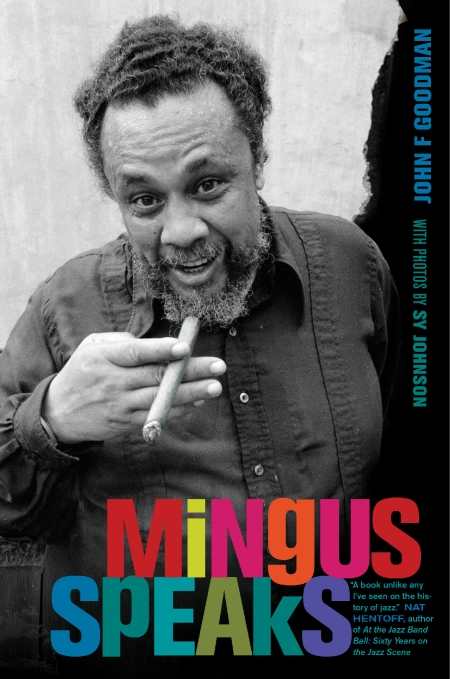

Mingus Speaks

From mercurial to mentally unstable, interviews highlight legendary composer’s Vesuvian stream-of-consciousness conversation.

James Joyce’s mastery of the written word might have an equal in Charles Mingus’s skill with conversation.

Charles Mingus? The legendary jazz bassist and composer? You bet, and in former Playboy music critic John F. Goodman’s penetrating biography, you’ll meet a consummate musician who loved to talk and could be in turn erudite, street sassy, and cruel. Mingus called this “spontaneous composition” in his music; it was the same in his words.

Mingus Speaks covers interviews by Goodman, in the years 1972 to 1974, with Mingus and some of his fellow musicians and associates. Mingus was at the very top of his game musically, but beginning to notice and fear the shadows of an illness that would kill him only five years later.

Goodman crafts the many interviews so that readers are initially introduced to the encyclopedic mind of Mingus, whose knowledge of music and musicians was outstanding. His Vesuvian stream-of-consciousness conversation was part hipster, part genius, and, occasionally, off-putting. He would weave Charlie Parker, the cellist Janos Starker, and generous dollops of the N-word in the same sentence. It can be shocking, which was Mingus’s intent.

Goodman moves us from the musical genius to a man whose praise could be high, but whose distaste for a whole host of musicians (Ornette Coleman, Bob Dylan, the Beatles) could be withering. Each chapter moves us further from the music and into uncharted waters, such as the Watts riots (which Mingus thought had been faked), the Mafia taking over the music business, and, finally, suspicions and perceived betrayals by those who worked beside him.

Goodman never comes right out and says it, but it is clear that Mingus was moving from mercurial to mentally unstable. He could be a teddy bear and a viper, sometimes within minutes. In the words of his long-time lover, Sue Graham, “He will infuriate people, humiliate them, insult them, beg them, love them, hate them … he gets musicians playing at the top of their ability, sometimes out of sheer fury, or of love.” It is almost incomprehensible to think that the man making such intricate and beautiful improvisations on “Let My Children Hear Music” is the same man holding a knife to the chest of Village Vanguard founder Max Gordon, but it’s true, and it makes for fascinating reading.

Reviewed by

Jack Shakely

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.