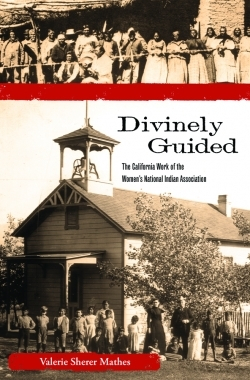

Divinely Guided

The California Work of the Women's National Indian Association

In 1879 the WNIA was formed in Philadelphia with the goal of helping Native American women. The altruism was sincere, but sometimes came with strings attached; the Women’s National Indian Association was an evangelical Christian group, and much of its idea of “help” was tied to both religious conversion and cultural assimilation. While those goals largely failed, the group did build several homes, schools, and chapels, and sponsored teachers and physicians for some seventy years. Divinely Guided tells the story of the group’s work in California, from the Hoopa Valley Reservation in Trinity County down to numerous villages in San Diego County.

Valerie Sherer Mathes has written about the Indian reform movement and the writings of Helen Hunt Jackson in other books. Jackson figures into this book as well; her first trip to Southern

California was in 1881, to write articles for Century magazine. That led to the book Century of Dishonor, which chronicled the mistreatment of Native Americans she witnessed. Jackson wrote the novel Ramona in hopes it would reach a wider audience and move them to political action; unfortunately, the book inadvertently made Native American culture a cause celebre, bringing tourists out to gawk at the people without motivating significant political action. Jackson’s books were

nevertheless on the reading list of every WNIA chapter, and her passionate advocacy informed the group even after her death.

WNIA president Amelia Stone Quinton’s work is thoroughly examined, too; her editorship of The Indian’s Friend, the newsletter that kept members informed about ongoing projects, and the occasional conflict between parties, holds much of the recorded history of this movement. Mathes points out a few occasions where a lack of inclusion in the newsletter speaks louder than words about the difficulties going on behind the scenes, or when brevity might have been sugarcoating reality.

The work of the WNIA did often benefit the Indians they set out to serve; many received quality education, food, lodging, and job skills, and attendance in the schools they founded was always in the highest demand. But the association’s members received benefits as well. Their work gave them a degree of political clout—lacking the vote, these women were masters of the petition drive—and taught them to network, lobby, and formulate sound arguments, tools that couldn’t hurt on the road to suffrage.

Mathes writes in an epilogue that to truly understand the WNIA’s impact, more research must be done into other women’s volunteer organizations and into individuals who disagreed with the WNIA’s practices and policies, among them Catholic organizers who resented the evangelical Protestant approach to Indian reform. For a first step, Divinely Guided covers significant ground as a work of interest to Native American and California historians, and a new view of women’s role in both.

Reviewed by

Heather Seggel

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.