Words for Elephant Man

- 2012 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, Poetry (Adult Nonfiction)

Sir Frederick Treves, the London Hospital surgeon who studied the Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick (1862-1890), wrote of him, “I supposed that Merrick was imbecile and had been imbecile from birth.” The conviction was no doubt encouraged by the hope that his intellect was the blank I imagined it to be. That he could appreciate his position was unthinkable.” Throughout this moving collection, poet Kenneth Sherman recreates Merrick’s voice, carrying readers deep into that unthinkable place where, in one instance of seeing himself in a mirror, “I stared and stared and then I / cried, / not just for me, / but for / the spectacle, / the story” (“In the Year of Our Lord 1875”).

Merrick’s short life story is told primarily through personal poems that allow readers to see the world through his eyes. In “The Show,” which depicts Merrick’s experience in a carnival freak show, a fascinating transformation happens in the crowd, making readers question who “the monster” really is. Waiting for Merrick to turn toward them, “their eyes / grow wide / swim out in circles / over the contours of my head … / They push / en masse / long neck of some straining beast.”

Throughout Words for Elephant Man, Sherman uses masterful imagery to help readers understand and internalize the feeling of having such deformities revealed to the world. The images surprise at every turn—for their originality, their accuracy, and for the way they pierce the emotions. His body is described as “a breathing tuber,” “a curdled question mark / that breathes,” and his head takes on the descriptors “gallon” and “elaborate.” In the opening poem, “A Psalm of the Elephant Man,” his mouth is “a shattered clam / a tortured vent” and we draw hints of the increasingly mechanized world of Merrick’s time with the description of his speech: “my consonants grind / and splutter / like an engine’s damaged / gears.”

That same poem ends with the line “I drone on in His image.” Often in the collection, Sherman uses religious imagery and has Merrick test the notions of “God made flesh” in poems such as “The Congregation.” In it, Merrick describes how the heads of those in the congregation “turn from the vacant cross / to catch a glimpse / of this body.” In the poem “Treves’ Description of Merrick,” Treves depicts Merrick’s face as “no more capable of / expression than a block of gnarled / wood.” And Merrick reacts to that notion with the line “What they nail me to.” Again, in the poem “Nurses,” he imagines what it must be like for the nurses to go home, knowing that they have “touched my sacred flesh.”

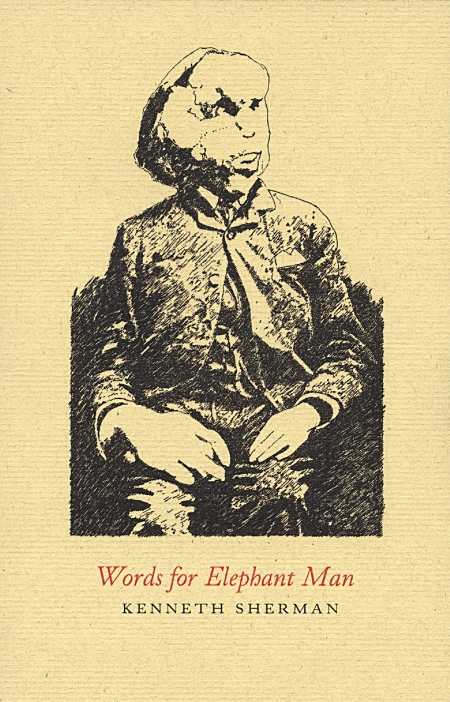

While the story of the Elephant Man may be familiar to many, Sherman’s poems take readers to the heart of understanding the intelligent, tender-hearted man who lived within his “bales of skin.” Containing etchings by George Raab, Words for Elephant Man moves beyond the reach of poetry readers, making it an essential book for anyone interested in Merrick’s life and times.

Reviewed by

Jennifer Fandel

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.