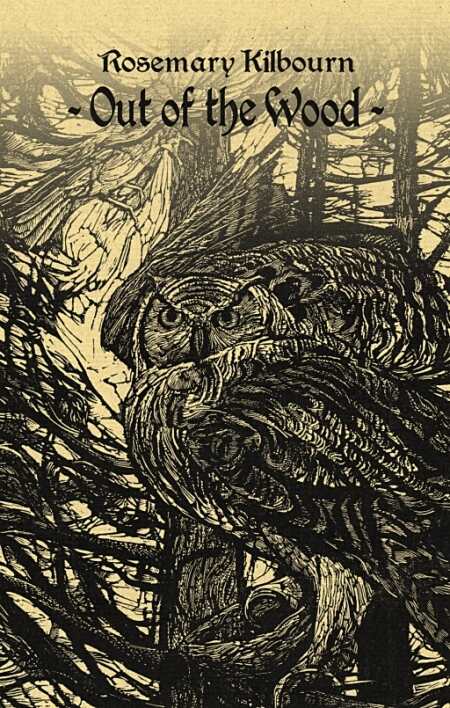

Out of the Wood

More than eighty prints executed over fifty years (from 1956 through 2006) tell the story of engraver Rosemary Kilbourn’s fascination with, and reverence for, both the practice of looking closely and the natural world that mostly occupies her attention.

“The land has an intelligence of its own that Kilbourn acknowledges through the gaze of a mind finely tuned to expressing its vitality,” says Tom Smart in his eloquent introduction to Out of the Wood. But hers is not the disembodied gaze of a distant observer: Kilbourn is of her surroundings. Continues Smart, “Her compositions insist that we belong to the landscape as surely as the trees and structures that blend into its topography.”

This theme of an integrated world resonates throughout many aspects of the work presented. And in the same way that Kilbourn’s glorious art cannot be separated from her rural Canadian lifestyle (which frequently forms its subject matter), so, too, does her book transgress genres—art, memoir, environmental study—as surely as it satisfies the criteria for each.

Some of the finest examples of the prints collected here form a group of six engravings detailing industrial scenes to accompany a book by her brother William, The Elements Combined: A History of the Steel Company of Canada. In them, we watch men working at a blast furnace, and we also see the farm equipment eventually made possible by their work. Whether Kilbourn’s subjects are industrial, biblical, such as the wonderful Obedience of Noah, or closer to home, like the many views of the former schoolhouse she so gratefully inhabits, the compositions are packed tight, with something of interest in every space on which the eye can rest and register its regard.

Throughout the book, the artist educates her reader using images and words. Kilbourn’s notes, opposite each print, discuss everything from her motivations to her tools and methods, forming an atypically friendly instruction manual. She writes with a graceful, straightforward style, as evidenced in this example taken from the preface: “Eventually I came to realize that some of the elements I most wanted to express in landscape were, to an extent, presupposed in engraving. The first was light. Brilliance comes from the contrast of the rich black printed from the surface of the block, while every cut into the wood I rendered as white. The process is not unlike drawing with light.” Considering that comment and the multiple framing devices inherent in her compositions, it makes sense that Kilbourn has added designing stained glass to her repertoire over the past few years.

Kilbourn’s sumptuous visions remind me of a fellow nature worshiper with an equally textured style: early nineteenth-century British Romantic painter Samuel Palmer. In the work of both artists, there is a kind of quiet ecstasy expressed that makes them a pleasure to behold again and again.

Reviewed by

Julie Eakin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.