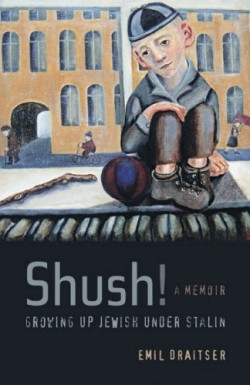

Shush!

Growing Up Jewish Under Stalin

In the long trail of tears that constitutes Jewish history, one bright spot is the triumphant rescue of Russian Jewry. Although supposedly no official anti-Semitism existed in the Soviet Union, there was in fact considerable repression, especially directed toward those Jews known as “refuseniks” who sought to emigrate. Jews around the world rallied to their cause and diplomatic pressure was exerted. Eventually, one million of them were permitted to go to Israel and about 500,000 left for the United States, Germany, Canada, and other countries.

The hardships experienced by Soviet Jews are poignantly described in this memoir by Emil Draitser, who managed to reach America where he is now a professor of Russian in New York. Born in Russia in 1937, he concentrates in the book on his life until 1953, when Stalin died and the Jewish doctors accused of being poisoners were declared innocent. Draitser joined the celebration, albeit somewhat hesitatingly since he had systematically tried to identify himself as a Russian rather than as a Jew.

Beginning with his first day at school, his efforts to downplay his identity failed since his classmates and his teacher taunted him as a Jew. He joined Communist youth movements and saw himself as a “citizen of the USSR,” but continued to encounter anti-Semitism. At home, he was somewhat puzzled when his parents quietly observed Jewish holidays. His father taught him to root for Jews in the world chess championship, to take pride in the few Jewish winners of the annual Stalin Prize, and to know that both Marx and Einstein were Jews.

Confusion was intensified for Draitser when he was taught in school that Russians invented the steam engine, the light bulb, the radio, the telegraph, the airplane, and the computer. The truth about the Holocaust was kept from him. More mixed messages came when he found anti-Semitic comments in the writings of his favorite Russian authors.

Fortunately for Draitser, he was able to come to the U.S. and learn how he had been victimized by Soviet propaganda. His narrative eloquently testifies to the persistence of Russian Jews in maintaining their identity as well as to the value of the protest movement on their behalf. This is a significant contribution to the understanding of life in the Soviet Union and to the vital importance of speaking out against oppression.

Reviewed by

Morton I. Teicher

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.