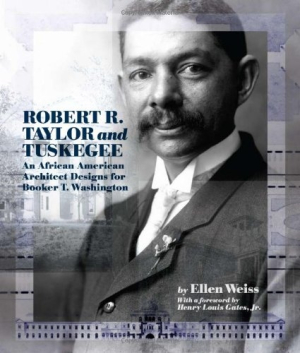

Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee

An African American Architect Designs for Booker T. Washington

As the architect of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute from 1892 to 1932, Robert Taylor, the nation’s first professionally educated African American architect, was charged with realizing buildings that would lend a unifying presence to the uneven terrain of the Alabama campus. His days involved building maintenance and teaching students various building trades, and at night he worked on his architectural designs. However, there was a taller order with which Taylor was also entrusted. The young MIT graduate’s superior talent and unflagging efforts at Tuskegee were intended to promote the dream of racial equality espoused by its founder, Booker T. Washington. Unsurprisingly, elevating the mindset of the institute’s mostly rural African American

students proved to be more rewarding than renovating the pervasive attitudes of bigotry

in the Jim Crow South.

At Tuskegee, Robert Taylor didn’t advance an African American style of architecture (there is no such thing); he designed buildings with a fitness to their purpose, exemplars of taste and civic responsibility that would promote Washington’s goal of constructing the broad economic base from which an African American middle class might grow. In the words of Ellen Weiss, Professor Emerita at Tulane University’s School of Architecture, “Taylor’s Tuskegee models a humanely scaled, visually rich world where impecunious and neglected youth might feel at one with themselves and perhaps with the larger world. The campus would help nurture black people into a higher and happier state of being and, not incidentally, force white outsiders to accept its parity with their own.”

The Tuskegee campus—with classical brick buildings, including dormitories and classrooms, a library, veterinary hospital, and chapel (Taylor’s favorite)—was impressive in its appearance and function: contemporary newspaper accounts carried praise from both reformers and skeptics, and white philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, president of Sears Roebuck, commissioned Taylor to design schools based on what he saw there.

The Institute’s students (including writer Ralph Ellison) learned their professional skills from Taylor and his colleagues through planning and constructing its buildings. The education preparing them to represent their race as dignified, competent professionals even extended to the proper use of utensils in the dining rooms. Weiss calls Washington an aesthetic activist, saying, “To [him], beauty was as essential as morality and work. All together would lead the race to a higher civilization.”

In scholarly yet accessible prose, and with the aid of vivid period photographs and architectural drawings, Ellen Weiss recalls a modest, likeable man in Taylor. Born to parents of mixed race in Wilmington, North Carolina, his father, a former slave, became the area’s wealthiest black landowner. During Taylor’s childhood both black and white families lived on their block in racial harmony.

Taylor did not leave behind many writings, but one article, “Where Are Our Architects?” holds continued significance. In it, he laments the dearth of African American designers, a condition that persists today. Washington ultimately believed that finances were the basis of true equality and that blacks were handicapped by undercapitalization. He encouraged them to invest in black-owned banks, which could then make loans to black-owned businesses.

Robert Robinson Taylor’s elegant buildings at Tuskegee didn’t shout; like the man, they led by example—and his descendants, among others, certainly got the message. The book’s foreword, by professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., reveals that Valerie Jarrett, a senior advisor to President Obama, is Taylor’s great-granddaughter. Scholars of architecture as well as of American history, specifically race relations, will find much to occupy their interest in this important book.

Reviewed by

Julie Eakin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.