It looks like you've stumbled upon a page meant to be read by our code instead of viewed directly. You're probably looking for this page.

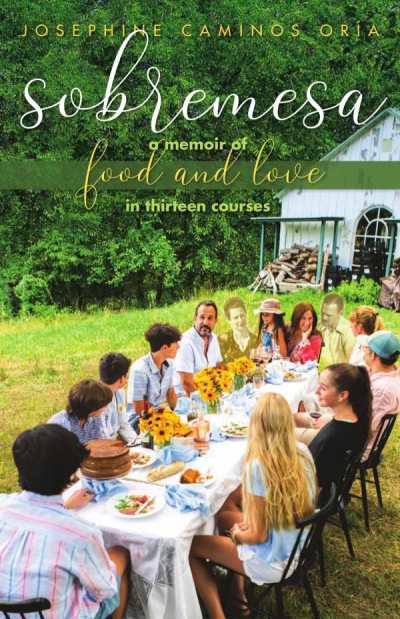

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Josephine Caminos Oria, Author of Sobremesa: A Memoir of Food and Love in Thirteen Courses—Part Two

Okay, ladies, top up your coffee cups and then let’s resume your conversation from last week. Josephine, we especially look forward to hearing about how your ancestors and spirit guides interact with you and influence your life.

For those of you just joining us, check out Kristine’s starred review of Sobremesa. Much thanks to Scribe Publishing for bringing this incredible story to light.

I loved the touch of magical realism in your book. Please share what it felt like to be visited, and, in a sense, guided and protected from beyond the grave.

Sobremesa’s celebration of the endless table and its ability to keep memories alive will hopefully attract readers who are drawn to the Latin American magical realism genre that poses the question: if food and drink sustain us in life, why not also in death?

My experience is that the dinner table and food itself acts as a portal to conjure to mind loved ones who are no longer with us—oftentimes through the mere act of taste and smell. In a small way, as long as we cook the food they made for us in life, we continue to keep them alive to share with generations to come.

Then there are the ancestors or legions of angels who guide us, yet we don’t quite understand who they are or why they have come. We even try to convince ourselves that they were merely a figment of our imagination. That’s how it was for me for so many years. Though I can’t quite understand why, I started becoming more aware of a certain guide after a terrible car accident I had at the age of sixteen. The few sightings I had left me feeling frightened at first, and then perplexed. It took years and years for me to understand why the Spirit I refer to as my “Gentleman Caller” was watching over me, but it gave me an incredible sense of hope, and served to fortify my faith in God and the beyond.

Some of my most memorable visitations have been in dreams—the most poignant one being when my abuelo Alfredo sat beside me on my bed, grabbed my hand, and told me that my heart was in the palm of his hands, and that it was time to go home, referring to Argentina. I was in my early twenties, at home in Pittsburgh nursing a broken heart at the time. But I can still feel Alfredo, even smell him, when I think back to that dream. And it fills my heart to know that, so many years after he left this world, he came back to help his granddaughter find hope again in the only way he could, by guiding me back to his home in Argentina. Now, maybe another person would have interpreted that dream as just a dream. But in my heart, I know he visited me twice that summer. I haven’t seen him since. Sometimes I try to manifest him as I’m falling asleep, but our Spirits and Guides choose to come to us when we most need them, or possibly when we are most open to them. I find that if I get too busy and do not ground myself with some sort of meditation, I close myself off to receiving their messages.

You mention having experienced other “mystical, faceless angel encounters,” and how your daughter, when she was two, ran into oncoming traffic and was saved by her guardian angel. In what other ways have you felt the presence of guides from the spiritual realm? Have they helped you avoid dangerous situations, or warned about making bad decisions?

More than anything, I have received signs—call it my intuition, my gut talking to me, possibly even God talking to me. I’m not sure what the source is, but there have been moments in my life that I just come into a “knowing”—for the good and the bad. I can’t quite tell you if this voice has helped me to avoid making mistakes, but it has helped guide me or influence a decision. The act of turning to writing, for instance, came to me from what I like to call “above.” I still cannot fully digest the Angel I saw appear when my daughter ran into traffic when she was two. I didn’t feel worthy of seeing her, or of the blessing she brought me. But then I realized that God reminds us we are all worthy and perfect in his eyes. And that when she saved my daughter, she saved my entire family. I have always felt my daughter was a gift from my mother, so it doesn’t shock me in the least that she has a Guardian Angel at the ready. It fills me with peace. It has been quite a while since I have felt a true presence from the other realm. Like love, or life itself, they seem to come when we least expect it. But I do believe we all have legions of ghosts and ancestors guiding us along, and I am so grateful for them.

How might those who’ve not grown up with the tradition of sobremesa but see its value begin to incorporate it into their lives?

Through the years, I’ve noticed that when guests come over for dinner, the women will mostly band together once the food is done and tackle the dirty plates and kitchen together as a team. It’s a sight to see, how efficient a group of women can be. And their intentions are nothing but good. They do not want their gracious hostess to awaken to a terribly dirty kitchen. But the simple act of sweeping away the plates disrupts the magic that could happen tableside. It makes people feel that they should be done and should possibly get up and help as well. Once people get up, the spell is broken. In past years, I’ve forbidden it and asked them to leave the dishes to the side. The dirty dishes and pans can wait, but this moment we have together cannot. Once we get up, it’s gone, over. When we look back at our lives, we will not remember how many evenings we went to bed with a tidy kitchen, but those unforgettable tableside moments stay with us for a lifetime. Our life is defined, even flavored, by moments. For someone who doesn’t tend to settle in at the table, I recommend they let the dirty dishes wait and ask those dining with them to stay seated for a while. Try it, maybe even just once a week. Possibly on weekends. Those little changes will have lasting results in many areas of your life. Sobremesa encourages people to stay—stay awhile at the table; stay receptive to conversations they might not otherwise have; stay open to feelings or ideas or possibilities they often can’t put words to.

With the polarization we’re seeing in the US having grown to the degree that it is tearing families apart, what is there in the sobremesa tradition that might help in dealing with disagreements?

The act of sobremesa encourages deep, honest, passionate conversation. I truly believe that introducing this tradition to those who still don’t know about it or quite understand it couldn’t be timelier.

Sobremesa gifts us the time we need to clear our minds and make sense of the immediate world around us—of our dreams and insecurities. It slows time down so the walls can crumble and let people in. It allows the time for our thoughts and fears to marinate until they get to where they need to be, to be digested and understood. And while that time at the table might be heated, if each person gives one another the time and space to speak their truth, then that lays the groundwork for mutual respect and understanding moving forward. After all, don’t we all long to be accepted for who we really are? At the end of it all, we should all be able to kiss and make up.

What do you feel is your book’s most important message?

I wrote Sobremesa for anyone who, like me, reads cookbooks like novels; for fans of armchair travel who’ve always dreamed of seeing and tasting their way through Argentina. With the exception of the choripan (chorizo in a bun, the perfect answer to street food), Argentina is not a grab-and-go sort of place. It is a magnet for people who, drawn to the slow food movement, want to experience its indigenous cuisine, the air, fire, smoke, hardwood, flames, coals, ash, salt, meat, bread, and wine that define gaucho-style cuisine and culture. But while the “eater-tainment” aspect of wood-fire cooking has successfully managed to put Argentina’s little-known cuisine on the map, the camaraderie and culture that sustain sobremesa remain lost in translation. I aim to change that and move the current in our collective cultural conversation about Latinos in the US forward by producing an intimate portrait of my bicultural Argentine family.

I hope my story will especially resonate with US born Hispanic millennials, who, like me and many second-generation ethnicities, have adopted many US and English customs but still appreciate, respect, and enjoy their culture, language, and heritage. But Sobremesa‘s bilingual language of cooking and eating isn’t intended for Latinos or Spaniards alone. It needs no subtitles and can and should be read cross-culturally as it not only celebrates our differences, but our likenesses as well.

While Sobremesa is my story, I hope a part of it is the readers’ too. Maybe they have their own abuela Dorita whose spirit comes alive in its pages, or, like me, they are bicultural, Argentine, possibly even from Pittsburgh; perhaps they’re in the midst of taking a chance on a second act (whether it be in love or professionally), or quite possibly they’re simply looking to take a seat at sobremesa’s endless table, where there’s always room for one more.

My other hope is that readers get lost within Sobremesa‘s pages. My intent was to write a culinary memoir that reads like a novel. The story itself is a gastronomic meditation on food itself. Because while we all need to eat, food is so much more than sustenance. It’s the feel of a place. It’s the essence of a person. It’s something language can’t get to. Its memories are tucked away deep inside all of us, reminding us who we are and who we are meant to be. I find courage and healing in other women’s journeys. I hope mine will help readers find the “brave” deep within themselves, or at least inspire them to roll up their sleeves and get back in the kitchen.

As a wife, and the mother of five children as well as an entrepreneur and writer, how do you manage it all?

I don’t manage it well. But I thrive in the crazy chaos and love for my family. Most days, at least. The sacrifices I have made in the last years by leaving a comfortable career have been great, but they have also allowed me to take back my time and earning potential on my terms. And that is priceless.

Like many, I too grew up drinking the Kool-Aid that told women it’s too late, or even selfish, to change the course of our lives after our mid-thirties, even if we intuitively felt something was missing. Once I finally came to understand that we have been fed this lie since youth—and had come to believe it ourselves—I decided to take a chance on myself. I left my fifteen-year, C-level career in healthcare to follow my passion and make dulce de leche—Argentina’s ubiquitous milk jam. At forty-three! Most of my friends and family thought I was crazy, myself included. Many offered their opinion: that I was too old to switch careers, that I would never make it. Many suggested I wait until my children were out of college to change things up. “How could I, the main breadwinner, put myself before my five children and husband?” they’d ask me. Looking back now, from the vantage point of years gone by, it’s hard to believe a single ingredient could have the power to divert the course of an entire life, to rewrite the hundreds upon thousands of decisions made—some on a whim, most carefully thought out—on which it was built. But that’s how it happened. It was greater than me, and there was nothing I could do to stop it.

I was tired of dreading Sunday evenings, facing a week like the one before. I knew it was up to me and only me to write my story. I finally decided that the idea of never trying was worse than failing. So, I decided to take a leap of faith and create something inherently ours—Argentine-American, with my husband, Gastón. I realize now, that I would be failing my children as a mom if the only thing I taught them was to play it safe for others. My hope is to teach by example and inspire my children, as well as other women who are questioning the path they find themselves on, to go against the grain and fight for a life worth living.

Please tell our readers something about your business, La Dorita Cooks, named for your grandmother.

La Dorita Cooks is the maker of the artisanal product line of La Dorita dulce de leche spreads, in addition to being Pittsburgh’s first commercial kitchen incubator that offers shared commercial kitchen space and business support programs for local start-up and early-stage food makers that aspire to become established, high-growth food enterprises.

Since opening our doors, La Dorita Cooks has helped new business owners access the resources and assistance they need to grow successful food companies. Today, La Dorita Cooks acts as a proxy to capital in early years when growth is risky. We aim to help businesses get profitable, prove concept, and show growth before having to raise the minimum six-figure amount required to get a licensable commercial kitchen. Located in the Borough of Sharpsburg, PA, a designated food desert in Allegheny County, our kitchen-share incubator program plays an important role in improving Pittsburgh’s underserved economies, creating jobs, and encouraging innovation.

Our business philosophy is simple: stay true to the food, stay true to family, and lend a helping hand where needed, just as our company’s namesake, my abuela Dorita, would have done.

Can we hope for another book? What might be its topic?

While Sobremesa is my second nonfiction, food-based book, I definitely do not intend for it to be my last! I have lots of ideas brewing. But one I’ve been thinking about more and more is to delve into the children’s food-fiction-fusion genre with a chapter-book series titled Dori Bori that will feature food-centric adventures loosely based on me as a child and my abuela Dorita. The series will have a bicultural feel and be interspersed with Spanish words, smidgeons of magical realism, and child-friendly recipes that will inspire children to get in the kitchen with their grandparents, parents, older siblings, or caretakers.

I’ve been hosting cooking classes for underprivileged children at La Dorita Cooks. With the series, I look forward to introducing children to the Argentine dishes my abuela taught me as a child in a fun and entertaining way that also allows them to get lost in the pages of a book.

Kristine Morris