Are they gaslighting you, or do they just disagree?

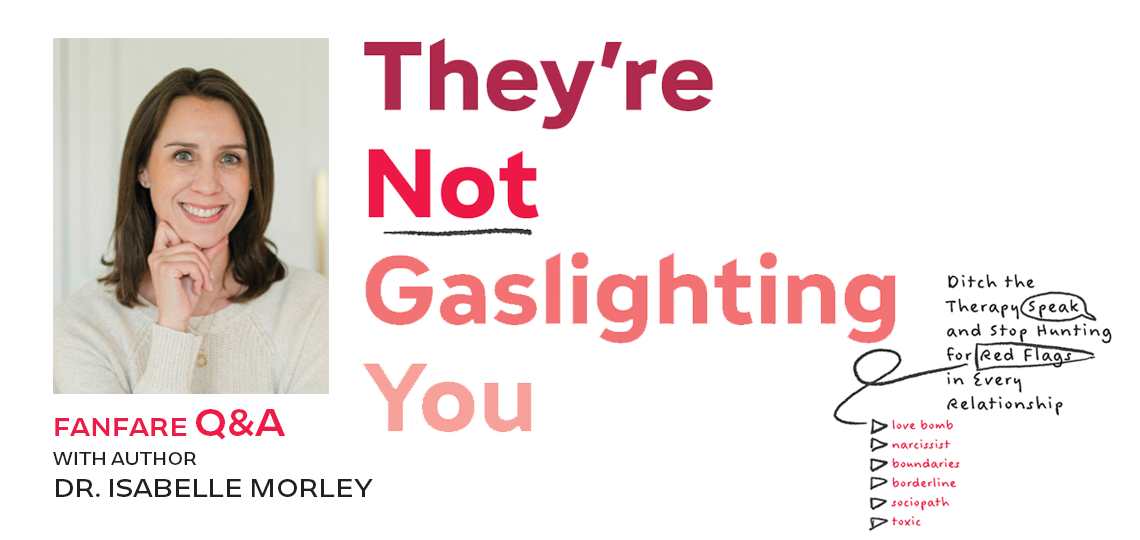

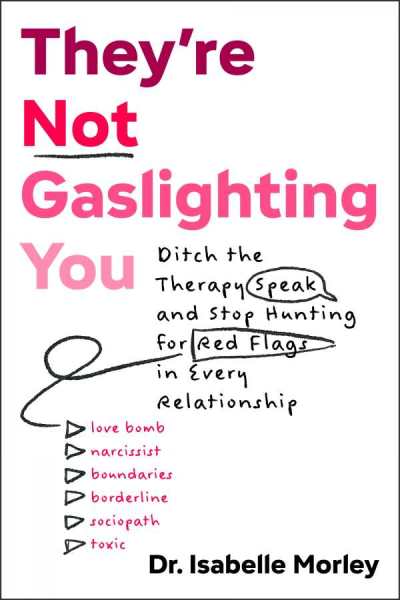

Reviewer Katy Keffer Interviews Isabelle Morley, Author of They’re Not Gaslighting You: Ditch the Therapy Speak and Stop Hunting for Red Flags in Every Relationship

After a years-long perfect storm of Covid isolation, social media distraction, texting becoming the go-to communication tool, and therapy language—you’re a narcissist / no, you’re bipolar—leaking into every disagreement—do we dare ask after the state of romantic relationships in this country? Poor Cupid doesn’t stand a chance.

It’s not that there was a golden era in the past. Intimate relationships have always been challenging, but the current environment is unprecedented in its insolvability. Clinical psychologist and couples therapist Dr. Isabelle Morley sums it up this way: “We live in a very difficult world, with many realities that do notable harm to our mental health. The pandemic was such a distinct blow to our mental health and our relationships, and then social media is a lesser but persistent erosion to these things as well. And we can’t control it!”

Feeling a personal obligation to help right this imbalance, Isabelle decided to be part of the solution. “As a true romantic who loves love, I wanted to help others (and myself) better understand what makes romantic relationships successful. … I channeled my anxiety into something productive: making a career out of ensuring I knew all there was to know about successful couples! So here I am, ten years in, doing that every single day and absolutely loving it.”

We discovered this intimacy innovator when her new book, They’re Not Gaslighting You, earned a glowing review from Katy Keffer in the pages of Foreword. The opportunity to learn more about her love-saving strategies was too inviting to pass up.

Enjoy the interview.

You were forthcoming in your book with personal anecdotes, but what originally inspired you to pursue a career in clinical psychology? And how did you find yourself wanting to focus on couples’ relationships?

I’ll cut to the chase: I’m a middle child. I have three siblings and I was always interested in (and overly involved in) family dynamics. I cared a lot about keeping the peace, which made me an excellent human observer and also sparked a real interest in understanding people and relationships in greater depth. I’ve always wanted to help people find harmony. For example, I was a peer mediator in high school and in college at Tufts (shoutout to my fellow Jumbos!) I worked at the student-run helpline. There is nothing more meaningful than helping people find their way from conflict to harmony.

Funnily enough, I didn’t major in psychology. I majored in Peace and Justice Studies with a focus on interpersonal conflict resolution, so clearly I had a thing about helping people not fight. Once again, classic middle child. My focus became romantic relationships instead of, say, family ones, after surviving college hookup culture and realizing how hard romance has gotten. There are no rules now. No playbooks. People aren’t learning how to date—how to communicate, slowly increase emotional intimacy, manage conflict as it arises—and that’s making relationships very hard to sustain.

As a true romantic who loves love, I wanted to help others (and myself) better understand what makes romantic relationships successful. I personally didn’t want to miss out on building the necessary interpersonal skills for having a partner, so I channeled my anxiety into something productive: making a career out of ensuring I knew all there was to know about successful couples! So here I am, ten years in, doing that every single day and absolutely loving it.

This was an enlightening and fascinating read. The title of your book alone drew me in as I wanted to better understand the term gaslighting. You noted the concept originated as early as the 1944 movie Gaslight, and the term took off in the 2010s, though it is now being misused as “weaponized therapy speak” in labeling relationship behavior. Can you expand further on why you think people are weaponizing this and other therapy terminology in their relationships?

That is a great question that I’ve asked myself many, many times over the years. We live in a culture of optimization. We all want to have a clear view of our lives and how we can make them better. The best they can be, in fact. And our relationships are a big part of this. When people feel frustrated or upset by their partners, they want to know why. Why did that person hurt their feelings, or why didn’t they consider the impact of their actions? And the most likely answer—because they’re human and imperfect—isn’t satisfying, in part because we don’t want to face the painful truth that this answer means we’ll get hurt again. Our parents will make passive-aggressive comments about our jobs, our siblings will exclude us, and our partners will sometimes ignore our repeated requests to put the dishes in the dishwasher. We don’t want this to be the case. We want lasting change, but to get that, we feel we need to identify the behavior as pathological and force the other person to “get help” and stop frustrating us.

There’s also a belief that accepting human imperfection as the answer for others’ shortcomings lets them off the hook for accountability (people are big on accountability these days). We want real answers, clinical answers, that can explain our level of distress and give us a way to fix it (which usually means fixing the other person). Therapy terminology does all of that; it gives us an answer, it tells us how the other person needs to change so they don’t hurt us again, and it conveniently absolves us from feeling responsible for any part of the difficult interaction.

You write about the social media and internet influence on better understanding clinical diagnoses, noting the positives in raising awareness, but also the downsides since search algorithms can create confirmation bias. Can you address more about the role of the internet and social media on misuse of terminology? Could this “weaponization” have perhaps originated there?

I think social media is the main source of this problem. Its content requirements force creators, including experts, to distill really complex topics or disorders into seconds-long reels. There’s no way people can get a full or accurate picture of something like sociopathy when they’re learning about it from Instagram.

Also, the intimate nature of social media reduces clinical accuracy. Personal experiences become universal truths. But just because an influencer diagnosed with bipolar disorder reports a certain symptom, it doesn’t mean that anyone who sees their reel and has that symptom also has bipolar disorder. But humans are hardwired to relate to others, so it’s easy for us to make this connection and arrive at a false conclusion.

I also have to lay some blame on therapists. In our attempts to educate and help our clients, we’ve gone a step too far in pathologizing people in our clients’ lives. We’re too quick to point out possible narcissistic traits or evidence of boundary violations. We’ve introduced these terms into the lexicon without enough caveats about when and how to use them. Clients haven’t been taught the importance of being judicious with these words, which is something we therapists learned in grad school in our psych assessment courses. Therapists opened the door for everyone to use these terms without the right caution and framework for doing so.

In the book, I gravitated toward your comments that we are all “messy human beings,” who can miss out on self-reflection and growth if we incorrectly associate someone with a clinical term. You wrote, “the truth is that we don’t need to label someone to understand them or work on improving our relationship with them.” Given that social interactions today lean more often into the digital space, how do you think this has affected people’s ability to communicate and have heartfelt and open conversations with their partners, significant others, friends, and family to help improve relationships?

These conversations are less common in person. More often, people are texting or emailing, or even sending posts and reels to their loved ones to explain their feelings. People are working hard to identify and label problems rather than diving into the real work of addressing them. I’ve seen couples argue via text about who was right or wrong in a situation (a common but very unhelpful argument) instead of sharing the important thing: how they felt because of the situation. People go cerebral and logical instead of emotional, and this gets in the way of true connection. Humans connect through our shared feelings, not our cognitive battles.

I want to acknowledge that what I’m advocating for is hard. Being vulnerable (in person, no less!) with someone who hurt you feels very scary. It’s far easier to send a post that explains covert narcissism, hoping the other person takes the hint and shapes up. Admitting your pain to the person who caused it does put you at risk for further hurt, but it’s also the only path to repair and reconnection.

Also, people are hard to talk to these days. There’s such a focus on communicating in the “right” way that people start arguing about how they’re talking instead of just talking. Mistakes are caught and amplified. “You didn’t validate my feelings before sharing your own!” gets into a fight about when and how to validate, and many other tangential arguments can stem from there. And listen, there are more effective ways to communicate, but people are too focused on them. I know all the “right” ways to talk through conflict, and sometimes (perhaps many times), I just don’t use them. We have to give some grace as people muddle their way through conversations or conflicts with us.

I also loved your use of relationship vignettes throughout the book as a teaching tool to depict correct and incorrect behaviors in someone. Are there other tools you may refer our readers to learn more? Any specific recommendations you would prioritize from your list of resources or bibliography?

I have to first give a shoutout to my amazing colleague and dearest friend, Dr. Bailey Hanek. It was her brilliant idea to include vignettes. Hopefully they help readers see that identifying a label or disorder is hard. I tried to make the correct depictions overly obvious and the incorrect ones more nuanced, so people can see how much critical diagnostic information they’re missing, such as what the other person is feeling, what’s driving their actions, and how they feel after.

But yes, further resources! I include a chapter on recommended books so people can dive deeper into what healthy relationships are or specific terms/disorders they’re curious about. If readers are wondering about the health (or possible abuse) of their relationship, I’d recommend reading Is It Supposed To Be This Hard? by Mary Pat Haffey. She explains how to tell the difference between normal relationship hardships and emotional abuse. I’ve recommended this book countless times. I’d follow it up with Too Good to Leave, Too Bad to Stay by Mira Kirshenbaum. What I love about this book is that it doesn’t focus on whether your partner is diagnosed with something, and it asks very practical and important questions to help you decide if you should stay with the person.

If you’re in a pretty good relationship but think it could be a lot better, my top book recommendation is Secure Love by Julie Mennano. I ask every couple I work with to read this book, it’s that good. She explains how people can get caught in a negative cycle, and while their behavior isn’t helpful, it’s not necessarily pathological. She humanizes the struggle of being in a close relationship and helps people return to a secure attachment. Absolute gold.

You ended your book with a brief chapter devoted to the terms “toxic,” “triggered,” and “trauma bonding,” noting you wanted to cover these in some detail but lacked the space for detailed examples. Would you like to share more or offer some other terminology that may have increased in misuse lately?

I’m so glad you asked this! I tortured myself over this chapter when trying to pick these add-ons. I wanted to add so many other words, but I just didn’t have time to cover everything. I think “trauma” could have had its own chapter, along with its associated words like “triggered” and “trauma bonding.” People really misunderstand trauma these days.

People often use “depression,” “anxiety,” “codependent,” “asexual,” “attachment,” and “validation” incorrectly. Particularly “validation,” which is such an important word to understand! Validation doesn’t mean agreement. If you demand people agree with how you feel and call it invalidation when they don’t, you’re going to be disappointed, and you’ll also be wrong.

I toyed with including “ADHD” and “autistic” in the book, as these have been very misunderstood recently. I think my original chapter list had them, but I decided they weren’t being weaponized so much as they were being inaccurately self-diagnosed, which is a related but different problem. In They’re Not Gaslighting You, I really focus on how people are weaponizing clinical terms to avoid responsibility or vulnerability in their relationships. But there are lots of other examples of people misapplying diagnoses or incorrectly assigning symptoms to a disorder in attempts to explain their experience, understand themselves, or, again, have an excuse for their behaviors. This is just as problematic in contributing to the semantic bleaching of important terms and confusing people about what certain disorders actually are.

Hmm, I think I feel the beginnings of a second book, and I think I already know the title…

Improving mental health is an undercurrent in your book. With the alarming trend that more young people are suffering from mental health diseases—particularly since the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic—how can we improve our cognitive health and help others with mental health issues?

People are really struggling. We live in a very difficult world, with many realities that do notable harm to our mental health. The pandemic was such a distinct blow to our mental health and our relationships, and then social media is a lesser but persistent erosion to these things as well. And we can’t control it! We can’t erase the pandemic or take away technology, so we have to adapt.

The first thing I think everyone would benefit from is getting offline. Meet up with people at a coffee shop, not just on FaceTime. Be spontaneous instead of scrolling through reels. Go outside. Life is lived in person. We’re missing out on moments of presence, happiness, and connection by staring at our screens (and research backs me up on this).

I’d also remind people that we’re animals. We’re highly intelligent, adaptive, cognitively complex ones, but animals all the same. And animals live pretty simple, structured lives. We don’t need to give up on fun or challenges, but we need to prioritize the right things—getting good sleep, eating healthily, spending time with loved ones, engaging in hobbies and meaningful activities, and being in nature.

Happiness and health aren’t found in money, status, or even in achieving goals. Research shows that we thrive when socializing with others, expressing gratitude, and engaging in meaningful activities that allow us to be altruistic. We feel joy when we’re connected, purposeful, and kind. We should all invest more time there, and less on the other shiny goals that promise reward but often make us feel terrible.

Finally, people should seek quality mental health care. These disorders, when present, can be very hard to manage without the right help. Find a great therapist, psychiatrist, group, or program. Read books by experts. Find clinicians who specialize in what you’re struggling with. Ask loved ones for help. We live in a time of increasingly reduced stigma, so people shouldn’t try to deal with difficulties all on their own.

What creative projects can we anticipate from you to continue learning about how to improve relationships and mental health? Where should we go to keep track of your next steps?

Very ironic to be saying that after my little speech about getting offline, but people can always follow me on Instagram (@drisabellemorley) or my website: drisabellemorley.com.

I offer coaching for couples interested in strengthening their relationships, but I’m also going to add some workshops and groups. They’ll be focused on helping all those people-pleasing withdrawers who hate conflict and try too hard to keep the peace (sound familiar? That’s me!).

I’m also launching a very exciting product where I make a customized video to help people calm down during/after a tough argument. I have people answer an in-depth questionnaire and meet with me so that I can fully understand their unique emotional experience during fights, and then I create a tailored video to use to help them come to a place of calm and understanding post-conflict. Sort of like an on-demand session with me to help you pause, cool down, and return to the conversation from a place of calm and understanding.

And, after your great questions, I now have a second book to write, so keep an eye out for that someday!

They’re Not Gaslighting You

Ditch the Therapy Speak and Stop Hunting for Red Flags in Every Relationship

Isabelle Morley

PESI Publishing (May 20, 2025)

Couples therapist Isabelle Morley’s enlightening relationship guide They’re Not Gaslighting You is about understanding human behavior through a clinical lens.

Addressing the widespread inappropriate use of clinical terminology in diagnosing relationships, also known as the weaponization of therapy-speak, the book names specific criteria attached to psychological diagnoses to safeguard the actual meanings of terms like love bombing, sociopathy, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Organized by topic, it is moved along best by its comparative vignettes. Some scenarios depict valid behavior examples amplified by follow-up explanations; these are juxtaposed with examples of incorrect labelings of partners.

Diverse examples are provided to clarify which behaviors are concerning and which are natural. Researching gaslighting on the internet, the book notes, can lead to confirmation bias based on algorithms showing similar results. Further, identifying someone as a true narcissist requires that they meet at least five criteria out of nine. And beyond its advice on recognizing how disorders can be misconstrued in relationships, the book emphasizes seeking professional guidance for official diagnoses.

The prose is lucid and soothing, as with encouragements to “take a deep breath” if accused of inflammatory behavior and reassuring notes that people are “messy.” Its self-deprecating personal anecdotes from Morley’s marriage and prior relationships are also useful in differentiating between normal behaviors and clinical diagnoses. For instance, Morley’s husband could have seen her early reticence to talk finances as a red flag, but recognized it was her money stress in graduate school. The reigning message is empathetic: people are flawed, and it is better to avoid “armchair diagnosing,” which impedes introspection and healing.

They’re Not Gaslighting You is an illuminating relationship guide that encourages the clearheaded evaluation of interpersonal behaviors.

Reviewed by Katy Keffer

May / June 2025

Katy Keffer