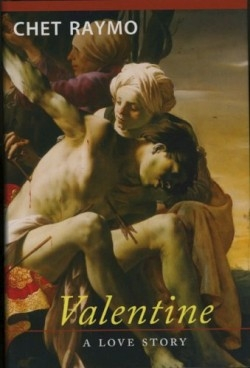

Valentine

A Love Story

The origins of Valentine’s Day are a curious and tangled mix of pagan holiday, Catholic martyrology, and romantic medieval lore. Even within the martyrologies, three Valentines exist. Who is the namesake of Chet Raymo’s sparkling third novel Valentine: a Love Story? This Valentine is born partly of one martyr story about a third century Roman doctor, and partly of the legend of a saint who fell in love with his jailor’s daughter.

Valentine begins life an irresponsible teen, becomes a respected Roman doctor, and dies at thirty-two, “lashed to a post outside the Flaminian Gate of the city and shot dead with arrows.” But to this common narrative, Raymo adds surprising twists: for one, that Valentine is an accidental martyr, a thinker whose real crime is a certain anti-Romanness about him. Valentine doesn’t see a gladiator game until eight years after he’d moved to Rome, and when he does, he vomits. And while Valentine doesn’t die for faith exactly, his original, intractable stance on “superstition” is, at the very least, softened by his love for a Christian woman.

This summary gives nothing away that isn’t revealed in the first ten pages of the book. For the point isn’t Valentine’s death, or the particulars of it. This is a cautionary tale for our own intolerant, violent times. But what can we do against the tide of history, personal and monumental? Live decently, honestly, lovingly, intelligently. As Julius Marius Favus the jailor says, “Valentine died for love, yes…for my darling Julia. And for philosophy. Like Lucretius, he had sought to undeceive his own thought, to scrape through the encrustation of myth…”

The potential distraction in this engrossing tale is the disjuncture between Valentine the thinker and Valentine the lover. As a thinker, he seems to suffer an incomplete understanding of the rationalist philosophy he adheres to, substituting love of ideas for love of life. In youth he runs away from his birthplace because he has impregnated a girl; in manhood, he loathes the gladiator games more because he loathes “public excess” and his own sexual stirrings in the presence of violence than because that violence exists.

So when Favus claims that in Julia “Valentine saw…the innocence that he had lost, the idealism that he had foolishly squandered for wealth and social status,” one may ask, “What innocence? What idealism?” Valentine seems to morph rather instantly into a different person, but great pains are taken to provide continuity, to false effect.

It is a small point, one misstep in an original and deeply affecting work. Soon the narrative veers off into the heartbreakingly operatic sweep of its last third, and we are reminded that while myth always has purchase, it has little meaning without love.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.