Half in Shade

Family, Photography, and Fate

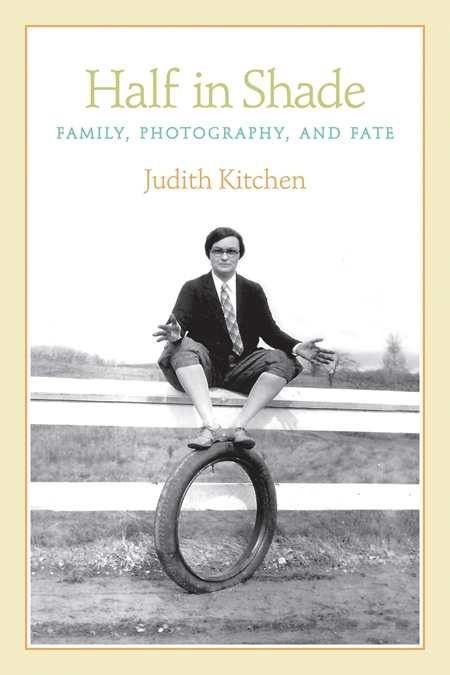

Judith Kitchen’s new memoir, Half in Shade: Family, Photography, and Fate, kicks off with the following disclaimer: “I have never owned a camera and I never snap photos, except reluctantly when asked by others.” It’s an odd way to begin a book about old photographs; however, this authorial distance—established from the get-go—renders Kitchen’s essays that much more powerful. The fact that she doesn’t particularly care for photographs invites readers to take a closer look at the ones she has included if only because this author has found in these images something worth seeing.

Half in Shade isn’t your standard memoir, but rather a curated presentation of old family photographs and stories—both real and imagined. A collection of essays strung together loosely (if at all), it’s a challenging read that captures in words the disorientation of flipping through images and the uneasiness of confronting the histories and hopes of people one will never know. While the distinctive organizational structure, with its zigzags through time, may not appeal to all readers, the subject matter is broad—encompassing everything from mother-daughter relationships to Europe between the wars to cancer—and the book as a whole explores themes of displacement, remembrance, and nostalgia, all of which are universal.

The driving force behind the memoir is the notion that, “The dead lose jurisdiction over their meanings.” What Kitchen plays with to great effect throughout the narrative is the idea of how we, the living, are meant to approach photographs in light of that knowledge. “A photograph sparks reverie and speculation. No two viewers will see it the exact same way,” she writes, before delving into the different ways a photo can be “read.”

One means of viewing a photograph is by letting, to quote Stuart Dybek, “What had happened … loom with the mystery of what will happen.” It’s an issue Kitchen confronts frequently throughout her narrative. She writes, “If it could be said that we measure time in wars—‘Civil,’ ‘World,’ ‘Vietnam’—then we bring to any photograph the shadow of ‘before’ or ‘after’: Paris, 1938; Chicago, 1912; Edinburgh, 1964.” Confronted with an image from the past, she allows, we are inclined to superimpose on to it what we know of the future. Considering a picture of her Aunt Margaret as a school child, Kitchen sees: “Already it is growing in her—the life she has yet to lead, and the death she has yet to face.”

On the other hand, the viewer also confronts a barrage of conjecture, the temptation to fill in a host of unknowns. As Kitchen writes: “What were their real lives? All the maybes hurl themselves at me.” The “maybes” are particularly striking in the case of photographs of Kitchen’s mother. “My mother’s life, as most lives do, fell into a series of choices,” she writes, “leading inevitably to her marriage, and then eventually to me.” Early in the book, a maternal push/pull emerges, wherein Kitchen (the daughter) is tempted to reimagine her mother’s life based upon the photos and diaries she has found, and take the narrative reins: “No, this is my story, the tale of how one day I tried to give my mother the romance I felt she hungered for. Posthumous romance, as though I could make up a life and hand it to her, and that alone would alter the direction of my own.”

Half in Shade is a serious book, but it’s leavened throughout with unexpected humor, particularly in regard to the establishment of time and place. Recounting the stages of adolescent romantic physicality, Kitchen evokes the fear of teenage pregnancy with the precise note of pathos: “Those were pre-pill, pre-abortion days, so you lived with the sense that you, too, could have to spend a year ‘living with your aunt in East Aurora.’” While the world that emerges in the memoir is, as the title implies, only half-illuminated, it’s nonetheless haunting.

Half in Shade is one of those rare, hypnotically enjoyable books that can be stretched out over many long, lazy afternoons or read in one sitting. Kitchen writes of photographs that “there is a mystery in the still moment. The very black-and-white of it. It serves as entry into another time, another place.” The same could be said of her words.

Reviewed by

Oline Eaton

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.