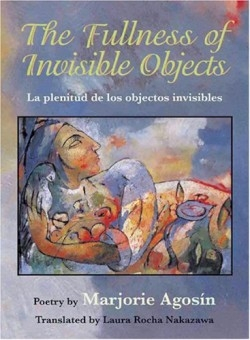

The Fullness of Invisible Objects

After decades of lament and outrage over the atrocities that drove her family out of their native Chile, Agosín, nearing age fifty, has mellowed into a serene, though certainly not placid, desire to recover the half-wild, half-innocent wonder of childhood. One outstanding quality of the poems in this collection that makes any one chosen at random recognizably Agosín’s is their delicacy. It’s possible for a close reading to cover twenty lines without encountering an adjective, weaving a texture so fine it could be a place mat for a picnic in the air.

Air is what it’s about, the essence harboring those invisible things air conceals and preserves: the memory of footsteps; the pervasive echo of a voice forgotten for years and recovered in a moment of listening to birdsong; the yearning of a hand to touch with love, with the thrill of exploration, a beloved face; to listen, with every note, to new words from an old beloved voice; the spectacle of a scene from nature seen for the hundredth time in a new light that presents it entirely recreated. In her introduction, the poet speaks from her heart: “I wanted to celebrate life in its smallest, sonorous rhythms; I wanted to see the world with the same astonishment that I felt as a child when I used to count the stars.”

The realization of this aspiration comes with lines like, “The cycles of incantations / allow you to return / and you are dressed in sun and water.” “You decide to confess your love, / writing long love letters to your dead grandmothers / thanking them for their steps that never / watched you but knew how to wait and / listen like someone who returns from the highest treetop / resting upon dreams and sings.”

Many of these poems seem to be addressed to an unspecified “you.” In them, Agosín celebrates in a new voice feelings, memories, desires, those cherished things opposite everything she has spent half a lifetime railing against. It is as though she has finally acknowledged a lover who has been hiding in the wings for decades. The acknowledgement is tentative, cautious but experimental until the joy of touching reaches a radiance almost, but not quite sexual, with a tenderness more maternal than erotic.

Marjorie Agosín, a Professor of Spanish at Wellesley College teaches courses in Spanish language and Latin American literature. She has been a member of the faculty since 1982, and has received numerous awards for her contribution to the promotion of Hispanic and Latin American topics in the United States, including the Gabriela Mistral Medal of Honor.

Reviewed by

Sandy McKinney

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.