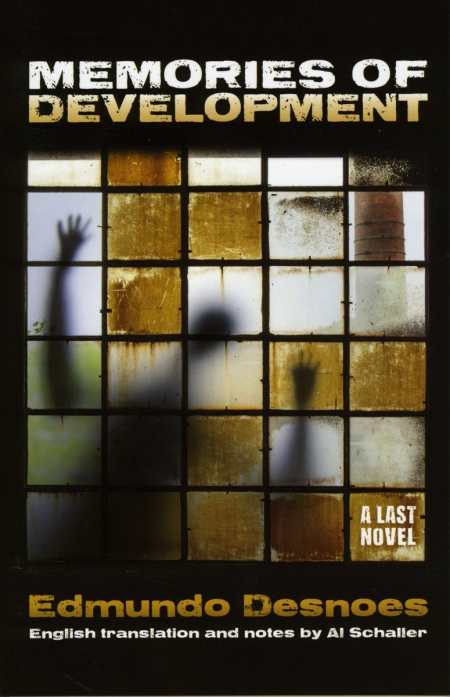

Memories of Development

A Last Novel

Anguishing in old age, this vivid character documents his fragmented memory of a childhood in Cuba and an art career in rural America.

“I know that memories wrinkle and spoil even more than the flesh—and I know they lie.” So launches Edmundo Desnoes’s Memories of Development, the sequel to his well-received work, a semi-autobiographical novel first published in Cuba in 1965.

Desnoes resurrects his character Edmundo and has him record his anguished final year in a diary. Although called “a last novel,” it is likely to have the last laugh as the reader searches for a coherent story to be told. Instead, what we get is an interminable rant full of self-admitted “tedious, pretentious pages” of an old man’s confrontation of old age and physical ruin: “I can’t help it; I frequently exaggerate my feelings even to absurdity. I deliberately let myself be transported into caricature; into grotesque exaggeration when I record what happens to me—but now the opposite has occurred. I can’t control my discourse; my narration controls and confounds me.”

Edmundo is caught between two worlds—the sweaty tropics of Cuba with its failed revolution and the moralized landscape of the northeastern United States with its crass materialism. He retreats to a cabin in the Catskills, but he’s like a bird pecking at its own image in the glass: “He sees the reproduction of himself, and he attacks. He sets upon his own reflection.”

Having abruptly left his tenured job as a professor of Latin American Studies at Smith, he embarks on a project to paint the female body, first in New York City and then starting over in rural America. In probably the best section of the novel, he gets involved with a Jehovah’s Witness from Montana.

Despite the disjointed narrative and bombastic style, Desnoes winningly evokes his childhood in Cuba, adding poignancy. There are images of men and boys diving for coins in Havana Bay around a steamship, his parents’ fraught marriage, and his brother’s fleeing before being denounced as a homosexual. But as the author laments, in an effort “to delve into my fetid memory, I only retrieve vivid details … fragments of experience.” It’s a pity that along the way, he decides “to leave in any repetition, to tolerate all redundancy.”

When he’s not wallowing in the abundance of exile or reaching for the erotic, Edmundo uses a diary so that he can remember and imagine who he is.

Reviewed by

Trina Carter

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.