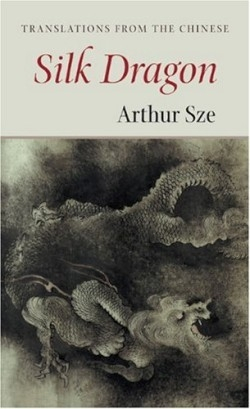

The Silk Dragon

Translations from the Chinese

These delicate poems, charged with a sense of serenity that seems incredible to modern sensibilities, cast images of an almost mythic world—formal and austere, yet infused with the banked passion of “red pomegranate wine.” Chinese-American poet Sze advises in his introduction that he has shared all the translations that he’s satisfied with in this collection of fifty-three poems by eighteen Chinese poets, ranging from T’ao Ch’ien (365-427) to Yen Chen, still writing in China.

The book’s title springs from an image in one of its poems, by Li Shang-yin (813-858): “A spring silkworm spins silk / up to the instant of death.” Taking this as a metaphor for how a poet works with language, and adding the idea of the dragon as magical and transformative, Sze arrives at “the silk dragon” as his own personal metaphor for poetry.

“Spring View,” by Tu Fu (712-720), describes the ability of the ancient Chinese to find repose and acceptance in the midst of war, famine, and plague. It begins with “The nation is broken, but hills and rivers remain…” and ends: “The beacon fires burned for three consecutive months. / A letter from home would be worth ten thousand pieces of gold. / As I scratch my white head, the hairs become fewer: / so scarce that I try in vain to fasten them with a pin.”

One of the impressive things about Sze’s translations is the extent to which he pays attention not only to the intellect invested in any particular poem, but its emotional tone. His illustrated exegesis on the intricacies of Chinese pictographs and his poetic sensibility toward the original works are persuasive because of their intelligence and his humility. His approach to the problem of translating from a pictographic language to an orthographic one is charted in an introduction that could be a lesson for every aspiring translator. Notes on both the poets and their works serve to make the poems more accessible and the poets less exotically strange.

Bilingual all his life, Sze studied with a series of accomplished Chinese poets, critics, and scholars. Author of six books of poetry, he has received a number of prestigious awards; appropriately for one who understands the joys and problems of bilinguality, he teaches Creative Writing at the Institute of American Indian Arts in New Mexico.

Reviewed by

Sandy McKinney

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.