It looks like you've stumbled upon a page meant to be read by our code instead of viewed directly. You're probably looking for this page.

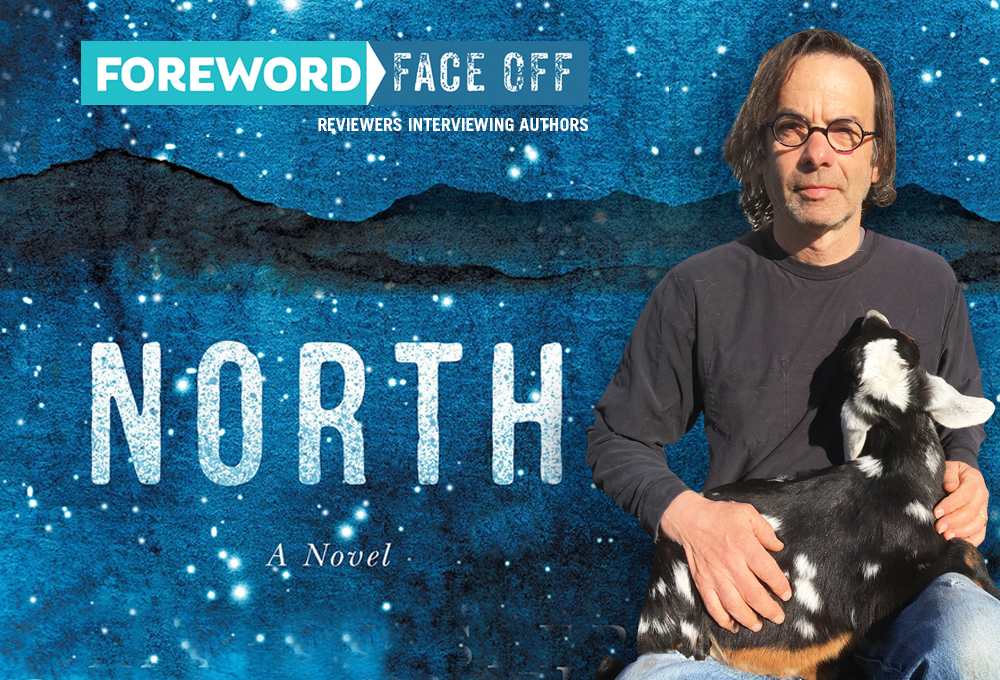

Reviewer Meg Nola Interviews Brad Kessler, Author of North

Look back over the past twenty five years or so and put your finger on some of the ways society has changed for the better. LGBTQ+ rights, for example. Would you have guessed that gay marriage would be overwhelmingly accepted now, when polling from the late nineties showed it deeply unpopular? What changed?

As we hope for similar miracles to take place in other dark corners, we naturally look to the artists among us to help open hearts, just as they have throughout history. Novelist Richard Powers said recently: “I do believe that the arts are absolutely instrumental in any kind of cultural transformation unfolding on any scale.”

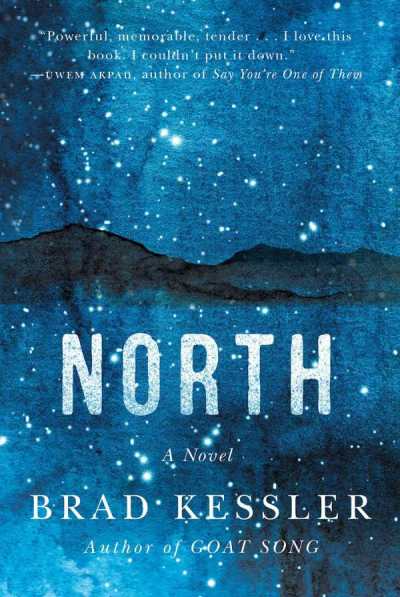

In his new novel, North, this week’s guest, Brad Kessler, offers a primer on how artists embrace their role as agents of change. In the book, he showcases extraordinary insight into matters of religion, racism, migration, and misogyny—quite the big four—and even the most hardened partisan will find themselves moved to reconsider their beliefs.

In her starred review for Foreword’s September/October issue, Meg Nola calls the book “compelling and compassionate”—just the confirmation we needed to put the following conversation together.

Was there a particular moment of inspiration that started you on North, or was it more of a gradual development process?

North developed gradually over the course of a decade. I live beside a monastery and hear their bells each evening and I wanted to write a novel that took place in a similar type of mountain refuge, a hushed and sacred place that existed almost out of time. I was interested in the idea of sanctuary, of finding a safe place in the world. At the same time—it was around 2011—the refugee crisis in the Middle East and North Africa had escalated into previously inconceivable proportions. What safe place, what sanctuary, did these millions of people have once they’d lost their home?

So the two strands began to emerge side by side, the local and the global, the story of a monk on my mountain and the one of an asylum seeker fleeing from the Horn of Africa. It was the intertwining of these two stories that formed the nuclei of the novel but it took years to find out who these two characters were, Sahro and Christopher, and what their story would come to be.

Teddy Fletcher is the groundskeeper for the monastery, and a veteran of America’s involvement in Afghanistan. He suffered life-changing physical wounds while deployed, and he has some understandable post-war psychological issues. How do you think Teddy would feel about the United States’ recent withdrawal from the region?

He’d be heartbroken and troubled but not really surprised by this final chapter of a failed war. By the time we meet Teddy Fletcher it’s 2017 and he’s long been disillusioned about the US mission in Afghanistan. He’s had the hindsight of witnessing the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—the Global War on Terror—and seen firsthand how much pain they’ve caused and how little they’ve accomplished. His assessment by then is pretty sober.

The withdrawal itself would likely retrigger all his accumulated conflict and regret. It would be painfully personal. My hope would be (and this is me the author speaking, not the character) that ending the occupation of Afghanistan and having no more American troops on the ground might at least give Teddy the chance for closure. At least the war is now officially over.

Sahro has been through so much: the violent turmoil of her childhood in Somalia; the murder of her parents; the constant displacement; and her truly harrowing journey northward to Canada. She is a devout Muslim, and during her travels, it seems like she is sustained and centered by her daily prayers and ablutions. The regular prayers and rituals of Father Christopher at the monastery also seem to center and sustain him throughout his far more cloistered existence. Though their religions and circumstances are different, do you feel that these two characters share a sort of spiritual bond through their strong sense of faith?

I’m not sure it’s as much a spiritual bond they share as a daily practice and a belief system that sustains each one of them. As a practicing Muslim, Sahro prays five times a day, and as a Catholic monk, Christopher does the same, each of them at roughly the same hours. The names of their prayer times differ: Vigils, Lauds, Vespers, for example, or Fajr, Zuhur, Magrib; but they serve the same function.

At the monastery, Sahro notices the church bells ring at the same time as her azaan, her Call to Prayer, and this fact comforts her and connects her to Christopher and the other monks by an unseen thread. It’s a thread that runs throughout the novel, their parallel beliefs and shared biblical stories and prophets. I wanted to show the continuities between the two, actually three, religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—and show how each of their holy books, the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Qur’an, form a kind of trilogy that can act and should act more as bridge than a wall. Sahro understands this intuitively. So does Christopher. They have no argument with each other’s religion. They share the same faith which, in some sense, is faith itself.

Giovanni Bellini’s painting, St. Francis in the Desert, is of continuing significance for Father Christopher. The work is described with such intense detail in North, from Christopher’s first connection to it as a child, then when he sees it regularly while working as a museum guard, and later at a key moment in his spiritual conversion. Does the painting also have personal meaning for you?

It does. I first saw the Bellini painting at the Frick when I was a teen. It had an immediate hold on me. The mysterious robed man on the greenish rock, the ominous sky. The man’s expression and the tree. I didn’t even know who St. Francis was at the time. It didn’t matter. Something in the painting haunted me; it was both appealing and a little repulsive but I couldn’t help staring at it. Each time I went back to the Frick over the decades, as I grew older, I found myself still staring dumbstruck at the canvas, in the same way St. Francis, inside the painting, stares dumbstruck at the laurel tree.

When I started writing about Christopher Gathreaux’s relationship to the painting, I didn’t realize I was secretly explaining the painting to myself, putting into words what had been previously inexplicable and wordless. I had to take a deep dive into the painting and find out what it was doing and how it was doing it. By throwing words at the visual experience, by reasoning it out, I thought I might ruin that experience, but I was wrong. Knowing what Bellini was doing made me appreciate his painting even more.

Perspective is so essential and effective in North, as it alternates from Sahro, Teddy, and Father Christopher. Their perceptions of Vermont are varied, and we see many facets of the state through their eyes. Teddy is a native Vermonter, while Father Christopher has chosen it as a place to lead a contemplative life. Sahro, on the other hand, is traveling through a landscape totally different from her Somalian homeland. How is Vermont unique for each of them, and even from other states in New England?

One obvious reason Vermont is unique from its New England neighbors is its small size and its lack of any large city, its essential rural character. Vermont also has one of the whitest (if not the whitest) populations in the country. So while Vermonters, at least some of us, pride ourselves on our progressive politics and commitment to social justice, we rarely encounter, let alone live alongside, immigrants or people of color. So there’s this nagging contradiction, and sometimes disconnect, between sentiment and fact in the state. Our beliefs are rarely tested by reality.

In North, Vermont signifies in different ways to different characters. Teddy Fletcher’s Vermont is essentially the old conservative Anglo and French Canadian Vermont that is rural working class. Christopher, the monk, comes from elsewhere and like so many “flatlanders” before him, he can afford to romanticize and create his own Arcadia there. Sahro, for her part, has no context to judge Vermont. She notices only the beauty of the place, the darkness and silence, the mountains, the brilliant stars at night which remind her of the dark skies back home in rural Somalia. Because she’s been stuck in detention for so long and then awaiting her hearing inside a New York City apartment, she’s impressed by the quiet mountains and clean air, the new spring green. All of this is balm to her in her fugitive state.

Held in a detention center for eighteen months by one American presidential administration, then aggressively pursued for deportation by the next, Sahro ultimately seeks Canadian asylum. But she is entering Canada illegally, and her fate there is still uncertain. As a Somali refugee, does she have better options in Canada or could she end up in another maze of bureaucracy?

At the time when the book takes place, early 2017 right after Trump’s inauguration, a lot of undocumented immigrants were crossing the northern border into Canada. They were afraid of what was to come—the “Muslim ban” and the increased ICE raids and deportations. At the time a steady stream of migrants were heading to Canada through New York State and Vermont. Plattsburgh, New York, saw a lot of traffic as the last stop before the illegal border crossing at Roxham Road. When you entered Canada illegally there, the Royal Mounted Police would first arrest you and then assist you with your luggage to a processing center to claim asylum on the Canada side. You had a much better chance of finding asylum then in Canada. But then Canada started restricting the numbers of their asylees. I’m not sure where the numbers stand today in relationship to the United States. But back then, Sahro would at least have had a fighting chance as she’d be with family friends in Canada. Still, she had no guarantee of asylum in Canada as well. I wanted to make that clear at the end of the book, that her journey is not over, that she might never find a home.

At the end of North, Sahro, Father Christopher, and Teddy have reached a distinct point of connection, completion, and renewal. Do you see a continuation of their stories in another novel, or perhaps the flow of one particular character’s life becoming a separate work?

I see a continuation of their stories but not inside another novel. For the past few years I’ve been working alongside the Vermont office of the US Committee on Refugees and Immigrants with a number of Somali men and women who’ve resettled in Vermont. We’ve been helping these men and women tell their story in their own words, gathering what might be lost to the next generation—because asylum seekers often don’t want to look back at what they’ve been through, but forward towards the future. So far the work and their sharing of their stories have been so mutually gratifying. If there is any continuation or legacy of North, it will be with these people’s stories, their lived experiences put into words. It’s the continuation of a larger ongoing story of human displacement in a changing world, the ways we have of surviving. One of those ways is through telling stories.

Meg Nola