reassessments of normalized but faulty beliefs, as with the idea of “Bad Indians” who don’t follow the path of colonization.

A detailed and exploratory work of literary criticism, Bad Indians Book Club examines culture and colonization through a multitude of written works.

Reviewed by Jennifer Maveety

September / October 2025

Jennifer Maveety