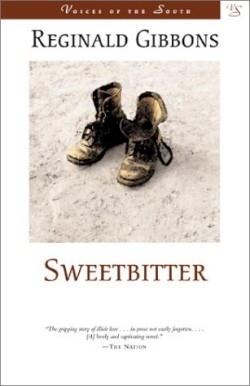

Sweetbitter

“Because she was as white-skinned as the moon and he was something akin to the color of red clay,” Martha Clarke plays a role as archetypal as Medea, or Ophelia. Her obsession with Reuben Sweetbitter, a half-Choctaw drifter, is met with an equal compulsion that grips them beyond sense, as defiant of taboos as a fatal disease.

A new title for LSU’s “Voices of the South” collection, this novel opens in 1910 in Three Rivers, Texas. Reuben is accepted with a certain self-protective reluctance by the Black community, but is spurned by the whites. Martha, from her first glance in his direction, becomes a pariah even in her own family. The author pursues his characters with a Faulknerian sense of doom and a prose so lyrical it skirts the edges of poetry, as they live out their bewildering Karma of passion, prejudice, and peril-as innocent of will as a couple of refrigerator magnets.

The recipient of numerous prizes, Gibbons was granted for Sweetbitter the coveted Anisfield-Wolf Book Award reserved for sparsely chosen books dealing with racism and cultural diversity. Although he is a professor of English at Northwestern University, and was for some years editor of Northwestern’s literary magazine, Triquarterly, Gibbons clearly derives this novel’s voice from its Texas setting, in his rendition of both the landscape and the speech patterns: “Yore goddamn lil half-breed girl’s shadduh is touchin my boy. Now stand off, nigger. … Git down the street with the rest of the niggers and take your whore of a wife with you.”

The scenes are drawn as casually, and as naturally, as a drop of moisture slides down the outside of an iced-tea glass on a sultry July afternoon in Texas, until the unspeakable insults hurled at the intrepid couple almost lose their edge. The final chapter is a pure rhapsody of possibilities for the fleeing Sweetbitter, who has been discovered and accosted by Martha’s brutal brother. Martha, who has settled for semi-respectability in a town miles away from the original scene of her scandalous liaison, will no doubt find solace with her children and her matronly protector.

Reuben is not so fortunate, but the possibilities offered for his eventual freedom bring the story to a heroic close: “He’d run and run. Past the trees that were watching him and unable either to aid or harm him. Past an old snakeskin sparkling fantastically with crystals of snow along its dry contorted length. Past weeds nodding their heads under caps of white.” His voice precedes his flight: “Ya kut unta le ma / oboyo ut akiania / yo me kia ne ne / isa kanimi” and leaves the reader cheering for his release from the stultifying life of pretense and self-denial that has been the payment for his fate-driven love.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.