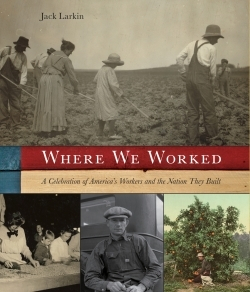

Where We Worked

A Celebration of American Workers and the Nation They Built

- 2010 INDIES Winner

- Honorable Mention, History (Adult Nonfiction)

The hundreds of men, women, and sadly, children staring back at the reader from the pages of Where We Worked have three things in common—they do not smile, their thin and stringy bodies evoke hard work and hard times (seventy-hour work weeks were the norm in nineteenth-century America), and all of their jobs—blacksmith, cobbler, hat maker, cowboy, even telephone operator—are now a thing of the past.

Museum scholar, author, and historian Jack Larkin has pulled together a rich collection of photographs, drawings, lithographs, newspaper cartoons, and advertisements, mostly from the Library of Congress, but also from labor unions, public libraries, and a few from his own family album, to create a picture of the hardest-working people in the history of the world.

And, as Larkin reminds us, it isn’t a pretty picture. Not only were work hours long, but the working conditions were unbelievably bad by today’s standards. Work was often so dangerous that disease and death were were taken for granted by the workers themselves. Painters and typesetters spent every day inhaling fumes of poisonous lead. The deadly fulminate of mercury used in making hats gave workers “the Danbury shakes,” so-called because Danbury, Connecticut, was the largest hat manufacturing town in America in the nineteenth century. The Chinese workers constructing the railroads were killed on the job with such frequency their plight gave rise to the phrase “Chinaman’s chance,” meaning no chance at all.

But Where We Worked is also a story of great innovation, ingenuity, and change. As Larkin points out, a farmer in 1620 Plymouth Colony would have been at home on an American farm 200 years later, because very little had changed. By 1840, however, that same farmer would have been lost. The locomotive, the cotton gin, Cyrus McCormick’s mower and thresher, even the sewing machine, would change the world of work forever. Every innovation in farming or manufacturing paradoxically caused massive unemployment. Some job skills lasted less than a lifetime. Even the venerated open-range cowboy, so much a part of literature and film today, found his heyday lasted only thirty years, from the end of the Civil War until the government shut down the open ranges in 1896.

This lively and down-to-earth book journeys from the dawn of the nineteenth century through the 1930s. It will especially appeal to the young adult reader who has never seen a dial telephone, much less a telegraph, textile mill, or blacksmith shop. It’s fascinating reading.

Reviewed by

Jack Shakely

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.