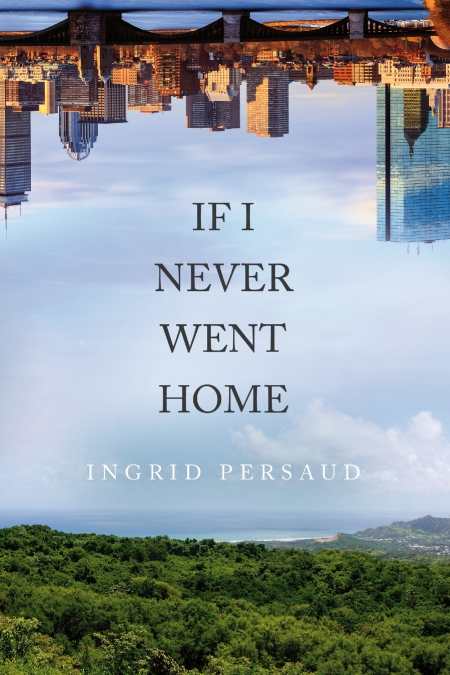

If I Never Went Home

- 2013 INDIES Winner

- Honorable Mention, Multicultural (Adult Fiction)

Powerful characters, evocative descriptions, and a tale of two cultures make this lyrical debut novel sing.

The old adage that one can never go home again rings true in Ingrid Persaud’s powerful debut novel, If I Never Went Home. The author, who divides her time between England and Barbados, places her protagonists, Bea Clark and Tina Ramlogan, in a similar position of straddling two cultures.

Having moved to America to attend college after spending her childhood in Trinidad, twenty-nine-year-old crisis worker Bea spirals into depression as she struggles with painful memories. Meanwhile, in Trinidad, rebellious Tina has to adjust to a different familial culture when she goes to live with her strict grandmother after her mother dies, all the while never knowing her father’s identity. Themes of belonging, familial relations, mental illness, and the meaning of home flesh out this leisurely lyrical novel.

Using the third person for chapters from Bea’s viewpoint and the first person for Tina’s chapters, the book draws readers into each protagonist’s vivid character, slowly revealing the link between the pair. Persaud deftly uses language to differentiate Bay Stater Bea from island girl Tina. As an educated professor, Bea speaks standard English, whereas Tina narrates in a Trinidad dialect that clips off “s” possessives, leaves out words, and uses pronouns in a nonstandard way. Tina says of her grandmother, “No sir, she not spending she little pension on no Carnival … ticket.” While Tina’s manner of speech can confuse at first, the language lends authenticity.

Genuineness also flows from Persaud’s brilliant turns of phrase. Bea has “a life tightly wound, with little give to stretch and bend,” in which “[a]nger, fear, and nostalgia would have to wrestle a final decision out of her.” The author particularly excels at creating empathy for her characters’ suffering by offering Bea’s tongue-in-cheek observations about the mental ward, in which she stays while depressed, and Tina’s repeated expressions of longing to know who her father. While Bea may describe her depressed self “like a brown-skin rag doll,” and Tina is a “Trini,” (slang for a native of Trinidad), Persaud manages to make their story simultaneously specific and universal, while allowing uninitiated readers to learn something about Trinidad’s culture.

That it takes so long for the protagonists’ paths to cross is both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, the desire to know their link keeps readers engrossed in the book. On the other hand, the connection occurs too late in the narrative. As a result, the ending feels forced and truncated when compared with the well-developed body of the novel. Also, the story often jumps from past to present and back again without adequately distinguishing in which time a scene is set. Powerful characters and evocative description make such things appear minor, however, and one hopes Persaud pens another novel for readers to come home to.

Reviewed by

Jill Allen

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.