Inside the Cuban American Diaspora

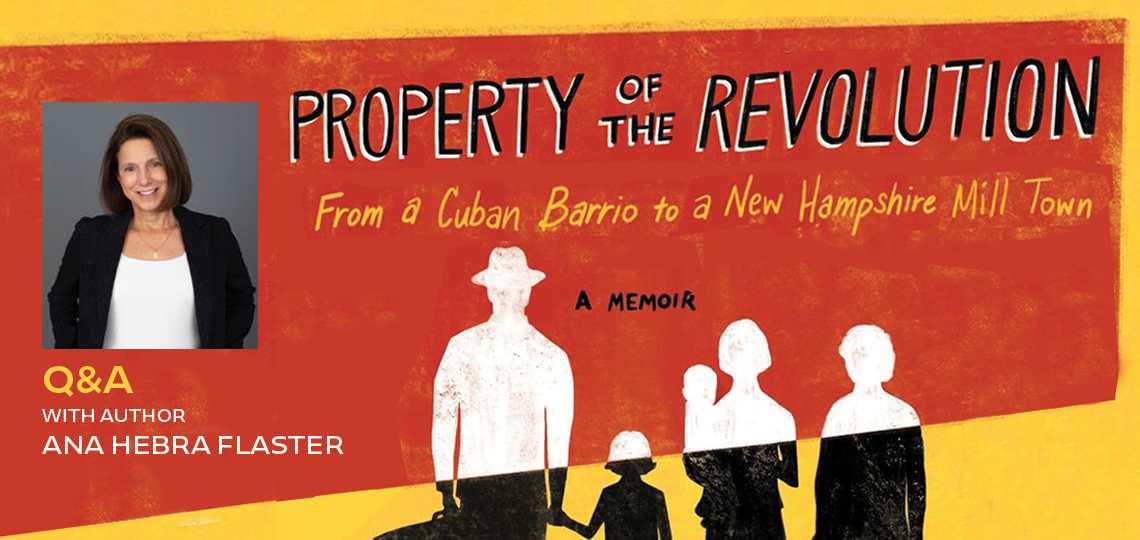

An Interview with Ana Hebra Flaster, Author of Property of the Revolution: From a Cuban Barrio to a New Hampshire Mill Town

Every American immigrant story is both unique and similar to the tens of millions of emigrations that have taken place over the centuries from many dozens of far-flung nations. But one country stands out for its entrancing history and troubled relationship with the United States: Cuba. Interestingly, that fractious relationship is largely connected to the mindset and actions of Cuban Americans, many of whom want to see an end to Cuba’s Marxist-Leninist regime and democracy restored to their homeland. These expatriates still view the revolution’s broken promises to restore Cuba’s 1940 democratic constitution and hold free elections as the ultimate betrayal. Many have family and friends on the island, send them moral and material support, and closely follow their ongoing struggle for a better life, freedom, and human rights.

In today’s interview with Foreword‘s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland, Ana Hebra Flaster provides remarkable insight into the complicated status of Cuban Americans—her mother joined the rebel forces during the Revolution, after all—and yet, her story most resonates on themes of familial love and America’s endless capacity to embrace newcomers.

Property of the Revolution: From a Cuban Barrio to a New Hampshire Mill Town is Hebra Flaster’s first book. She has written about Cuba and the Cuban American experience for national print and online media, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and The Boston Globe. Her commentaries and storytelling have aired on national broadcasts of NPR’s All Things Considered and PBS’s Stories from the Stage.

After a careful and delightful read of her Property of the Revolution, Matt connected with Ana for the following conversation.

Property of the Revolution follows the arc of your extended family from Juanelo, Cuba, during the last days of the Batista dictatorship to 2005, to nearly forty years after your emigration to the states. Amazingly, during the Cuban Revolution, your mother (Mami) actively supported the rebels—including Fidel Castro’s group—seeking to overthrow Batista. For our readers without a solid understanding of Cuban history, can you tell us a bit about the political situation in the early ’50s and why the Cuban people were so primed for the Revolution.

Most people don’t understand that most Cubans were not expecting a communist revolution when the rebels rolled into Havana in January 1959. My memoir brings that to light and focuses on the plight of our working-class family and barrio.

Like most Cubans, my family wanted an end to Batista’s dictatorship and its corruption, and the restoration of the 1940 constitution, a model of liberal democratic principles that had seen the country through peaceful transfers of power during that decade. All three anti-Batista rebel fronts, including Fidel Castro’s, promised just that: ousting Batista and restoring democracy.

Cuba had a strong economy in the 1950s and ranked highly in our hemisphere in key economic development categories like literacy, hospital beds per capita, miles of paved road, rail system, etc. There was a long history of diverse political parties and views, including an active Communist Party even under Batista, and a robust independent media scene, though this was partly censored by the Batista regime. The peso traded at a 1-1 ratio with the dollar and the country had never run a trade deficit; each year it exported more than it imported. There were disparities between urban and rural areas, as in most countries at the time. But those were not the main concerns. The main concern was corruption.

University students, in particular, actively opposed Batista. Militant students sometimes used weapons, including bombs, in their fight against his regime. Batista forces brutally repressed opponents. Many were beaten, tortured, or killed during his six-year rule. And many innocent Cubans were killed in the crossfire.

All of that, as you describe, primed average Cubans for political change. They weren’t necessarily looking for a revolution, but they saw it as the vehicle for the political change they’d been seeking. My mother, a 17-year-old working-class high school student, tried to join the rebels in the mountains, but ended up a member of a clandestine anti-Batista cell in Havana. She collected money and medicine to support the rebels. She was almost arrested once, but a quick-thinking neighbor used his status as a police officer and saved her.

Having risked her life to help restore democracy to Cuba, my mother felt deeply betrayed when the rebels came to power and, instead of restoring democracy, created another military dictatorship, a communist one that turned out to be far more repressive than Batista’s. Many Cubans felt the same way. Life turned upside down, and, like tens of thousands and eventually millions of Cubans, my parents realized they’d have to find a way out of the country.

That had become an ordeal after the revolution. For the first time in Cuban history, the government was demanding that citizens obtain its permission before leaving the country. To apply for *permisos *to leave, people had to declare themselves enemies of the revolution. They had to resign from their jobs—because jobs were only for revolutionaries. They would have to turn over all possessions, homes, bank accounts, cars, etc., to the revolution when they left. Nothing of value, including diplomas, could be taken out of the country.

There was no guarantee you’d receive your permiso. No one knew when or if it would arrive. So people waited anxiously for years. Some never left. We waited for three years before ours arrived. As working-class Cubans, my parents didn’t have much material wealth. But four generations of both families lived in the same barrio, and they had life-long friends there as well. Leaving them and knowing they’d probably never see them again or be able to return was the price they were forced to pay. For freedom.

Your mother was very close with an uncle, Tio Manolo, who was more skeptical of the rebels’ ability to put together a government even as he despised Batista. Was there ever a realistic chance that a less radical government might have come together rather than the Marxist one under Castro—he being known for long ranting anti-American speeches with arms flailing in the manner of Mussolini and Hitler? What was the final straw for your mother and family to finally turn on Castro in 1964?

I think most Cubans thought it entirely plausible that the rebels would restore democracy. The rebel groups had all promised that. Fidel Castro firmly and repeatedly denied Marxist affiliations until after the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961. He described the revolution as being as “green as the palm tree.” With the Cold War well underway, most Cubans were staunchly anti-communist, and firmly aligned with the US, as was Batista. Many came and went between the two countries or had family in the US. But a contingent among the rebels was staunchly Marxist Leninist, Fidel’s brother, Raul, among them.

After Fidel declared the revolution would be a communist one, some rebels broke rank and began a counter revolution. Castro’s forces responded brutally, torturing and executing many opponents who were caught. Along with thousands of Batista’s guards and supporters, many innocent Cubans were swept up in what Che Guevara later described as necessary “revolutionary hygiene.” They were arrested, denied due process, sentenced to many years’ imprisonment, or executed.

About Fidel’s dramatic style. You’re absolutely right. As a college student attempting to win elections, he studied recordings of Mussolini and Hitler and adopted their style.

With flashback-flashforward chapters, you proceed to tell the remarkable story about how your grandmother, aunts, uncles, and parents went through the arduous, three year permitting process of leaving Cuba for the US, finally arriving in New Hampshire in December of 1967 when you were six. In those in-between years living in Cuba after your family filed for an exit visa, you all were looked down upon as gusanos by many of your neighbors. What does that word mean and why was it such a difficult time?

Gusano, worm, was what the new revolutionary government called people like us who wanted to leave the country or didn’t actively support the revolution. In the book, I show how life after the revolution centered around politics and proving your loyalty to the Communist Party, the revolution, and, above all, Fidel. Gusanos were the antithesis of the revolutionary ideal. They could be harassed, detained, imprisoned, beaten—their homes vandalized. There’s a scene of that in the book.

You could be denounced publicly as a gusano even if you weren’t trying to leave the country. All it took was for someone to accuse you of lacking revolutionary fervor, being religious, missing mandatory meetings at work, failing to volunteer, dabbling in bourgeois pursuits like listening to rock and roll, wearing jeans, etc.

Gusanos who were waiting for their permisos could still use their ration books, which had never existed before the revolution, to buy food. But without jobs they had to rely on family and friends for donations, or risk bartering or selling things on the black market. Profiting from a transaction was forbidden. There’s a story in the book about what happened to one of my mother’s students when he and his father were caught.

From the moment people applied to leave the country, they were outed and completely vulnerable to anything and anyone.

Why snowy New Hampshire instead of sunny South Florida as a final destination for your family? What cultural differences between Cubans and Americans began to surface as you settled into your life in the northeastern US?

A family of carpenters from our barrio had settled in Nashua, New Hampshire, when a Baptist church sponsored them and brought them north. They found out, somehow, through the Cuban grapevine that we’d made it out also and were living in New York. They came to visit and told my parents, who weren’t happy with city living for us kids, that Nashua was great. There were plenty of factory jobs, perfect for non-English speakers, great public schools, lots of room for kids to play, and the people were mostly very welcoming. The snow … could be a problem, though. But they were getting better at dealing with it and would help us.

My aunt didn’t want to leave the city, but splitting apart was unthinkable. In one weekend, my father found a house to rent and jobs at a factory for all the adults. The landlord at the old farmhouse he found was the foreman at a factory. He offered to rent the house to Papi without a deposit and told him to pay him the first month’s rent after the new factory workers in the family got their first paychecks.

“Cultural differences” doesn’t begin to describe what we collided with. The climate alone, with blizzards and below zero temperatures, terrified the adults. My grandmother thought we’d all die of pneumonia. She bundled us up every morning so tightly that we could barely walk. The new friends from the factory showed us how sand and salt and chapstick could save your life in winter. They taught us about central heating, and explained that my parents didn’t have to keep shoveling the yard each time it snowed. American kids played on top of the white stuff just fine.

No one understood sleepovers. Why do the Americans send their children to sleep at strangers’ homes when they have their own beds at home? We were in a Spanish desert. No Spanish TV, radio, or print media. If the adults heard someone speaking Spanish at the grocery store or the bank, they’d run in their direction and hope they’d become a friend. Usually, the lone Latino/a was equally eager to find us.

When I got to high school and wanted to date, my grandmother was supposed to be in the backseat. I rebelled against that and other signs of what I called Cubanosity. I wanted nothing more than to be an independent American girl like my friends. The problem was that independence wasn’t valued much in Cuban culture. Being called muy independiente, very independent, was the common criticism when someone acted in their own self-interest too often, broke out on their own, separated from the clan.

Much of the struggle with identity—and with our viejos, our elders—stemmed from the value clashes between cultures. Were we Cuban? Were we a mix? Could we become just plain-old Americans and shed the Cuban stuff?

Your father played professional baseball in Cuba, Mexico, and the US, and raised you to play, as well. But all that changed the day you became a señorita in the mid seventies and your parents forbid you from playing. This was just one such “load of Cubanness,” or “Cuban weirdness,” as you say, that landed on you as a young spirited American girl being raised in a conservative migrant family. What was your relationship with your mother like at this time and through your teen years?

Mami was the youngest of the viejos. She picked up English quickly and spoke it better than the other viejos. And her job as a manager at a large CVS kept her in touch with pop culture and the young people she employed. All of that helped her see things my way many times. She helped me persuade my father, for example, that it was okay for me to go off to Smith College, even though I wasn’t married. She covered for all of us, but not always. She was Cuban inside, even if she appeared more American than the other viejos.

Besides your mother, you had other strong women in your corner. In a passage about your maternal grandmother, Abuela, and mother’s sister, Tía, you write: “These two hyper-traditional women always left a few open spaces where their children’s dreams could live. I never knew where those holes were, but I knew that they existed and that the only way to find them was to tell Abuela and Tía what my dreams were. Once they understood, they banded together in their common cause: us.” Which begs a question about the Cuban men in your life at that time? What was it like for these men when they settled in the US? How does your Cuban background shape your views on masculinity?

My father was a tough barrio jock who thought it was honorable to fight with anyone who insulted him and, especially, his family. In Cuba, that fist-first reaction was accepted, part of macho culture. He struggled all his life to understand that Americans looked down on that behavior. He was eighty-nine years old when someone accused him of cutting in a line at a grocery and he came inches from getting into a fistfight with a guy in his prime.

My uncle, my second father, was more even keeled. He rarely lost his temper and wasn’t the typical macho Cubano. I think I looked for more of the American norm in men. I wasn’t impressed with tough guys. Maybe it had to do with my longing for much of my teens to be as American as possible.

You were traumatized by a house fire as a child, developed terrible sleep problems, and later, experienced long periods of severe depression. Do you believe these mental health challenges relate to the trauma of leaving Cuba under such difficult circumstances? What was the process of healing like for you?

Absolutely. There’s definitely a family pattern with depression but the childhood insomnia, fear of fire, the voices, and later a depression that hit as my daughter turned the age I’d been when we left Cuba all pointed at that early trauma as a factor, if not the cause.

In 1999, you and your mother traveled back to Cuba. Please talk about what that trip meant to you both?

Extremely emotional for both of us. Like most Cubans, we stayed with our family, not in a hotel. We saw how hard life was, how proud they were of the many work-arounds they’d come up with, from concoctions that served as shampoo when none was available to making car parts of out cardboard. And they worked.

The worst part was knowing there was hunger. Probably not starving level hunger but, as my uncle used to say, there are many kinds of hunger. One is when you want to eat something that you see tourists eating but you will never be able to find in a store let alone afford.

I was surprised by how at home I felt, like everyone was related to me. I could see myself in their faces, something I realized had never been the case in the States. Even better was the relationship I was able to forge with my cousin, who was born after we left in 1967. We stay in touch. I’ve brought my family to Cuba and she, when it was possible, brought her family here. So now our children have at least met and have a connection.

Can you talk about your research, interviews, and other preparation required to write this incredibly detailed and history-laden book?

I’ve been reading about Cuba since high school, studied its economy in college, and have followed it closely for my writing. Recent books like Anthony DePalma’s The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times, Aran Shetterly’s The Americano, and older ones like Peter Wyden’s The Bay of Pigs, and Georgie Geier’s Guerrilla Prince have given me a broader view of the story than the first-person accounts I grew up hearing. Cuba 1952-1959, by M. Márques-Sterling, is meticulously researched and full of useful citations about the period just before Castro’s takeover. For a history of the Mariel Boatlift, Mirta Ojito’s Finding Mañana was invaluable. FM and the 2003 National Book Award winner, Waiting for Snow in Havana, by Yale professor Carlos Eire, were inspirational.

Primary sources are still the keys to my understanding of Cuba and the Cuban American experience. Nothing beats a first-hand account that is confirmed and strengthened by other eyewitnesses. I experienced that growing up, and the opportunities for it have only grown as my network of Cubans in and outside of Cuba expanded over the decades. I have many hours of interviews with my own viejos about their experiences. I treasure them.

Here it is 2025. What does your extended Cuban-American family look like now, nearly sixty years after leaving Cuba? Is there some type of bond that remains to the old barrio in Juanelo, Cuba?

We are about thirty people now, and the family is truly a blend of cultures. Beautiful partners have entered the family and given us Asian, Black, Irish, and French culture and history to pair with our own. Most of us are in the southern New Hampshire area, but some of the younger generations have moved a plane ride away—too far for me, I’m afraid. I’m greedy about my family, and as the matriarch I want to keep everyone close by so I can pass down our traditions to the new generation, so that cousins are more like brothers. That’s how I grew up and would want the same for any child.

How has your family responded to your book?

They are extremely proud of the book. They’re also probably glad I won’t be moaning about it anymore. They’ve loved the stories, the way the viejos’ embody humor and strength. My oldest cousin has corrected a few minor points, showing me, once again, that he outranks me.

I didn’t realize how hard it would be for my cousins and brother to read the book. It has forced them to confront a time of profound confusion, change, sadness mixed with excitement, and the fact that there was, indeed, trauma. I’d had time to come to terms with that very quiet part of our origin story, but they hadn’t. It’s been tough for them, especially, I think, as Latinos who don’t always like to dwell on such complex emotions that often require some crying before the dust settles.

Matt Sutherland