A poignant and compelling exploration of identity, personal growth, and the enduring strength that comes from embracing one’s purpose

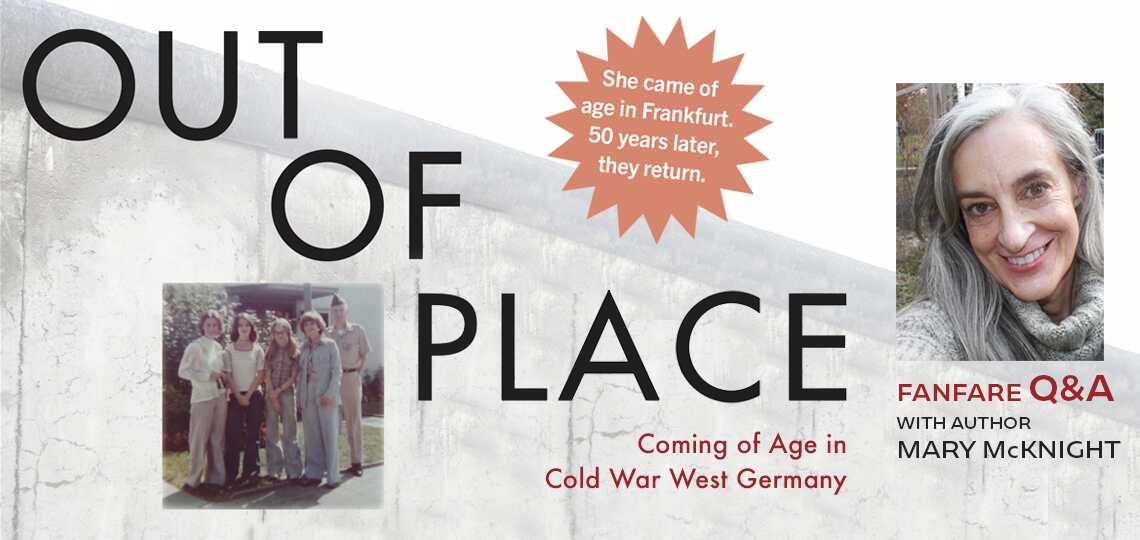

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Mary McKnight, Author of Out of Place: Coming of Age in Cold War West Germany

Joining the military is the one form of government service requiring that one puts their life at risk. And, along with those unselfish, often heroic service members, their spouses (mostly women until recent times) and children were often stationed along with their father and sacrificed what might be called a “normal” life for a nomadic lifestyle. In the mid-1970s, it was the mother who was the glue that held the family together as they traveled all across the USA and overseas to whatever duty station (not on a Hardship tour like Vietnam) when their father was given Orders to move at a moment’s notice.

Today, we’re with Mary McKnight, a self-described Army Brat who, along with her two sisters and mother, were stationed with their Army COL father for a three year tour in West Germany during the tense years of the Cold War. Mary’s Out of Place covers that time abroad and reflects on how the experience shaped the rest of her life—from girl on the cusp of young woman, first loves, to the various musical genres greatly influencing her openness as there was only one American radio station, to learning about and immersing herself in other cultures through travel, going to school with multiethnic fellow Brats to finding her place as a feminist in a highly patriarchal society.

We discovered Mary’s story after reading Meg Nola’s glowing Foreword Clarion review and quickly put the two together for an engaging conversation.

You stayed in a nice, spacious home while your father was stationed in Frankfurt, but decades later, you learned that a huge bomb from World War II was found buried in the house’s backyard. So, essentially, throughout your three years in Germany, you and your family unknowingly lived with the potential threat of explosive obliteration. Did this discovery prompt you to write Out of Place or had you been contemplating the idea prior to that event?

I found out about the bomb (discovered in 2017) about two years after I started the book. In 2015, my then sixteen daughter had a stroke and was wheelchair bound. Doctors didn’t know if she would recover, but I retired from teaching a year early so that I would receive some money. (That’s a whole story in itself. Suffice to say that all the BS about “We look out for our staff,” was, let’s just say, a lie.) I had horrible insomnia, as I took to being in her bed with her—to make sure she would stay alive, be available to take her to the bathroom, help her turn, and many other caretaking things—hoping upon hope that she would recover.

I began the book by wanting to return to a place where I felt “safe,” because I was a ball of complete anxiety over my daughter’s health on the inside. That place was Frankfurt, Germany. I looked online first for coming-of-age books about that time period and in each one, the girl had suffered some horrible tragedy, like cancer, or having an arm bitten off by a shark. It really angered me as I found that all a man had to do was write about their growing up years, an old baseball mitt, and it was an instant “classic.”

I started, via YouTube, listening on earbuds to music from my era (1974–1977) and the stories came flooding back. They were in no special order, at first, just whatever I happened to remember. No editing, just stream of consciousness of memory. I am a highly empathetic, middle child, sandwiched between two sisters, and I am the “keeper of the stories” of our lives.

I began to realize that I had, could it be, a book? I reached out to The Manuscript Academy and Julie Kingsley connected me with the unbelievably perfect match of author, instructor at the Stone Coast Writing Program in Maine, Susan Conley. She read through what I had, my first draft, and said, “You have what most new authors struggle with, finding your ‘voice.’ You have that. Now, I need you to ‘banish the censor.’” She did not criticize, she asked me questions, such as, “What were you feeling when that happened? Put us in cinematic scene. Let us as readers be there too.”

She took it from first draft to final with such grace, and truly, there would be no book without her. She said to me once, when I was struggling, “It’s all inside you. You know it’s there. Just let it out.” Whew! Not easy for someone raised to stuff it all inside. But, I trusted her, and I let it all out.

You note how being an Army “Brat”—the nickname for children of American military members—was quite different than being the child of a civilian family. What was expected and how did that code of behavior affect your later life?

Before we would leave the house, we were always reminded, “You are ambassadors of our country. Your behavior affects your father’s career. You are to use your best manners and live as though we are constantly watching you.” Sheesh, talk about pressure! Imagine being thirteen years old and having the responsibility of your dad’s career trajectory on your shoulders! No wonder I’m still in therapy!

As for the life of an Army Brat: I can talk to anyone, I value other cultures and ethnicities, and I was brought up to believe that we are all human. I am neither above nor below anyone. Now, let’s talk about relationships and friendships. I am terrible at both. It was great after six months to three to four years to leave all my troubles (and that included people) behind. These were the days of airmail communication and expensive long distance calling. So, this played out in my adult years as … well, as my mother once said, “Mare, you’re just unlucky in love.” I am more like a hermit who knows how to be an extrovert when the situation calls for it.

You describe your parents with such memorable and engaging detail. Your mother approached “the world with sparkling optimism,” her “swanlike neck” “sprinkled with Jean Naté perfume.” Your father had his military crew cut trimmed weekly, buffed his shoes “to a glassy sheen,” and in general “conducted his life with detail, expectation, and honor.” You also note how your father gave your mother a book called The Army Wife after their engagement and that she followed its advice faithfully. But how did The Army Wife’s guidance contrast with the burgeoning feminism of the 1970s?

Total clash. Mom was so smart. I mean, that woman could write the most beautiful postcards, thank you notes, notes of condolence (she copied quotes she loved), and yet, Dad had the “final word.” It made me so mad (internally) that she wasn’t “allowed” to speak up. I swore, I would never be like that, and son of a bitch, I turned into that. I morphed myself, squashed my smarts, talents, desires, wants, just to please men. Mom did drop a few memorable lines when we lived in Frankfurt and my interest in boys skyrocketed. “Men are a dastardly lot.” And my personal favorite, “Men, are a disappointment, oh, except for your father.” Great, I was doomed to be alone.My memoir evokes so much of the awkward sensitivity of adolescence, along with the heightened feelings of teenage excitement and newness.

Feminism was a forbidden subject as it was portrayed as “the end of the family.” Mom did share that when I was a baby, a former neighbor of theirs in Altus, Oklahoma, Martha Wood, gave her The Feminine Mystique, by Betty Friedan, and she (Mom) recommended I read it, “But don’t let your father know.”

Though you did keep diaries at the time, you discarded them when you moved back to the United States. Was it difficult to piece together those youthful memories and delve back into the intense emotions?

The music I referred to earlier (because I listened to records on our stereo which I still own!), brought me right back to those moments. Smells, sounds, tastes, words, all elicit memories. I have played my life through my soul, all my life. My earliest memory is age two. Mom taught me to be a listener—okay, some might call it eavesdropping, but she said you can learn so much about people by listening. It has served me so well as a writer, and I found that the more I wrote of my time overseas, the more I remembered.

I cried as I wrote some of the stories, as we had been taught to stuff our feelings inside and always wear a “pleasant face.” But, as trauma work has now taught me, the body remembers. Well, my body/mind has done an exceptional job and I had stuffed down a shitload of stuff. It was a total catharsis and—my Developmental Editor Susan Conley couldn’t believe I did this—I let my dad read it before I went looking for a publisher. I figured if I couldn’t stand him reading it, I wouldn’t be able to stand a negative review. He corrected some of my information considering the rank or assignment of a particular person, and then said, “Good job.” Highest compliment ever!

My mother had memory loss and by the time the book was in the final format, she didn’t even know my name. She died in March 2024, and Dad died five days after her funeral. Neither got to witness the publishing of my book, our book. When I touch my copy of the book now, I always kiss it. Without my parents, I would not be me. Yes, my dad made me crazy as a teen, and Mom frustrated me when she would give Dad the last word. And as I aged, I realized just how damn lucky I was, to have two people who loved each other, respected each other and taught us to treat each person with respect, kindness and to remember that everyone has a story.

You regularly tuned into the American Forces Network while your family lived in Germany, listening to the “eclectic” playlist of rock, soul, “classical, jazz, and country” music. In that era before the internet, YouTube, and Spotify, how was being able to hear that station on your portable transistor radio so important?

That little radio (which I still have) revealed music which took me to places I never would have known. It made me a world listener and I just assumed everyone in the world (especially our country, the USA) was going to be the same way. Suffice to say, upon return to the States, I learned that prejudice, division, and hate was alive and well. On that transistor radio, I would wait and wait for a favorite song and while I waited, I heard other groups and types of music and it all became “my music.” Oh, when I hear Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book songs (I still have the album), they were my songs, as well as Led Zeppelin. Now, I wasn’t allowed to buy Led Zeppelin as my father forbade it; I could only hear it on my radio or over at my best friend Jenny’s house.

I love being a person who can easily listen to reggae, and feel it is a part of me as easily as Linda Ronstadt. There’s no difference for me. Sure, it’s a different sound, but it’s music. Music is part of my DNA. When Sting sings, “If I ever lose my faith in you …,” it’s just as powerful as Barry White singing, “You’re my first, my last, my everything.”

What were your general impressions of Germany during the mid-1970s, amid the continued postwar rebuilding and Berlin Wall division? Would you like to revisit the country?

Germany was a welcoming country. The people, the food, the store clerks, restaurant waiters and waitresses, were so much more understated than we were used to from American culture, but I never felt unwelcome. When we visited Fulda (a place where the Berlin wall was barbed wire and land mines) and Dachau Concentration Camp, I had no previous working knowledge of World War Two. We hadn’t studied it in school before I went to Germany, and while we were over there, I never learned about it … until my first German teacher made it his mission for us to visit locations (the site of a Nazi book burning, pointing out rubble still from the war) and to also see the beautiful culture of the German people. I mean, I was a teenager, and talk about an egocentric period of life! If I could get my hair to cooperate, it was going to be a good day. Damn, that sounds so shallow, but it was true. It was only upon all my research (and I did hours of it while writing, my publisher cut a huge portion out of the resources/endnotes sections) that I learned of the atrocities.

Did you feel a certain sense of closure or healing after finishing the memoir? Are you working on any new projects?

Great question. I felt a compassionate understanding of my older sister, who, when you read the book, was horrible to me and the source of the majority of my insecurities for years and years. Writing the stories helped me see that she was just an insecure teenager. Today, she is truly saint-like and my biggest fan. Incredible.

I also saw my dad in a different light, once I had my own child. Now, would I raise her like he raised me? Hell, no! But she is so much like him, and they had the most incredible bond. It was a joy and an unexpected pleasure to learn a side of him which I never knew existed. I finished the book, and immediately played “It’s My Turn,” sung by the incredible Diana Ross.

I began to dream again of the promises I had made to myself as a girl growing into a young woman. And here I am at the age of sixty-four, with no relationship/partner, living, renting a house built in 1898 filled with treasures from both my parent’s home and my paternal grandparent’s home, along with some things that were mine I had purchased at various times in my life.

This book, this memoir, is for all women, and for men who have the courage to learn what we go through to become women.

I am afraid to return to Germany as I fear I will just cry over a life that does not exist anymore. The house we lived in was torn down sometime after the bomb was dismantled and a new one built in its place. Seeing that in person would shatter me.

But I loved Germany. I loved all the travel. (Even though at the time, I complained and acted like the young teenager I was). I am forever thankful to have had those three years.

I just finished writing a rom-com called Time after Time. It is a second-chance-at-romance book for a couple who fell in first love, at ages nineteen and twenty-one. Okay, so the characters are based on me and my first love, but the story is all fiction and was beyond fun to write because I could make the characters do anything! I’m halfway through the sequel—as the main characters and also the supporting characters, had more to tell/more to do and one book just wouldn’t cover it. Oh, and I’ve written two books for children based on my daughter’s two favorite stuffed animals. Yes, I’m searching for a literary agent who will be my partner in growing my writing career.

I’m in that new category of “Late in Life Debut Writers” and whomever is reading this, please know that my rom-com is complete, the sequel is halfway completed and I have so many stories kicking around inside me (some in partly written form, some just floating) and I need a chance. I will not disappoint!

At the Frankfurt Buchmesse, in October 2025, my memoir—that’s right, my stories, fifty years after I left—are returning and being represented at the Book Festival! I am stunned, honored and, okay, am hoping it is “discovered.”

Thank you for this interview and the chance to tell my story.

Out of Place

Coming of Age in Cold War West Germany

Mary E. McKnight

She Writes Press

Clarion Rating: 4 out of 5

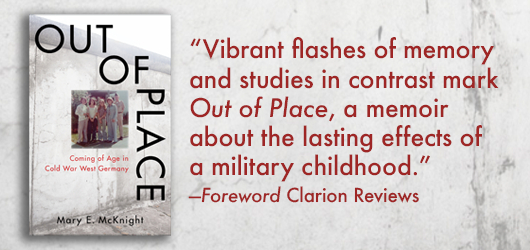

Vibrant flashes of memory and studies in contrast mark Out of Place, a memoir about the lasting effects of a military childhood.

Mary E. McKnight’s expressive memoir Out of Place recounts her early adolescence as an American military child in 1970s West Germany.

In 1974, McKnight and her family began a three-year stay at an American military installation in Frankfurt, Germany. McKnight’s father was a civil engineer and a Vietnam veteran; McKnight, her mother, her sisters, and the family cat were accustomed to relocating for his assignments. As a military wife, McKnight’s mother followed her husband’s lead and maintained a pleasant home environment; as military children, McKnight and her sisters were encouraged to set a good example and be resourceful, resilient, and stoic.

McKnight turned thirteen soon after arriving in Frankfurt, and the book captures her adolescent awkwardness and emotional intensity. She and her sisters attended American-run schools with the other children of military personnel. Despite being placed in a new environment at a time of significant personal change, McKnight did her best to acclimate. She also began to question her mother’s submissiveness and to nurture her own burgeoning feminist consciousness, even while admiring her mother for her compassion and capability. Her father, in contrast, is captured as loving but more brusque—a figure who “conducted his life with detail, expectation, and honor.”

Vibrant with flashes of memory, the text covers McKnight’s first meaningful romantic crush, favorite songs playing on the radio, and the beginning of summer vacation. McKnight wobbled about on platform shoes, yearned for “hip-hugger jeans,” and made daring fashion choices despite her older sister’s jeering. And the period and setting are captured via contrasting impressions of Germany being shadowed by Nazi atrocities and divided by the Berlin Wall on the one hand and of the country’s distinct architecture and cultural heritage on the other. These factors are weighed against sights from the family’s travels: the Parthenon is “framed by the cloudless blue sky”; Neuschwanstein Castle is like a fairy tale; Dachau is overwhelming, marked by “deep sadness” and a sense of the dehumanizing cruelty it represents.

The narrative alternates between introspection, candor, and mellow rearward gazing. It is intimate at times, as where it expresses lingering anguish over personal pains, including a mediocre grade on an art project, sibling angst, and the lasting influence of the family’s code of stoicism. At times, as when it seeks connections between McKnight’s toxic romantic relationships in adulthood and the lessons she learned in childhood, it becomes discordant, its sense of deep unresolved pain clashing with its general focus on McKnight’s coming-of-age.

Out of Place is an engaging memoir about the propulsive energy of a 1970s youth spent abroad.

Reviewed by Meg Nola

September 26, 2024

Meg Nola