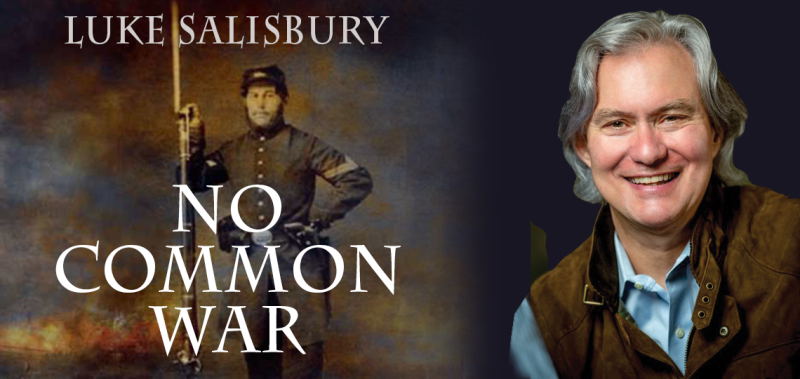

A Conversation with Luke Salisbury, Author of No Common War

The heartbreaking George Floyd killing in Minneapolis appears to be one murder too many for this country’s conscience and we’re finally going to have the honest conversation about race we’ve been avoiding since the end of The Civil War. That chat will require a reckoning with all the ways discrimination permeates our society. Lasting reconciliation means laws must change, reparations paid, investments made to remedy centuries of mistreatment. We can and must do this as a nation.

Part of the process of identifying discrimination in all its forms is to study history and there’s no better place than literature to help us understand how different eras and episodes shaped us as a nation. Today, we’re privileged to hear from Luke Salisbury, the author of the superb new Civil War novel, No Common War. In her review for Foreword’s March/April issue, Susan Waggoner points to the lasting effects of the war, “Those who leave to fight never return the same … the North is seen mourning for its lost innocence just as the South does. The book perfectly captures the pitch of the national upheaval and its emotional traumas.” She finishes by paying the highest of compliments, “Beautifully written, No Common War ranks as one of the best war novels in decades.”

Thanks to Black Heron Press for helping us connect with Luke for this interview.

The opening chapters detail a simmering standoff between Mason Salisbury and his son, Moreau, over the just announced war and Moreau’s resistance to fighting for pacifist reasons, even as he fiercely despises slavery. Mason finally prevails when he introduces Ro to an escaped slave, Gib, on his way to freedom in Canada. No doubt, many young men from northern states had no firsthand experience with the institution of slavery. Give us a sense of what they were fighting for, in all of its variations?

At the time of the Civil War many northerners did not have firsthand experience with slavery, but anyone in Central or Northern New York State certainly knew about Abolition. Abolitionist speakers traversed the state speaking in the theaters and lyceums in any town of any size. Central New York was known as “the burned-over district” because of the red-hot rise of evangelism known as the “Second Great Awakening” that started in the 1820s. The area saw the rise of Mormonism, Seventh Day Adventism, Shakerism, Women’s Suffrage, Spiritualism, utopian communities—and much of this furor went into Abolition. Frederick Douglass published his North Star newspaper in Rochester, NY, which was a major stop on the Underground Railroad.

Many people in the North Country, like Mason Salisbury, were involved with the UGRR. Everyone in that part of New York, and the whole country, had an opinion about slavery. The argument Mason and son Moreau have about fighting for Abolition as opposed to the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” would have happened between many fathers and sons. Many Union soldiers made it clear they were not fighting for “n-words.” This is an important part of the novel—quite dramatically so the night before the battle of Antietam.

Cousins Moreau and Merrick are attached at the hip after enlistment as they train and head to war with the 24th New York regiment. Was it common for family members and friends to serve and often die together in the Civil War?

Cousins Moreau and Merrick Salisbury enlisted together and served with their neighbors in the 24th New York Volunteers. This was common in the Union Army, especially at the beginning of the war. Even more so in the Confederate Army where troops were raised locally. Fighting with your relatives and neighbors helped unit cohesion and willingness to sacrifice. If you were going to run, you hoped everyone else did too, because the folks back home were going to hear about it.

The first weeks of any war contain a sense of optimism—for combatants and civilians alike—that things might be over very quickly. The Civil War was no different. Does this speak to blind faith, or did the Union and Confederacy truly not recognize the formidability of their opponent?

Optimism is rampant at the beginning of wars, and particularly the Civil War. It’s the first war with advancements of the industrial revolution. Railroads transported and supplied much larger armies. Cannon and rifles were much improved and mass produced. At the battle of Antietam, which is the center of No Common War, more men were killed in one day than in all the wars America had fought up until the Civil War. No one could foresee the brutality of the war.

The North thought it would win quickly because its economy was five times larger than the South’s. Northern armies were bigger. Confederates believed they couldn’t be beaten because of courage, Southern honor, and fighting skill. Mark Twain blamed this attitude on Walter Scott—the notion one brave man with a plume in his hat could defeat any number of lesser men. The Civil War, with its massive armies, huge battles, enormous casualties, (1.2 million in a country of 30 million) is the first truly modern war.

The novel notes that southerners viewed the war as the second American Revolution, and that by gaining recognition from England, their chances of winning the war would improve significantly. Can you speculate on how England’s involvement might have played out?

Southerners viewed the war as the “Second American Revolution” because they were fighting for their freedom. That freedom, of course, was the right to own slaves, and not be told what to do by the Federal government. The latter issue echoes to the present day. The first American Revolution could not have been won without the help of the French, especially the French fleet that trapped the British Army at Yorktown. The “Second America Revolution” could not have been won without the British Navy breaking the Union blockade and allowing the South to sell cotton to England.

Given the political situation in the North, had Britain recognized the Confederacy, there might have been peace between North and South. There were elements in the North that urged letting the “cotton republics” go and “Peace Democrats” who didn’t want to fight. How long this peace would have lasted is debatable. Would the North have kept fighting? Would Lincoln ever have accepted the break-up of the country? Would he have been re-elected in 1864? Mackinlay Kantor’s If The South Had Won The Civil War is full of interesting speculation.

To imagine a battle scene, let alone describe it credibly, has long been one of literature’s most difficult tasks, but one you executed exceedingly well. How did you prepare? And also, beyond the battlefield, you didn’t shy from describing the peripheral horror that takes place when hardened soldiers come in contact with civilians. Are these scenes difficult to write?

The 24th New York Volunteers fought four major battles and many skirmishes over the summer of 1862 culminating in the bloodiest day at Antietam. I had much combat to describe. It’s difficult to create the chaos, fear, noise, sweat, and action of battle on the page. I did not serve and have no first hand experience of war. My father and both grandfathers did. They didn’t talk about it, but there was a profound and ominous sense of war in the family.

Writing about combat took much research, re-writing, energy, and imagination. It’s not easy. Writing in the first person helps. Atrocities happen. Rape happens. No Common War doesn’t dwell on these, but they aren’t ignored. Both Salisburys were wounded so medical care was important. Civil War medicine was as brutal as the fighting—usually amputation and frequent death from infection. Screams, piles of arms and legs, blood curdling in pools under amputation tables were the aftermath of a battle. Soldiers said the surgeon’s tent was worse than battle. It was a vision of hell—and very difficult to write about.

Returning home was another battle in itself. Describing Moreau Salisbury’s return, and what we now call PTSD, required imagining the effect on family, particularly the women. Wars can’t be fought without home, and that story can be brutal too.

What is it about the Civil War that compels you to devote years to research and writing? Is there something in particular about the war that you would like your readers to take away?

My fascination with the Civil War started with a pair of boots. A pencil was stuck through a hole in one. They were worn by Moreau Salisbury at Antietam. I used to play with them. Grandpa told me his father saw the face of the man who shot him. You don’t forget that. The older I got, I realized how remarkable it was I knew a man, and knew him well, whose father fought in the Civil War. Whether or not you have relatives who fought, the Civil War is pivotal.

Gore Vidal said the Civil War is the American Iliad and Odyssey. Heroism, blunders, strategy, sacrifice, suffering, grief, homecoming—it is the American story. And it isn’t over. This is a sad truth. Look at the protests in 2020. Look at any inner city. The legacy of slavery, the failure of Reconstruction, the Civil Rights struggle, red versus blue states—which is virtually Blue versus Gray—bedevil us still. The opening scene of No Common War will resonate. I guarantee it. I hope readers will come away from the novel with a better understanding of the war and its relevance NOW.

What’s next for you and your pen? Are you currently working on something?

No Common War is the first of a trilogy of novels about the Salisbury family. Moreau’s son, my grandfather, became a military surgeon, serving in both World Wars, and wounded in the First. The second book is also the story of my grandmother’s two marriages. I once asked Grandpa how they met and he said, “I was the best man at her wedding.” What? Thereby hangs a tale and it’s a good one. The Broken Charm of The World is a love and war story.

The third book is about my father and his brother in the Second World War. Dad wanted to be a Conscientious Objector but volunteered for complicated family reasons. He went Missing in Action in January 1945. He had been badly wounded and taken prisoner. He weighed 98 pounds at liberation. His brother Mason, a tank commander, winner of the Silver Star, Yale crew captain, committed suicide after the war. Three generations. Three wars. Men who went for different reasons, and suffered, with their families, in hard ways. These books follow an American trajectory of service and consequence. An America that may be vanishing.

No Common War

Luke Salisbury

Black Heron Press

Hardcover $27.99 (315pp)

978-1-936364-29-9

Luke Salisbury’s stunning Civil War novel No Common War brings America’s bloodiest war to life through the eyes of a father, a son, and those who care about them.

Mason Salisbury, a staunch abolitionist, has seen the cruelty of slavery first hand. His son Moreau, called Ro, is an equally staunch pacifist—until he befriends a runaway slave. After Fort Sumter, Ro enlists and marches off to war with other young men from his small town in upstate New York.

Though it is narrated by both son and father, Ro emerges as the book’s main character. Also taking the stage are his mother; Merrick, his cousin and fellow soldier; Helen, the girl he leaves behind; his uncle Lorenzo; and several fellow soldiers with whom Ro grew up and forms tight bonds. These characters are drawn from Salisbury’s family stories; they are dimensional and complex from the first, and anxiety over their fates propels the story.

The text recreates battle scenes in granular detail, etching them in acid. It captures the isolation of soldiers within their own tiny cadres, picnickers who turn up to watch the first battles but leave disappointed at the lack of fierce fighting, and families traveling by wagon to battle sites in hopes of identifying and retrieving their dead or wounded kin. Such sharp details build a sense of realism that ratchets up tension each time Ro and his comrades take the field.

The effects of the war on families at home are clear, too. Those who leave to fight never return the same, and the North is seen mourning for its lost innocence just as the South does. The book perfectly captures the pitch of the national upheaval and its emotional traumas.

Beautifully written, No Common War ranks as one of the best war novels in decades.

SUSAN WAGGONER (February 27, 2019)

Matt Sutherland

![Luke Salisbury No Common War DaVinci Eye Award Finalist “I’ve read very few novels that I found difficult to put down, but this is one of them…[I]t’s that compelling!”-LawrenceKessenich House Literary Review Order Today](https://www.forewordreviews.com/foresights/art/80365-w600.jpg)