Editor-in-Chief and Executive Editor Interview Michael Twitty, Author of Recipes from the American South

Editor-in-Chief and Executive Editor Interview Michael Twitty, Author of Recipes from the American South

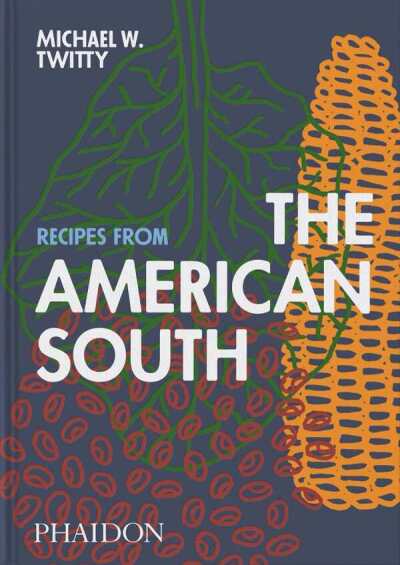

Without a doubt, Southern food is America’s favorite cuisine—which means that we’re always on the lookout for stellar new projects that enrich our understanding of the food, traditions, history, and agriculture of the American southeast. After devouring books like Koshersoul, Rice, and now Recipes from the American South, southern author and historian Michael Twitty has been our go-to guy.

Rachel Jagareski’s starred review of Recipes in Foreword‘s September/October issue prompted Michelle and Matt to team up on a batch of thoughtful questions to pitch at Michael for this week’s conversation.

If you’re looking for more books that exemplify great regional writing, check out these four INDIES-award-winning titles.

Michelle: What does it mean to you to be a memory keeper for Southern cuisine?

It’s lonely. I know I’m not the only one but … I feel like my niche, the food world of the enslaved and their descendants is extremely endangered. I also feel very connected and grounded and supported. It’s a great builder of my intuition and gives me comfort with anxiety.

Michelle: We love how you infuse history into Southern kitchen staples: corn evokes Native American populations; black-eyed peas speak to West African influences and the slave trade. There’s an intentionality to this that makes single dishes bigger than the single meals they are part of. What might people gain were they to practice cooking and eating with such thoughtful awareness?

I think it engenders respect for our food’s origin story and appreciating the power of food narratives to understand ourselves. The way we add to or change things and keep traditions going while being intentionally dynamic is how we get to the best cooking. Context, imagination, sourcing, and joy are key ingredients.

Michelle: We’re also fans of Koshersoul, wherein you discuss what it’s like to be a Black and queer American Jew. If you had to represent your multicultural background in a meal, drawing on the dishes in Recipes from the American South, what would you be serving?

Oh, Sephardic Pink Rice and Gullah Geechee red rice all on the same table, because rice … lol…

Virginia fried apples, okra soup, Maryland fried chicken, matzoh balls and collards, and cathead biscuits and Coca Cola cake.

Matt: Of the many compliments we can pay Southern cooking, perhaps the most flattering is that it may be the top comfort food of all. Why do you think it appeals to people on such a deep, soulful level?

Southern food at its best and most just is a vehicle. It’s a powerful way to send care, hospitality, welcoming, and love. It says a lot with taste, smell, feel without saying a word except for the eaters “ahhh.”

Matt: Towards the end of the book you write, “Southern food is emblematic of life’s path and the journey through Southern identity and knowledge transfer.” Can you unpack that statement a bit for us?

I learned what I know in bite-sized kid moments that became chunks of my life. I can remember how my mother and grandmother and father and others looked at me, the interactions as I snapped green beans, learned to barbecue. It’s nostalgic but it’s kinda sad and wistful too. You look back and you feel amazed that somewhere between your brains and your hands you learned something older and bigger than yourself that you now get to add to.

Matt: Southern food doesn’t shy away from lard, ham hocks, sweet barbecue sauces, dumplings, hoecakes, hush puppies, deep fried pork chops, hog chitlins, and a seemingly endless number of decadent desserts. All of which, of course, gives it a bad rep in certain circles for being somewhat unhealthy. Would you care to comment on that reputation?

In contemporary American culture, celebration food is often confused with everyday food. Many of the foods you mentioned are Sunday dinner or holiday dishes, cakes served at church suppers, potlucks, or life cycle events. They were never meant to be associated with day to day life. Now that they are it’s our job to be responsible in our food associations and our consumption.

Matt: Is it fair to say that Southern cuisine reached its peak during the Antebellum years on plantations with African slaves? How influential were Black African women cooks and gardeners in reaching those heights? How much of a role did the Native American population play at the time? And, what historical materials (old cookbooks, diaries, ledgers, daily logs) still exist to help answer these questions?

Perhaps, but to be clear it’s because it was pre-industrial hyper local food made by people who had no choice but to make it their best. That’s the formula. Indigenous people and enslaved Africans had a profoundly intimate history in the South and that made our food so much richer. The family tree of Southern food is impossible without its oral histories, songs, proverbs, written records and narratives without which we would have a sorely broken mosaic.

Michelle Anne Schingler