Ten Shades of Destiny

Succor and Strife in This American Life

In this season of political, economic, and cultural crisis, what must our friends and foes on foreign soil think as American politicians crow about American exceptionalism, America’s best interests, and other dismissive and xenophobic ideas? Plainly, we have a systemic superiority problem. Is it justified? And, if so, what are some of the unique American qualities and advantages that led to our brand of democracy?

Yes, we have great founding documents in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, but so do France, India, and other countries. In his own series of essays from 1948, Columbia University historian Richard Hofstadter pinpointed a few sacred characteristics that resulted in America as we know it. Citing the writings of statesmen from the founding fathers to FDR, Hofstadter listed America’s expansive reliance on private property, economic opportunity, and competition as its game-changing factors. Such ideas found fertile ground to develop in America’s institutions of higher learning. Harvard founded the History of American Civilization graduate program in 1937; Brown soon followed; and the great American university presses proceeded to own the subject without looking back (figuratively).

Let’s look at ten outstanding books that enlighten our understanding of America. Some are provocative, others overtly studied, and a few requiring measured patience to see their arguments come into clear focus. Each will open our eyes to something unique about the American people, and, perhaps, help explain our prideful attitude.

In The Story of America: Essays on Origins (Princeton University Press, 978-0-691-15399-5), Jill Lepore, a longtime essayist for The New Yorker, fashions a series of elegant historical arguments with an endless stream of fascinating anecdotes and diverse quotes (not excluding gossip). Regarding America’s origins, she calls the study of American history “inseparable from the study of American literature … Literacy rates rose and the price of books and magazines and newspapers fell during the same decades that suffrage was being extended … Americans wrote and read their way into a political culture inked and stamped and pressed in print.” Lepore’s twelve essays study the ideas of America without “hero worship.” Captain John Smith, Jefferson and Sally Hemings, the Great Migration of blacks to the North, American homicide rates—familiar subjects, yet, after the Lepore treatment, profoundly affecting.

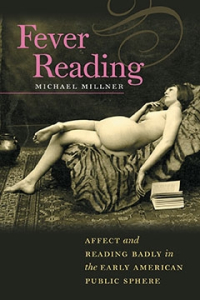

“The problem … is not physical or mental but a ‘depravity’ of morals’ … It ‘enervates’ and ‘enslaves’; it’s ‘deranging and debilitating.’ Madness and suicide may follow.” Such were the hazards of reading in the minds of a great many American leaders in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when the perceived dangers received far more attention than what were considered the benefits of reading. Fever Reading: Affect and Reading Badly in the Early American Public Sphere (University of New Hampshire Press, 978-1-61168-243-4) is Michael Millner’s contextual response to recent hand-wringing over social media, digital porn, and seemingly wasteful time spent online. Fever Reading argues that “such bad forms of reading are critical, reflective, and essential to modern democracy and the public sphere.” This is a fascinating and necessary investigation that would only ever have come to light in a university press; Millner dances among many different academic fields and dispels many hypersensitive suppositions.

Another grandiose story that defines the American way in some minds is the belief that FDR broke with tradition when, in response to joblessness and the Great Depression, he ushered in the New Deal and started the United States down the cozy path to a nanny state. In fact, we learn in The Sympathetic State: Disaster Relief and the Origins of the American Welfare State (University of Chicago Press, 978-0-226-92349-9) that Congress had previously dispensed federal funds in more than one hundred acts or resolutions to help citizens “recover from disaster or other circumstances beyond their control,” from the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 to the 1827 Alexandria Fire to pensions for Civil War veterans. With these precedents in mind, Roosevelt and others argued that the Depression was a “disaster” and that relief was constitutional—and also the morally right thing to do. Michele Landis Dauber deserves the highest praise for bringing the welfare conversation full circle in this superbly written and researched volume.

Both the Depression and the Civil War have earned immeasurable attention from historians, novelists, and filmmakers. That the War Between the States acutely affected other nation states, France, in particular, is detailed in Ruined by This Miserable War (The University of Tennessee Press, 978-1-57233-859-3), which offers the remarkable perspective of the acting French consul at New Orleans from 1863 to 1865, Charles Prosper Fauconnet. That Fauconnet was writing to a French audience (his superiors back in Paris)—mostly disinterested yet nonetheless shocked at the bloody conflict—required that he painstakingly explain the heavily nuanced issues. As the point man for his country in the raucous region, Fauconnet’s responsibility was great, and his Gallic consternation is palpable in the chronological transcripts. Translated and edited by Carl A. Brasseaux, with co-editor Katherine Carmines Mooney, Ruined by This Miserable War proves that there’s plenty more to say about the Civil War.

Such a never-say-never attitude is surely what motivated Guy R. Hasegawa to write Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs (Southern Illinois University Press, 978-0-8093-3130-7), offering a hopeful look at the fledgling individuals and companies that sought, through the design and production of prosthetics, to relieve the hardship of the combatants who lost limbs in ghastly fashion (more than 60,000 amputations were performed). Mesmerizing photos accompany many headshaking descriptions of inventive devices made from any number of materials, and we are compelled to marvel at the bionic progress that we’ve made to date.

Untold wealth and power did not befall any Confederate artificial limb maker, but our next post Civil War-era project profiles a Southern couple who did make their lucky strike: Katharine and R.J. Reynolds: Partners of Fortune in the Making of the New South (University of Georgia Press, 978-0-8203-3226-0).

This dual biography spotlights the post-Reconstruction South intent on writing an authentic American success story. Katharine and R.J. transcended their era in matters social, racial, economic, and matrimonial. Michele Gillespie offers readers of all persuasions an eminently readable take on the wonders and warts of one of the American South’s most compelling time periods. Let’s not forget that R.J. Reynolds’s great gift to America was Camel cigarettes, a splendidly addictive nicotine delivery product beloved by millions for its great taste and, for many decades RJR, like other tobacco companies, disputed credible research pointing to cigarettes’ cancer-causing agents, creating a legal defense model for any number of corporations.

In The Slumbering Masses: Sleep, Medicine, and Modern American Life (University of Minnesota Press, 978-0-8166-7474-9), we learn the similarly disturbing story of how certain sleep-aid makers (behind the recent proliferation of z-drugs) created the notion of sleep pathology by discrediting any sleep patterns other than one eight-hour block of sleep at night. Author Matthew Wolf-Meyer also details how industrial capitalism standardized factory shifts and working hours, which affected the sleep habits of many Americans over the past 150 years or so.

A great primer on the history and variability of sleep patterns, this book points to more flexible, realistic expectations of sleep to avoid both the drugs and the nights of insomnia.

America creates and consumes prescription drugs more profusely than any other nation, averaging between nine and thirteen prescriptions a year per person. Indeed, our drug habit is vital to the economy. But no individual is especially excited to get a prescription filled. Why are Americans, seemingly reluctantly, so willing to spend so much money on drugs? Joseph Dumit argues that it’s because we have been led to believe that “feeling healthy has become a sign that you need to be careful and go in for screening.” To be normal, he says, is to be insecure. In Drugs for Life: How Pharmaceutical Companies Define Our Health (Duke University Press, 978-0-8223-4871-9), Dumit points out exactly how and why big pharma has convinced us that we are ill and in need of chronic treatment. Where we once took drugs to cure an illness, it appears that we now swallow multiple drugs to prevent the possibility of illness. Clinical trials, too, are used as a surreptitious method to measure the size of a potential market and estimate profits. American health, it would seem, is being defined by executives in boardrooms, not doctors and lab technicians in hospitals.

Lots to fret about in this American life; at least our nation is still the unquestioned great global powerhouse with many bright decades ahead. Not according to a distinguished team of 140 international scholars, as detailed in Endless Empire: Spain’s Retreat, Europe’s Eclipse, America’s Decline (University of Wisconsin Press, 978-0-299-29024-5). By studying the rise and falls of the great European empires of the past five hundred years, a few distressing patterns emerge—one of which indicates that America is far down the slippery path. From the deterioration of economic strength needed to maintain military power in minor conflicts to fractured alliances between major powers, America seems destined to repeat some of history’s most notorious lessons.

America is a wonder of the Judeo-Christian world. Consider that we are the best-educated nation and also have the highest percentage of citizens who pray regularly. What? If God’s existence is impossible to prove, if this country values open-mindedness and a willingness to think freely about any and all subjects, if we hold as sacred our right to question authority and dogma, how can so many of us believe that an all-powerful, all-knowing creator listens to us and, at times, intervenes on our behalf? Such is the nature of The God Problem: Expressing Faith and Being Reasonable (University of California Press, 978-0-520-27428-0), and the issue has never been approached more thoughtfully, or strategically, than by Robert Wuthnow, the director of the Princeton University Center for the Study of Religion. Taking on this headiest of subjects, Wuthnow discerns that Americans don’t obsess about proving God’s existence but, instead, carefully parse their language to avoid making irrational claims about God. Indeed, most Americans don’t believe in the wrathful, vengeance-seeking biblical God. In their minds, Jesus is a conversational “buddy,” an imaginary friend. Even the idea of Jesus as a divine savior is uncomfortable for many “believers.”

Americans obviously have exceptional friends, imaginary or not, to turn to for guidance. Whether we grapple with a superiority attitude problem or the God problem, we cut a striking figure in world history. Bet against us at your peril.

Matthew Sutherland is a contributing editor to ForeWord Reviews.

Matt Sutherland