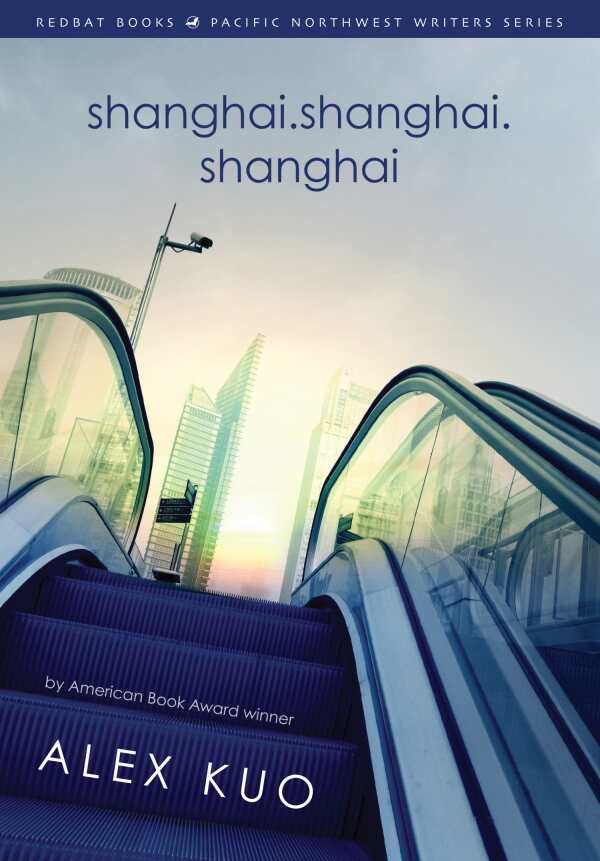

shanghai.shanghai.shanghai

Reminiscent of stream-of-conscience writing, shanghai.shanghai.shanghai is intensely rewarding reading.

Alex Kuo’s shanghai.shanghai.shanghai starts out straight forwardly enough. Ge is an arts writer for an English-language newspaper and a struggling author on the side with a successful restaurateur girlfriend. But the story immediately metamorphoses into something unusual when the text begins fluctuating between various years and various events in recent Chinese—and sometimes American—history. Reminiscent of stream-of-conscience writing, it can be difficult to follow, but also intensely rewarding.

To assist the reader, a typeface key is provided in the back of the book indicating who exactly the narrator of the text is at any given moment. For example, Ge’s interior monologue is orange (Kingthings Trypewriter 2), his published writings are in green (Lucida Grande), and additional proffered information—usually historical in context—is presented in sidebars of purple (Arial Narrow.) The author even inserts himself into the story via “author intrusions” in blue (Century Gothic).

While the current year appears to be 2014, Ge is also writing in—and the story is perhaps occurring in—1939, 1989, and 2008. Those years align with some tumultuous recent events in China: the Japanese occupation, the student demonstration in Tiananmen Square, and the Beijing Olympics.

Memorable characters, both real and fictional—such as “the blind, self-taught barefoot lawyer” who became internationally known several years ago and a pickpocket from South America nicknamed Bogota Man—are intertwined in time and even occupy the same space occasionally. A variety of seemingly random topics—the subject of war, the Peking Man, the 2007 world bridge championship—all collide and are part of the unfolding story swirling around Ge.

Definitions for several Chinese words are provided: for example, “he was a despotic ruler—a baojun zhuanzhi zhuyi—running a fascist secret service.”

One-liners pop up and tickle the funny bone, such as this bon mot about seeing a movie in the theater: “I didn’t like the movie; but then I saw it under adverse conditions—in the dark.”

Kuo, a retired professor of English at Washington State University, is the author of twelve previous works. He has also held several teaching fellowships in China.

Reviewed by

Robin Farrell Edmunds

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.