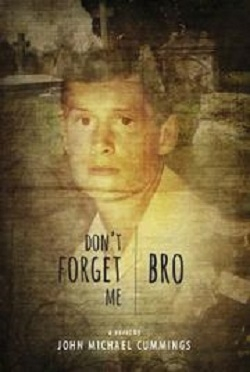

Don't Forget Me, Bro

The weighty themes of mental illness and abuse are skillfully balanced with a road trip plot line and observations on America’s homogenization.

In YA writer John Michael Cummings’s first adult novel, Don’t Forget Me, Bro, a middle-aged man returns to his small town after a decade to face family legacies of abuse and mental illness. The story stands out for its memorable first-person narration and suburban wasteland setting.

Mark Barr is a struggling New York City writer. He has not been in Alma, West Virginia, for eleven years, but when his brother Steve dies of a heart attack, he finally returns to the family home. Deploring the countryside’s decline, Mark revisits places where his schizophrenic brother was treated and discovers Steve’s unexpected depths.

Cummings has crafted a strong narrative voice. Mark perhaps shares this West Virginia author’s ambivalence about “visits” home: “Visiting was something I did with my dentist. In West Virginia, there were only reckonings.” Mark is sarcastic yet inventive in his language; he frequently comes out with snappy retorts: “What, so I know Dostoevsky better than dipsticks. That means something’s wrong with me?”

The novel benefits from solid supporting characters, including Steve’s mentally disabled friend, Sherry, and Whitey, an ex-convict who updates Mark on his brother’s recent voluntarism and church ministry. The Barr patriarch is among the most striking characters, even if descriptions suggest a clichéd villain: “If I cut my father open, I’d find a bullwhip coiled up where his heart should be.” It would be tempting to dismiss these West Virginia folk as “a bunch of dysfunctional hillbillies,” but Cummings renders them three-dimensional.

Flashbacks to Mark’s past are sometimes irrelevant, and the author occasionally resorts to tedious inventories of house contents. Fortunately, weighty themes of mental illness and physical abuse are not depressing, thanks to the fairly light road-trip format. There is even a gentle mystery element to “the quest to put Steve together like a jigsaw puzzle” and the quarrel over his remains. Yet Cummings also includes serious commentary on the country’s homogenization; passing chain stores, Mark thinks, “I could be anywhere in America.” He poetically laments a lost natural landscape: “Whole hills had been leveled, along with farms. Snaky roads replaced by wide blasts of macadam.”

This family-sensitive portrayal of mental illness should resonate with fans of Nathan Filer’s Where the Moon Isn’t.

Reviewed by

Rebecca Foster

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.