Memoir and the Art of Making 'You' Universal

A memoir, almost by definition, is a work of narcissism. The main character is most likely you, and all that happens is filtered through your own perceptions. You’re the hero, the protagonist, the narrator, and readers are stuck with nothing but … you.

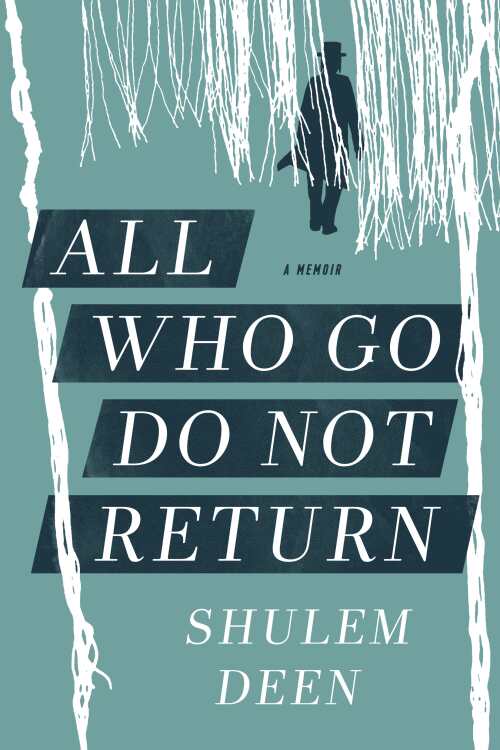

However, the best memoirs are not really about you at all. The good ones are those that help readers see themselves, too. They hit on themes of conflict, weakness, strength, insecurity, and danger that can be felt universally. Or, as Shulem Deen puts it, a memoir is not therapy. A memoir is about your reader. It focuses outward and not inward.

This is how Deen can write a book about a very specific experience—leaving an insular Hasidic sect—and make it seem universal. His memoir, All Who Go Do Not Return, recently won a National Jewish Book Award. It’s about his own struggles, and dangers, as he separated himself from his community and faith. But his message resonates beyond himself. Below the news, FTW talks to Deen about leaving Hasidism, the art of memoir writing, and his experience working with indie publisher Graywolf Press.

First, the News

Library Privileges: Once you’ve read from behind the library counter, it’s hard to go back. Foreword Reviews Associate Editor Michelle Anne Schingler, a former librarian, names the access points she’ll miss.

Works in Translation: Indie publishers are drawing world literature toward English-speaking audiences, and we couldn’t be more grateful for the access to these five fantastic books.

Parenting Hacks: Fulfilling? Yes. Easy? No. For those looking to make their parenting lives a bit more smooth, though, we’ve got some book recommendations to lighten the load.

Great Graphic Novels: These graphic novels, featured in our Winter Issue, are full of exciting quests and daring deeds. We hope that readers enjoy them as much as we did.

Featured Reviews of the Week

If You Were Me and Lived in…Italy, by Carole Roman. This addition to the globally attuned children’s series takes young readers to Italy, where they’re not only immersed in the culture, but are vicariously permitted to sample scrumptious Italian fare. Reviewed by Rachel Jagareski.

Man Interrupted, by Nikita Coulombe and Philip Zimbardo. Think men have it easy? This well-researched book takes a hard look at the struggles facing modern males. Reviewed by Amanda McCorquodale.

Loving Eleanor, by Susan Wittig Albert. Reporter Lorena Hickok met Eleanor Roosevelt when she was still just the wife of an aspiring politician, and the two fell in love. This fictionalized account of their relationship is both poignant and thoughtful. Reviewed by Michelle Anne Schingler.

The Assimilated Cuban’s Guide to Quantum Santeria, by Carlos Hernandez. Combines the strong Latin tradition of magical realism with a dose of science fiction to create an outstanding collection of short stories. Reviewed by Peter Dabbene.

Adulterous Generation, by Amy L. Clark. In environments that seem inhospitable to their needs, the characters in these short stories reject the status quo. Reviewed by Amanda McCorquodale.

Shulem Deen

Your book’s title represents the feeling in the Hasidic community that once you leave, you can never come back. But where are you now in your own relationship with Judaism?

Shulem Deen

I don’t currently have any religious orientation, so my relationship to Judaism, as a faith tradition, isn’t much to speak of. Although that is very different from Jewishness—the sense of belonging to a people with a strong and deep consciousness of history. That part of me is quite strong. Culturally, my attachment to Jewishness is expressed in observing some aspects of the calendar cycle (Hanukkah, Passover, etc), but also its values—an appreciation for intellectual rigor, a certain ethos regarding interpersonal behavior, and a sense of communal responsibility.

You mention influential Jewish writers such as Elie Wiesel and their tendency to romanticize Hasidism as a mystical form of Judaism, when in fact they’re simply rigid. Do you find this a common misconception?

What I mentioned—to be more precise—is that writers often conflate Hasidim (the people) with Hasidism (the teachings), when the reality is that actual Hasidic communities live by a more stratified set of practices, most of which have little to do with Hasidism. Typically, I think, these writers trade in some archetype of an eighteenth century shtetl-Hasid, which may or may not have an actual historical basis, but it is far removed from Hasidic communities in real life.

Is it common? Hard to say. On Twitter, I often see posts of aphorisms attributed to “Hasidic proverbs,” and they get retweeted a lot by—I guess—people who like such things. But I’m always amused, as if Hasidic life is notable for fortune-cookie wisdom. I think it’s the same impulse, though—to see the world of Hasidim as filled with profundity. Maybe it isn’t common—maybe I just notice it a lot, because it seems so ridiculous.

You said once that many writers mistake memoir for therapy. Therapy is all about healing yourself, but in memoir-writing the reader is the focus. How do you write about your life with an eye outward rather than inward?

The important thing, I think, is to recognize that a memoir (like all art, really) probably won’t be very good if it’s just a vehicle for self-indulgence. Practically, an appreciation for craft—the teachable (and learnable) aspects of writing—is essential, and it should be committed to in a disciplined way. It’s also useful to remember that your reader owes you nothing; if the reader’s interest isn’t the primary engine moving the work forward, the reader isn’t likely to keep reading, and justifiably so.

We focus on small presses and independent publishing. How was your experience working with Graywolf Press?

The thing about Graywolf—aside from being just a great publishing house in so many ways—is that everyone there is so extraordinarily NICE! Which was kind of surprising to me, because I thought of the publishing world was where writers go for the masochistic pleasure of having an editor make you feel utterly talentless and then you go home to weep about your sad life. But everyone at Graywolf was just so phenomenally supportive and kind—from the director to my editor to the publicity and marketing people. It’s my first book, so I can’t really compare them to anyone else, but I can’t imagine this is typical. Also, they’re in Minnesota. And apparently, “Minnesota nice” is actually a thing.

Memoirs have also been written about leaving the Amish community, Scientology, radical or insular branches of Christianity and Islam. Do you think your story also has a universal message beyond Judaism?

Reader feedback has been extremely diverse, with people from all kinds of faith traditions and backgrounds writing to tell me the book resonated. Especially people who struggled with faith—any kind of faith, Jewish, Christian, Muslim, SDA, etc. (And typically not from very insular backgrounds.) So while the setting is a Jewish one, I think the struggles I went through are relatable a lot more broadly.