Family separation, detention, and birthright citizenship

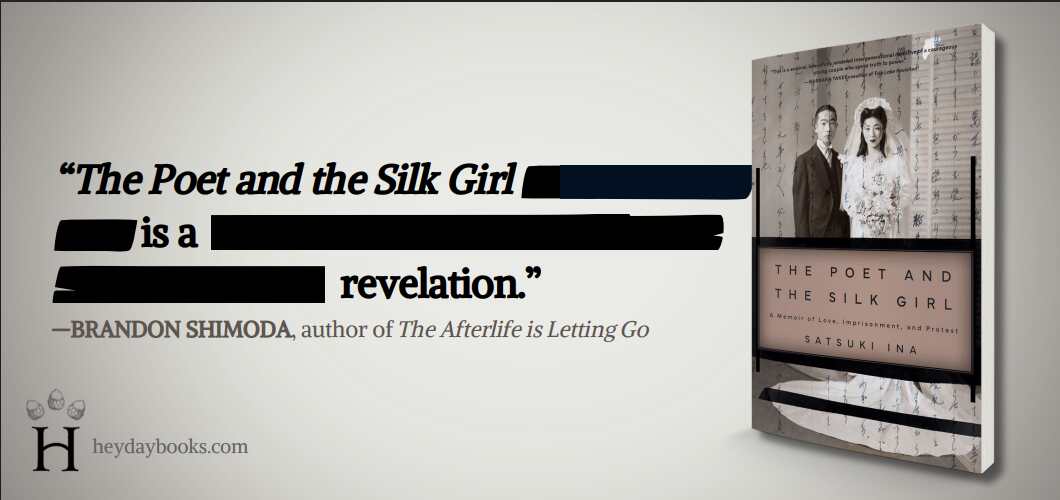

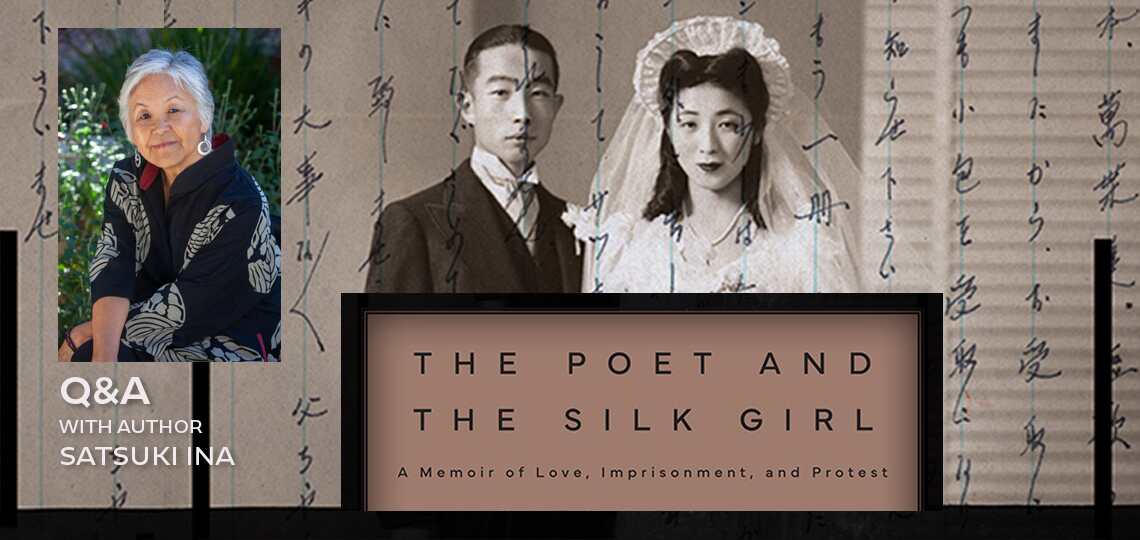

How One Survivor of WWII-era US Concentration Camps is Speaking Out Through History: An Interview with Satsuki Ina, Author of The Poet and the Silk Girl: A Memoir of Love, Imprisonment, and Protest

Early in Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl discusses the experience needed to make accurate observations about life in a concentration camp and concludes that outsiders are “too far removed to make any statements of real value. Only the man inside knows.”

The extraordinary psychological insight in Man’s Search would certainly prove his point, but Frankl is matter-of-fact about his place in history: “We are indebted to the Second World War for enriching our knowledge of the ‘psychopathology of the masses, … for the war gave us the war of nerves and it gave us the concentration camp.’”

Like Frankl, today’s guest, Satsuki Ina, is a psychotherapist as well as an insider at WWII concentration camps, albeit ones in Northern California and Texas. In fact, Satsuki was born in California’s Tule Lake concentration camp, one of the six her parents were imprisoned in shortly after being married in 1942. In The Poet and the Silk Girl, Satsuki tells of their tragic love story and the racist mistreatment they suffered at the hands of the US government. And like Frankl, Satsuki’s psychological insight captures the generational wounds suffered by her family as they fought to restore their rights and dignity over decades.

As the 80th anniversary of the closing of Tule Lake concentration camp approaches early in 2026, we assigned editor Danielle Ballantyne to connect with Satsuki for an interview. Satsuki was gracious enough to accept.

As you were working through the poetry, diaries, and letters your parents wrote throughout your family’s time at Japanese American concentration camps during WWII, at what point did the idea for this book come to you? Was there a particular passage or event within these materials that inspired you to center a book around them?

As the poetry, diaries, and letters were being translated from Japanese to English, page by page I began to realize that my parents’ trauma-laden silence, reinforced by the government narrative that labeled them as “disloyal” to America, had led to a generally accepted false narrative about their decision to renounce their American citizenship. My parents never had a crisis of loyalty. What they suffered was a crisis of faith—in the country of their birth.

Unjustly imprisoned, they feared for the life of their children. So, when my mother wrote in her diary, “I wonder if today is the day they’re going to line us up and shoot us,” I was overwhelmed with grief and anger. It was then I realized their story needed to be heard.

You mention within the book that you had initially sought to keep your own voice out of it, focusing only on the “primary resources,” as you call them: letters, diary entries, photographs, etc. What was it like diving back into these materials after being encouraged by your editors to include yourself in the story? How did that change your approach?

I struggled. My own trauma as a survivor had somehow kept me from believing that my voice was significant, that proof of my parents’ innocence could only be believable if it was documented by real documents written at the time it was all happening. Trauma neurosis. I was still surrendering myself to the authority of the prison keeper.

I’m now so grateful to my editor for pressing me. It took another five years to go back and unwind my own healing journey. I talked to friends and family. With time, the more I got in touch with my own righteous indignation, or better said, how deeply pissed off I had been, I slowly felt the burden of silence lifting from my shoulders. I let myself feel my parents’ pain, a kind of empathy I had been afraid to embrace. I could finally tell their story, and my story, with passion and purpose.

How do you feel your expertise as a psychotherapist specializing in community trauma impacted your approach to the memoir? Was balancing the professional assessment and the personal connection ever difficult?

I think my career as a psychotherapist specializing in community trauma was always an unexpected pathway to my own healing. In my work supporting communities experiencing refugee acculturation trauma, generational clergy sexual abuse, Asian hate, mass removal, detention, and deportation, etc., I often wondered what it would have been like if my parents, my community, had been able to gather, find strength in their own values, culture, and self worth. Intergenerational transmission of trauma might have been staunched.

Balancing the professional assessment and the personal connection wasn’t difficult. Seeing my own personal connection through the lens of psychology has been for me, the bane of being a therapist. I haven’t been able to escape the obsession I have of examining every relationship and situation from a psychological perspective. Once I was given “permission,” my writing seemed to flow.

To say the dark chapter of the Japanese American concentration camps is insufficiently taught and discussed within the United States today would be an understatement. I, for one, had never heard of Wayne Collins, the attorney who took on the government in a class-action lawsuit on behalf of internees who had been forced to renounce their US citizenship while incarcerated. Did you come across anything in your research on the topic that was surprising to you?

What was surprising to me as I did the research on the renunciation process was the complicity with which US authorities had moved to be rid of dissidents. The Renunciation Act was pushed through the legislature within weeks. Wrapped in a bow with language of the benevolent oppressor, giving the appearance that this was something Japanese Americans were wanting, people who had been unjustly incarcerated were now given “permission” to give up their birthright citizenship. Framed as an action that proved their “disloyalty” to the US, renunciants like my parents were stigmatized and shamed even by their own Japanese American community for decades after the war. Sifting through this government narrative as opposed to the context and story of survivors, including my parents, was not only a revelation, but a redemption!

You mention visiting other, modern-day detention centers in the book, including a family detention center in Dilley, Texas, where you and other camp survivors, as well as local allies, protested the incarceration of refugee families fleeing Central America. On the transformative revelation of the protest, you state, “Every child in detention today is my brother, my community. I am every child in detention.” Your book, naturally, stops short of these recent events, but what is it like to see the Trump Administration’s “immigration crackdown” fast-tracking recreations of your own traumatic history for other families and children?

Some of us survivors of the WWII incarceration have lived with symptoms of post traumatic stress. Witnessing past and current “immigration crackdown” has had profound impact on us. As for me, heightened anxiety and dread have sometimes been overwhelming. But moving to action, mobilizing others in the community to press their government representatives, respond to meaningful petitions, and to show up in protest, has helped me and others to “fight” back, rather than “flee” or “freeze” when our own trauma response is triggered.

Our organization, Tsuru for Solidarity, has had a dramatic increase in membership as Japanese Americans join us in collective effort to have a voice and presence to fight back in ways we didn’t/couldn’t when we were the targets of racist oppression. We’re now empowered to use our moral authority to speak out against authoritarianism.

That protest action in Dilley was the beginning of a national Japanese American social justice organization, Tsuru for Solidarity. Can you talk to us a little about the organization, what you do, and how people can get involved, if they wish.

In 2018 while participating in a pilgrimage to the historic site of the Tule Lake Segregation Center where I was born, with 400 other survivors and descendants, we received news that Trump policies to separate children from their families were being immediately implemented. Waves of anger spread through the gathering as we all identified with our own family separation trauma 80+ years earlier. Leaders quickly gathered us all together in front of the “jail within the jail” where my father had been held and beaten in 1945. We began to chant, “kodomo no tame ni” (for the sake of the children), they’re our children, set them free! Mike Ishii, my activist friend said we need to carry our voices of protest to the world. We needed to show up for those who were being targeted today.

We are now a non-violent social justice organization made up of hundreds of volunteers working to organize our communities in multiple states to speak up and show up to protest against the repetition of our history. Survivors in their 80s and 90s, with their hearing aids, walkers, wheelchairs, show up at detention sites along with descendants and allies to speak out against current inhumane policies criminalizing immigrants. People can learn more about what we do at: www.tsuruforsolidarity.org.

You’ve already created two documentary films, published poetry, and written this memoir—on top of your work with Tsuru for Solidarity and your career as a psychotherapist. Are there any more projects in the works for you that you can share with us?

Yes! The paperback version of The Poet and the Silk Girl: A Memoir of Love, Imprisonment, and Protest, along with the audiobook of the same title, will be available September 9th.

I am currently working on two books. One is a compilation of my father, Itaru Ina’s, prison haiku, currently titled, Snow Country Prison. Translations from Japanese to English have been completed. I am now editing and writing the contextual narrative. My second project is a children’s book, currently titled, My Name is NOT Sandy! It’s about a third grader whose teacher tells her parents, “If you want your child to be a real American, she should have an American name.” As you might have expected, she’s a tough cookie. She resists and protests, and eventually reclaims her birth name—something I wish I had done when I was a kid!

Danielle Ballantyne