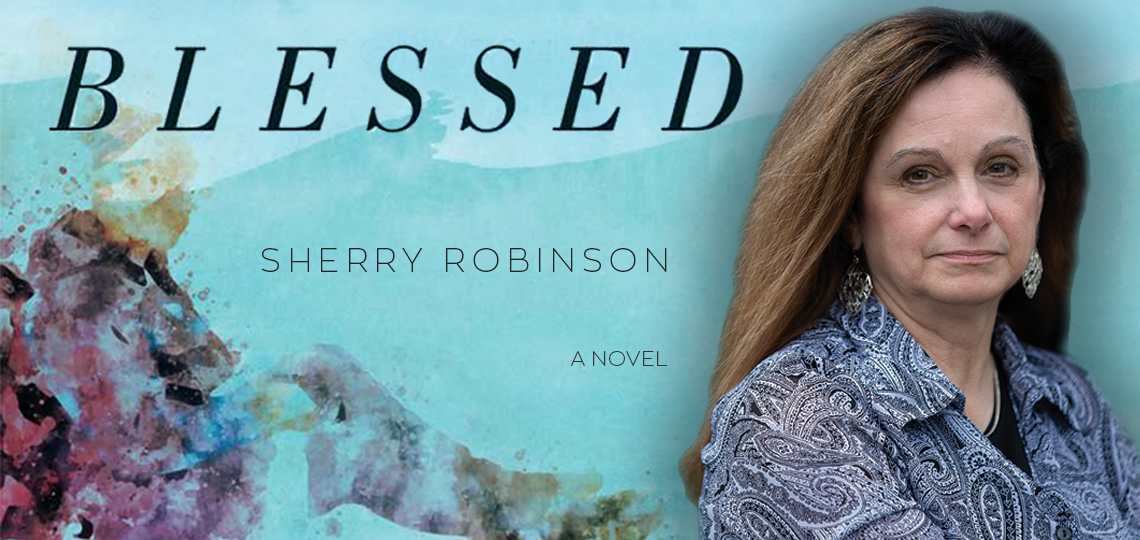

An Interview with Sherry Robinson, Author of Blessed

Talented writers are often stereotyped as being reclusive workaholics to their craft, as if writing at the highest level doesn’t allow for any distractions. In fact, writing is so mentally demanding that most writers can’t stay on task for more than a few hours a day before they need to get up from the desk and recharge. Let’s also not forget that a large percentage of published authors have day jobs. For them, writing is something to squeeze in around a work schedule, raising kids, and other demands. And that’s not a bad thing. The ability to create interesting stories usually results from the experiences gained in life’s messy playpen.

When considering the day-job slash writing-schedule of Sherry Robinson, we are reminded of Thomas Hardy’s observation that “The business of the poet and the novelist is to show the sorriness underlying the grandest things and the grandeur underlying the sorriest things.”

By way of introduction to her latest novel, be aware that as vice provost at Eastern Kentucky University as well as a food pantry volunteer in Richmond, Kentucky, Sherry is perfectly positioned to observe the human condition in all its shades. In Blessed, she tells the story of a young, charismatic preacher brought in to revive a struggling church, with tragic results. Susan Waggoner recently reviewed Blessed and called the novel “an appealing, thought-provoking work of contemporary Christian fiction.” Finally, it shouldn’t surprise you to know that Sherry’s father served as a lay preacher when she was young—further establishing her life-experience bonafides.

Enjoy the interview.

In the opening paragraphs, Blessed evokes a wholesome and hopeful tone—first, as we see Reverend Grayson’s warmth, attractiveness, and gee-whiz innocence, and then his opening sermon stressing God’s desire for us to be happy. Of course, things proceed to get more complicated from there. For the success of the novel, was it important for you to establish Grayson as a religious figure cut out of olden times?

I didn’t really think about it quite that way; it’s more like Grayson is “playing church” in the opening scene. He is trying to be what is expected of him but also trying to challenge traditional ways of understanding God. So it was important for me to establish Grayson as slightly out of step with religious figures from the past, and certainly from the figure familiar to the people in the New Hope Baptist Church. Grayson’s message is not really revolutionary, but it provides hints that he is going to nudge—maybe even push—these people toward action, not just belief.

It was also necessary to depict Grayson as a little larger than life. Religious figures can often be placed in the untenable position of being hoisted up on some pedestal with very unrealistic expectations of perfection. Sometimes religious figures can also succumb to their own egos if they have even a modicum of success.

One of the more powerful lines in the book comes when Grayson’s wife, Natalie, describes their first-date conversation about Grayson’s brief experience with atheism. She quotes him as saying, “I finally realized that my beef wasn’t with God but with some people who claimed to speak in his name. That helped me come to peace with God.” That sentiment perfectly explains how Grayson navigates the threats to his ministry. In light of the political divisions cleaving through this country, and certain religious leaders acting more as political operatives than agents of Jesus, can you tell us how these issues resonate with you personally, as well as add moral depth to the novel?

Like many people right now, I am disturbed by the deepening divide in this country. What is particularly distressing, though perhaps not all that surprising, is the role of religious people in strengthening the divide and even making it wider. Unfortunately, religion tends to be a source for division, of separating us from them. That might manifest itself on a global, cultural level, but more frequently it is localized in churches and communities. The actions and rhetoric of some people who claim a relationship with Jesus are far removed from his teachings of love, self-sacrifice, servanthood, and non-judgement, so I can understand why it might lead others to want nothing to do with God if this is how his representatives behave.

Before coming to Mercy, Grayson has learned to separate what religious people do from who God is. However, several of the people he encounters in the small town have difficulty seeing God because of their experiences, past and present, with religious people. In Grayson, though, they see something different. He doesn’t judge and he doesn’t push them toward religious structure. Instead, he just loves them. One of my favorite lines in the musical Les Miserables is “To love another person is to see the face of God.” To me, revealing God through loving others is one of the keys to moral depth in Blessed.

Grayson and Natalie’s teenaged son Tyler struggles with his sexuality and senses that his father isn’t 100 percent supportive. But with the many battles going on at the church and in the Mercy community, his son’s homosexuality is a much more complicated issue for the reverend, as Tyler comes to understand as events unfold. Christianity and homosexuality have had a contentious relationship over the centuries. Can you talk about this particular father-son relationship, as a window into Grayson’s soul?

Throughout the novel, Grayson demonstrates that he is willing to risk his pulpit in order to live out his faith. So his reticence to acknowledge or support Tyler’s sexual orientation is particularly difficult for his son. Grayson’s reluctance is rooted in the knowledge that even in more progressive churches full acceptance of homosexuality is rare. So his acceptance of a gay son poses even more of a threat to his ministry than the other issues or people he champions. In many ways, Grayson’s apparent line in the sand reminds me of how Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof cannot take that final step of breaking tradition by accepting Chava’s marriage to a gentile. It seems like a step too far.

More deeply, though, I think Grayson is uncomfortable with his own reaction. He’s ashamed that he doesn’t have the courage to openly accept Tyler’s homosexuality regardless of the consequences, and it is particularly painful when he realizes how much like his own father he has become in his relationship with his son. He is not the father he wants to be, but sadly, he comes to that realization too late.

Reverend Grayson’s number one nemesis in the town of Mercy was Reed, a longtime member of Ignite Community Church. Fiercely opposed to the changes Grayson was implementing, in addition to being openly hostile to the reverend, Reed is a powerful, unnerving force. This combustible male-male dynamic is superbly portrayed in the novel. Did you enjoy getting in Reed’s head as the story came together?

I did enjoy getting into Reed’s head, primarily because his beliefs and actions are harder for me to relate to. In order for this story to work, though, it was important that Reed’s actions come from an authentic and believable place. I needed the reader to understand—I needed to understand—that even though Reed is hostile to Grayson, he is motivated by something important to him. I don’t have to agree with Reed to understand his deep love for a woman that is like a mother to him and for a church that is part of his heritage. He lashes out, in part, because he is grieving what has been lost to him. So, I never wanted to lose sight of the underlying motivations for Reed’s actions.

Reed also needed to be a strong foil for Grayson. They feed off the masculine energy of each other—Reed usually in an aggressive manner and Grayson in a passive-aggressive manner. This power struggle is clearly what pushes the action forward.

The palace intrigue you bring to life in Mercy is fascinating but also distressing in a can’t-look-away manner, mainly because all the shenanigans take place in and around the church. Interestingly, millennials are decidedly not a church-going demographic. Do you have a theory for why this might be?

I’m a late baby boomer myself, but I suspect many millennials resist the same thing I’ve grown to resist—the church as institution. I grew up in and spent the better part of my adult years in churches similar to the one Grayson finds when he first comes to Mercy. The institutional church can find itself spending more resources and time on maintaining itself rather than doing anything for the “least of these.” The focus seems to be out of alignment with the priorities and teachings of Jesus.

I also think millennials are weary of the church—and I’m speaking very broadly here—only giving “lip service” to ministry outside the walls of the church, particularly with vulnerable populations in the community. Churches have a tendency to focus inward, with a “take care of our own first” mindset. Several years ago, I even heard a few congregants complain that the pastor was preaching too much about the poor. That alienates millennials—and me as well—and it makes them question the whole point of church. Many of the characters in Blessed who turn away from church do so in large part because they perceive a lack of authenticity there.

The very first sentence of Blessed announces the death of the central character. What was the reasoning behind this choice and how did that choice influence the structure of your novel?

I wanted this novel to play with the concepts of perception and perspective. How we feel about a person depends in large part about what our interaction with that person is like, but it also depends on what our own background and experience has been. So it was important for the main character to be developed almost entirely from the points of view of other people. It made sense, then, to pull Grayson out of the picture immediately. In this way, his story can be told as it is perceived by the people he encountered.

Will you let us into your head as a writer? What storylines interest you? What do you read for pleasure?

I am most interested in stories that examine complex relationships or that push me to examine an issue in a new or deeper way. For example, in Silas House’s newest novel Southernmost, the reader must at some level grapple with a cultural bias that renders a father kidnapping his own child more harshly than a mother doing the same thing. Those are the stories I want to read and those are the stories I want to write.

When I get a chance to read, I gravitate toward Southern writers. That’s probably still a bias from my graduate studies, when I focused on Southern literature. So I’ll read Silas House, Lee Smith, Tayari Jones, or other contemporary authors, and sometimes I’ll even revisit some classic William Faulkner or Flannery O’Connor. I love a good Southern Gothic.

Are you currently working on a new project?

I’ve just begun work on a new novel that picks up the story of one of the characters from my first novel, My Secrets Cry Aloud. That character leaves her family—her husband and three young daughters—and it’s clear that she hasn’t come back after sixteen years. I want to explore why she doesn’t come back. I think this is going to be an exploration of how fear influences the choices we make.

Sherry Robinson, Blessed, Shadelandhouse Modern Press, 978-1-945049-10-1, Smpbooks.com

Matt Sutherland