A Reviewer-Author Interview with William Viney, Author of Twinkind: The Singular Significance of Twins

We have twins on our mind today, thanks to an interview between reviewer Rebecca Foster and William Viney, author of Twinkind and one of the world’s foremost experts on siblings who share wombs.

But before we go to that conversation, let’s briefly peek into the future to learn how AI may help us all become twins. Seriously, because it’s long been a dream of researchers to do things like create an exact replica—a digital model—of the heart of someone with rare or difficult-to-treat conditions so as to practice different what-if scenarios using new procedures and medical devices. In fact, that dream has been achieved in the Dassault Systemes’ Living Heart project and the technology is being used in hospitals around the world.

Dassault and other tech companies are now working on digital organ twins for the human eye and even the brain. The expanding use of sensors to connect physical things to networks allows scientists to build things digitally that will constantly learn from and improve its real counterpart. And AI will only help those efforts exponentially. A spokeswoman for Dassault says, “At some point we will all have a digital twin, so that … we can increasingly make preventative medicine, and make sure that every treatment is personalised.”

Enjoy the interview.

You yourself are a twin, and your brother, George, contributed the book’s foreword. Do you think only a twin can really understand what this relationship is like, or have you read novels and/or seen films by non-twins that you felt were true to the experience?

I have found that the world’s myths and religions, arts and sciences, have very different ways to see and use twins. But what they might have in common is that twins are different to other humans—magic, malevolent, maybe not human at all. This has been reinforced in my everyday interactions. We are asked, “what’s it like to be twins?” as if being twins is beyond imagining. I also have reasons to doubt my relationship is like the twin relationships of other twins. After all, it’s a relationship that is never entirely mine, and it connects us to a history of twins and twinning that is as long and complex as human history.

I don’t think twins experience the social category of being twins in the same uniform, universal, and unchanging way. My own relationship with my brother, for example, may have been formed in the 1980s and 1990s, but has developed over time. It has responded to our life circumstances and has never been singular or “true.” It is this paradox of difference which leads me to feel that the truth of twin experience is like its value—a matter of perspective.

(I can’t miss the opportunity to recommend the novels of Ágota Kristóf, The Notebook Trilogy, Michel Tournier, Gemini, and Bruce Chatwin, On the Black Hill—they explore changing and challenging twin relationships.)

The book is so wide-ranging, covering science, mythology, medicine, and popular culture. How did you gather all the information you needed and avoid being overwhelmed by the topic as a whole?

As an academic researcher working at different UK universities, I was lucky to have fellowships and work with academic and artistic colleagues. All had enormous expertise in their areas of research and could guide me to where twins were important in their work. I met people who had read deeply in philosophy, history, anthropology, biomedicine, and other fields. This is how I became interested in how twins shaped old and new ideas of life, liberty, technology, violence, and entertainment. But less formally, I found that everyone I met would share something different about twins. Lots and lots of people would offer their thoughts and theories and stories about twins—parents, teachers, doctors, lawyers, and other professionals, and, of course, twins themselves were a constant source of wisdom and guidance. Even after the book was printed, I found notable or notorious twin pairs, sub-types of twinning, and new areas of twin-related science; it never ends. The topic is overwhelming in the same way that human culture is abundant. In the end, there are deadlines, word limits, licensing budgets—no book can be comprehensive.

One section is about the data that twin studies have generated. Our understanding of diseases and social phenomena owes a lot to this research. Can you give some examples of the insights that twin studies have contributed?

Scientists that use twins in their research are driven by the apolitical fantasy that twins are “natural experiments” and “living laboratories”—treated as opportunities to practice a particularly powerful kind of empirical thinking. Approximately 1.5 million twins participate in studies worldwide. A whole industry has evolved, making twins unique subjects in big data science and the history of that science. Biomedical researchers have done much in the last 140 years to make twin identities genetic, and to suggest that twin relationships are best explained by biology.

We owe important concepts and vocabularies about health and wellbeing to twin studies—such as the idea that we can try to measure (and predict) how much a disease or trait owes its cause to nature (biology) or nurture (society). Twin studies have used a set of standard statistical models to measure the causes of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, epilepsy, autistic spectrum disorder, and mental health conditions such as schizophrenia, as well as complex behaviours such as political beliefs and voting patterns, telephone use, nail-biting, and even pet ownership.

Twin data has been used to guide the development of new drug treatments and social interventions, but it has also been used to put targets on the backs of the most vulnerable people in human society. Twin data was used to justify the eugenic eradication of groups of people in Europe and North America throughout the twentieth century. It was used to support racist pseudoscience like Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve (1994), which argued that white Americans and Asian Americans have inherently higher IQ scores than African Americans. I think we should look beyond scientific breakthroughs and consider how twin studies shape our political values about people, populations, and statistics.

There are dark aspects to this story: certain places and times where twins have been considered taboo; twins’ involvement in crime; and beliefs about their participation in the paranormal. In the interest of being balanced and comprehensive, you’ve written about all of these topics, but how did this material make you feel?

It strikes me that this is a personal and impersonal story, where what I have learned has strongly shaped what I am able to feel about twins. I have been a participant in biomedical twin research for ten years. Learning about its eugenic and racist history made me rethink the power, neutrality, and scientific rationality invested in this field. But I do not—and I guess I can’t—feel an affinity with all the twins or aspects of twinning that I present in this book. I am less connected to the criminal or parapsychological past, and I find it difficult to feel a close sense of involvement with these parts of the book. And yet they all share in an economy of twin sensation and excitement that I observed frequently when I was doing my research, often accompanied by a wide-eyed excitement at twin potential that has led them to sell their stories or have them stolen. I felt caution and responsibility towards the people I was writing about, not wanting to further sensationalize their lives or misappropriate material. This ethical challenge was intensified by wanting to include twins from all regions and backgrounds.

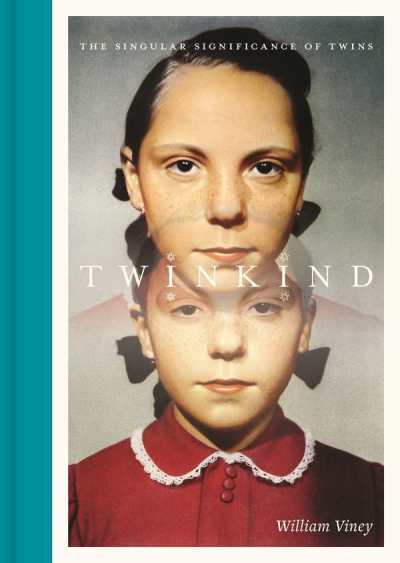

The book is full of striking examples of twins in art and photography, from antiquity to the present day. How did you go about amassing the illustrations, and to what extent did they dictate the contents? (Did the text follow the images, or vice versa?)

This is the most collaborative book I have been involved in. I wrote a draft of the text and handed it over to the editorial team with about 150 images I thought would illustrate each section. Many of the images I collected over 10 years of research. Twin pictures can be striking, but there are many ways to represent twins in history, without presenting the heads and shoulders of two identical faces. I was eager to include ethnographic objects, totems, statues, and votives that serve as proxies for twins. Some of the images I suggested turned out to be unavailable or difficult to source in the right formats, and so substitutes were found. The publisher added a further 250 images to produce a first set of layouts, matched to an overall thematic design we agreed on from the beginning. There were gaps and overlaps. Some spreads we agreed worked very well, while there were other images that I could use as a prompt to seek others. It was a process of refinement and negotiation; a back and forth between text and image, author and editorial team. But the aim of the images, and the aim of the project overall, was to try to represent the history of the world’s twins in a single, beautiful book. Variety, diversity, and the unexpected were our guiding values.

Rebecca Foster