4 Great Indie Sci-Fi Titles for Summer

This collection of science fiction, all from our Summer 2016 Issue, all take place in a setting very much like ours, with a twist. While some sci-fi books throw the reader far into the future, these keep you grounded in our own time and then introduce the change in our own world. Have fun experiencing what the world would be like if time suddenly stopped or if you had to search for your family in the wilderness. Whether you find these books bizarre or believable, they’re each an adventure.

Invaders

22 Tales From the Outer Limits of Literature

Jacob Weisman, editor

Tachyon Publications

Softcover $16.95 (384pp)

978-1-61696-210-4

Buy: Amazon

The stories are what they need to be, and if that involves a doglike alien’s wordless meeting with a shepherd, so be it.

Jacob Weisman settles—or perhaps provokes—the debate about what constitutes literature, and what represents “genre fiction”–science fiction, in this case–in the story collection Invaders: 22 Tales from the Outer Limits of Literature.

With a selection of authors and stories that don’t always fit the traditional mold of science fiction, the title Invaders is not so much representative of the stories contained within, but rather of the “outsider” status of the authors. The list of contributors is impressive—Jonathan Lethem, Katherine Dunn, Steven Millhauser, W. P. Kinsella, and Junot Díaz, among many others—but these authors have made their names and reputations in mainstream literature, not science fiction.

Smartly, Weisman addresses the elephant in the room immediately, with an insightful essay about the blurred lines separating those two sometimes arbitrary categories. Then, it’s time to jump into the stories themselves, which vary in content and style from the wordplay of Amiri Baraka (“See, you’re intelligent.[..] I’m outtelligent.”), to Millhauser’s trippy mock nonfiction, to Kinsella’s bizarre and humorous story of an alien who becomes the Seattle Mariners’ mascot. There are also affecting stories to be found, stories that probe the future of humanity with imagination and compassion, such as Julia Elliott’s “LIMBs” or Deji Bryce Olukotun’s standout “We are the Olfanauts”.

Because of the book’s variety, it demands a sense of open-mindedness toward what constitutes science fiction. But the writing itself is consistently excellent, and occasionally exquisite. There’s never a sense of these authors “slumming” in genre fiction simply because they can, or because they were solicited for an anthology contribution; the stories are what they need to be, and if that involves a doglike alien’s wordless meeting with a shepherd, so be it.

At its best, science fiction surpasses simple, conventional tales of “invaders from space.” With wry wit and sincere affection, this collection shows us that many times, the invaders not only have good intentions but also have much to share.

PETER DABBENE (May 20, 2016)

The Mercy Journals

Claudia Casper

Arsenal Pulp Press

Softcover $17.95 (236pp)

978-1-55152-633-1

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

This complex tale puts global crises and personal crises hand in hand, and questions if morality must adapt.

Many dystopian novels feel distant, taking place in a time far from now, but Claudia Casper’s The Mercy Journals feels like it’s just on the other side of the door. Current global issues collide, causing disastrous wreckage out of which emerges a new social order, in this roller-coaster ride through the mind of an ex-soldier with PTSD.

Casper offers up the journals of Allen Quincy, an ex-soldier nicknamed Mercy. In the aftermath of war and a massive human die-off, Mercy has whittled what’s left of his life down to the smallest common denominator, moving between work and home and keeping to himself as much as possible. Until Ruby comes along. And then his long-lost brother, Leo. Convinced to travel into the wilderness in search of other lost family members, Mercy must confront his past and question the moral stance it has caused him to take.

There is a deftness to Casper’s writing that allows her to maintain control while juggling numerous complex layers. The combination of global problems explored here—climate change, war, refugees, famine—could easily become overwhelming, especially when combined with the sometimes erratic diary entries of a traumatized man, but each is given its place in the narrative, intertwined with Mercy’s own issues of loss and mental illness. Likewise, while many post-apocalyptic stories have a cast of characters that all feel the same way about their new world, here there are a number of reactions, often falling along generational lines. This complicated web is weaved with Casper’s lyrical prose: “Every movement she made, every sound she uttered was heightened, stripped bare, exposed in a raw clarity.”

This complex tale puts global crises and personal crises hand in hand, and questions if morality can stay the same or must adapt. It interweaves destruction with hope, individualism with socialism, and bouts of mental illness with moments of clarity, all while maintaining a strong plot and protagonist that carry the story forward. It will be an excellent addition to any science-fiction library.

CHRISTINE CANFIELD (May 27, 2016)

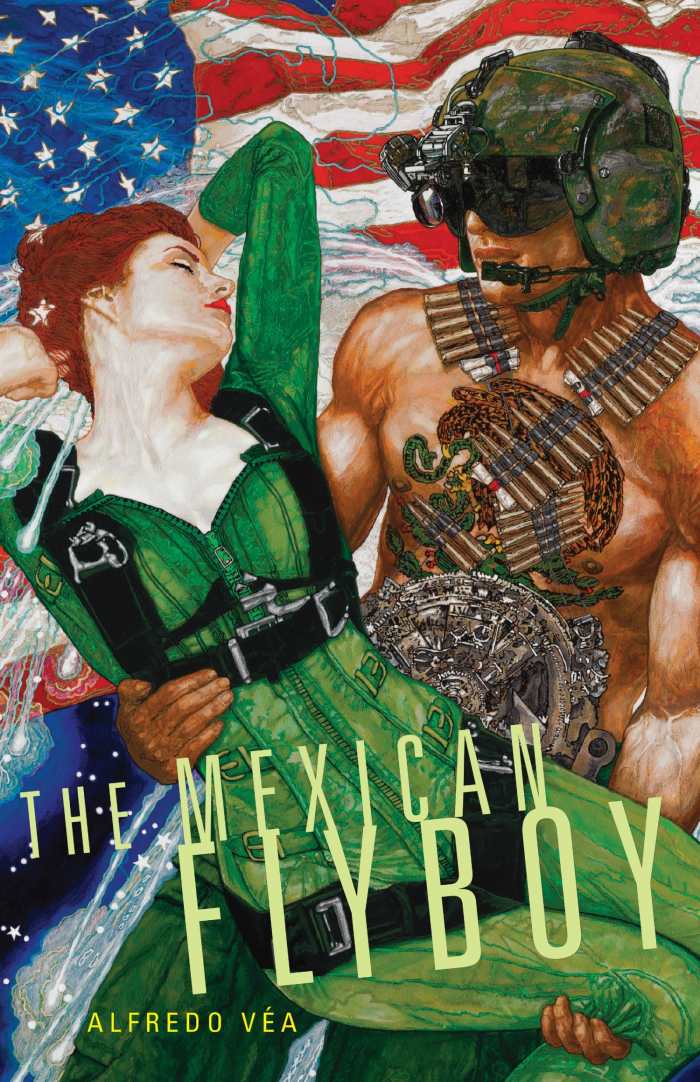

The Mexican Flyboy

Alfredo Vea

The University of Oklahoma Press

Softcover $19.95 (384pp)

978-0-8061-8703-7

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Anyone who enjoys magical realism would be committing a crime by skipping this remarkable piece of work.

Dreamlike and fantastical, yet strangely earnest, Alfredo Vea’s The Mexican Flyboy is a magical realist tour de force.

Simon Vegas is a self-made man with a dream: end human cruelty and suffering. As a soldier, he encounters the mysterious antikythera device, invented by Archimedes for the purpose of time travel, steals it, and embarks upon a series of surreal journeys through history … or, perhaps, through his own tortured past. All the while, he struggles to understand cruelty, to individually right every wrong ever perpetrated, and to resolve his own tragedy-marked past.

The Mexican Flyboy is both strange and beautiful, embodying the best of magical realism and literary fiction. In fact, Simon’s time machine is literally magic: a manifestation of his childhood obsession with magic and magic-based superheroes. The book openly embraces an almost childlike form of magical thinking, which adroitly reflects Simon’s early trauma and makes his character arc all the more satisfying at its conclusion. At the same time, the colorful, well-fleshed-out peripheral characters are generally well-rooted in reality. They provide an anchor to objectivity that reassures us that Simon isn’t completely crazy, that his quest may be true, at least in part.

The book apes the style and structure of pre-Code comic books brilliantly, evoking a literary whirlwind of sudden, fantastic deeds and abrupt plot developments. At first, this over-the-top style is bewildering. Yet Vea never loses the thread of the story, and the plot progresses clearly, never abandoning the audience. Though reminiscent of the style of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, this book is distinct and unique, far more invested in objective reality than Marquez’s world of layered metaphors.

The Mexican Flyboy is a book about which longer, more complicated analyses could—and should—be written. It is more an experience than a book, a piece of literature that grabs and transports. In fact, it is not to be missed, and anyone who enjoys magical realism would be committing a crime by skipping this remarkable piece of work.

ANNA CALL (May 2, 2016)

Thursday, 1:17 p.m.

Michael Landweber

Coffeetown Press

Softcover $13.95 (208pp)

978-1-60381-357-0

Buy: Amazon

Thursday, 1:17 pm is an unconventional and intriguing novel that blends thoughtful insight with an irreverent, anything-goes attitude reminiscent of Chuck Palahniuk.

Michael Landweber’s Thursday, 1:17 pm is a thought-provoking psychological fantasy. On a critically stressful day in his young life, seventeen-year-old “Duck” finds his world suddenly frozen in time, except for himself. He is the sole moving being in a world gone utterly and eerily still. Alone with his thoughts, he wanders through a world full of people paused in the middle of their daily lives: speeding cars frozen in mid swerve; jetliners fantastically hovering in midair.

Other writers, including Nicholson Baker and John D. MacDonald, have explored similar concepts, but unlike their protagonists, Duck has no apparent control over the freezing of his world, and no idea how to unfreeze it.

Duck is an amusingly sardonic and self-aware narrator whose deadpan observations about the physical practicalities of life in his new situation take the form of paragraphs from an imagined travel guide to the “frozen world.” He’s rather less perceptive about the emotional turmoil of his own life. Like most teenagers, he’s unstoppably curious about sex and friendship and love, and the puzzling nexus between them. Also, justice and equality. And death. And madness.

Landweber subtly varies the tone throughout the book. Some of the situations Duck encounters in his solitary existence are comical. Others are dangerous, discouraging, or titillating. (Who knew, Duck observes, that so many people take showers, or have sex, at 1:17 in the afternoon?) Some are frightening … especially those that bring Duck closest to the parts of his life that he’d like to forget, or never understood in the first place.

Browsing through a paused world may give Duck the chance he needs to reassess and reevaluate his own life, if he can ever find a way to restart it. If the solitude doesn’t drive him crazy. If he’s not already crazy. Or worse.

Thursday, 1:17 pm is an unconventional and intriguing novel that blends thoughtful insight with an irreverent, anything-goes attitude reminiscent of Chuck Palahniuk. It’s a fun read that also gives something to think about after its final page.

BRADLEY A. SCOTT (May 10, 2016)

Hannah Hohman