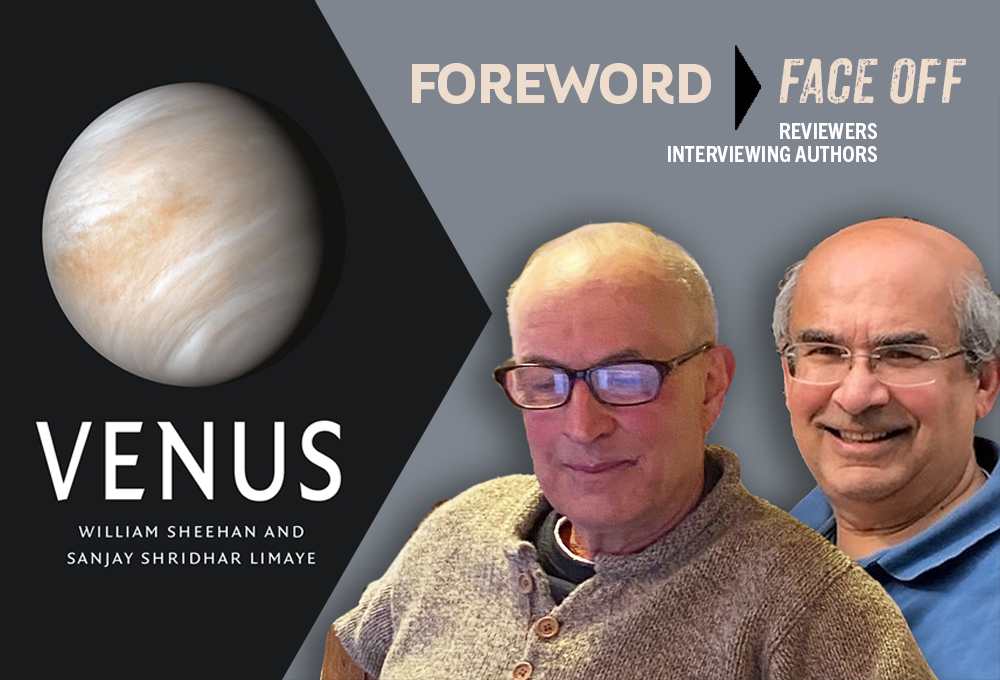

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews William Sheehan and Sanjay Shridhar Limaye, Authors of Venus

Story. You’ve been hearing a lot about the power of story, lately—the sensible realization that hard facts don’t fully explain what’s happening around us, and that many of us understand things better if knowledge comes wrapped in a story.

In olden times, before science filled in so many of the blanks humans had about the world, story was everything. Why is the sky blue? How deep is the ocean? What is the sun made of? These were the burning questions posed around campfires of yore, and storytellers did their creative best to offer up persuasive explanations—the birth of myth and legend.

And those handful of celestial bodies that meander through the stars—deemed planētēs by the Greeks, meaning “wanderer”—have earned the attention of skygazers for as long as humans could look up, none more than Venus. This week we’re thrilled to hear from the authors of a fascinating new book about that third brightest object in the sky, after the sun and moon. William Sheehan and Sanjay Shridhar Limaye’s Venus earned a stellar—couldn’t avoid that word—review from Rebecca Foster in Foreword’s July/August issue and she readily agreed to an authors-are-from-Mars, reviewers-are-from-Venus conversation.

What can you tell us about the Kosmos series, and how did you get involved in writing for it?

WS: Science historian Peter Morris, the general editor, contacted me some years ago about doing a Mars book for the series. As it turned out, I didn’t do Mars but I did Jupiter—then Mercury, Saturn, and now Venus. The books attempt to satisfy the needs of the general reader but aren’t afraid to tackle complexity and give particular attention to still active areas of controversy (for instance, the possibility of life in Venus’s clouds). In addition to relating what we know, they also try to introduce readers to the idea of making their own observations, whether with the naked eye, binoculars, or small telescopes. They are also lavishly illustrated, and quite affordable. I think they have nicely filled an important niche.

SSL: I don’t now recall when I first met Bill, but it was in the early to mid-1990s and we corresponded occasionally until about a decade ago. It was a pleasant surprise when I received an email from him in early January 2020 saying that he was approached by Reaktion Press about doing a book on Venus. He wrote that, given my research on Venus, I would be better suited to author the book. Having written only a few popular articles, I replied that a collaboration might be more successful. We discussed a general outline but wrote our chapters separately and then shared them. To provide a uniform voice and style, Bill did the magic with the material.

There’s a contradiction between people thinking Venus must be much like Earth, and the reality that it’s very different (and inhospitable). Where does this misconception come from, and what is it essential to know about the similarities and differences between the planets?

WS: The misconception comes from the fact that in earlier times—say, the century or so after the invention of the telescope—it was widely thought that the Moon and planets all had to be inhabited, on philosophical and even theological grounds, since why would God have made them if they were only to be bare uninhabitable deserts? Also, there was a fair amount of analogical thinking; as soon as it was realized that the Moon and planets were “other worlds,” it was easiest to interpret their surface features in terms of the one planet we knew—our own Earth. In addition, the Earth and Venus were almost identical in size and mass, so they were offhandedly called “sister planets.” Two peas in a pod, as it were.

SSL: What is essential to keep in mind is that although the two planets may have been similar in their infancy, their evolutionary paths diverged at some point. Today Venus spins backward once every 243 days, somewhat longer than the time it takes to make one circuit around the Sun. The formation of Earth’s moon through impact(s) may be an important factor in Earth’s evolution and current rotation rate. The tides raised by the moon have been significant over time. We do not know whether Venus ever had a moon which was lost and whether it ever had liquid water on its surface at some time, leading to possible origins of life on Venus. The present-day cloud cover on Venus is still hiding many mysteries.

Ancient civilizations knew about Venus and mentioned it in their legends and poetry. What would readers be surprised to learn about how it has been characterized over the centuries?

WS: Venus is an extremely impressive object as seen with the naked eye—in fact, it is the brightest object in the heavens after the Sun and Moon, can be seen as a point of light even in the daytime sky, can cast a shadow, etc. Not surprisingly, therefore, it played an outsized role in the mythologies and religions of the ancient world—and was usually (because of its beauty) identified with a female divinity (though not in India). She was, for instance, Inanna, the supreme goddess of the ancient Sumerian cuneiform temple-tablets, later identified as Ishtar or Astarte, of whom the poet Milton wrote, “Astoreth, whom the Phoenicians call’d/Astarte, Queen of Heav’n, with crescent Horns,” and widely worshipped throughout the ancient Middle East.

Apart from its brightness and sheer beauty, its motions are at once complicated and simple. It appears as the Morning Star for 260 days (close to the period of human gestation), then reaches into the evening sky and after 584 days (the synodic period) appears in the same position relative to the Sun. However, since the Earth is meanwhile moving, only after almost exactly eight years does it return to the same positions relative to the Sun and the Earth—so that, whatever Venus is doing tonight, it also did eight years ago, and will be doing again eight years from now. The eight-year-period was the first regularity discovered in the motions of the planets (by the Babylonians), and led to the great revelation that there was some kind of regularity and order in the heavens, the key insight in science. The gods (or, among the Babylonians, the interpreters of the gods—the planets) might rule over everything, but they gave indications in the form of omens, and their rule wasn’t simply autocratic or arbitrary. Humans could to some extent be let into the secret of what the Greeks later called the Kosmos.

In more recent times, the motions of Venus have figured in the grand expeditions launched in the 18th and 19th centuries to observe the rare transits of Venus—when Venus glides across the Sun—in the attempt to triangulate the length of the Astronomical Unit (the standard of distance used by astronomers based on the distance of the Earth to the Sun). Because these critical observations had to be made from observing stations widely separated on the surface of the Earth, expeditions to observe them were important in opening up unknown areas of the Earth’s surface to exploration (e.g., Captain Cook in 1769; his round-the-world voyage was originally planned in order to observe the transit of Venus, which he did from Tahiti). So, through Venus we have learned a great deal about the Earth itself—perhaps this would surprise readers.

We have 1950s military technologies to thank for some advances in our understanding of Venus. How has this interplay of interests pushed research forward?

WS: Sadly, ever since the slingshot and bow and arrow were invented, technology for our species’ penchant for aggression and war has been among our greatest priorities, and this has continued into our own time. So many technological advances were spurred by World Wars I and II—especially the latter, which saw the advent of the first rockets capable of reaching space (in Nazi Germany), the first infrared sensors that could be used to detect the heat of missiles (and also of planets), and the like. In each case, a technology whose development was funded for and often deployed first for warfare has subsequently found peaceful applications.

I think everyone recognizes that even the Apollo achievement (landing men on the Moon) took place only because of the intense competition between the USA and the USSR, and that the rockets that were developed were essentially modified ballistic missiles. The amount of money that was available for the US space program reached over four percent in the peak years of 1965–66 (from 0.1 percent in 1958), and this was almost entirely because of the importance leaders saw in demonstrating national prowess through space spectaculars. After the Moon landings, interest—and budgets—fell off. Even the scientific exploration of the Moon was largely an afterthought, and would not have happened but for the vision and lobbying of scientists like Gene Shoemaker. Before Apollo 8, the US mission that would beat the Soviets to the Moon (the first circumlunar mission), the Commander, Frank Borman, was so preoccupied with beating the Soviets that he didn’t even want to bring TV cameras along.

We hear of the search for life on Mars, but not on Venus! Indeed, you write that “life as we know it certainly cannot exist on the surface at the present time,” but the question of whether there has ever been life on Venus is more complicated. What are some of our best clues?

SSL: Confirming the presence of liquid water on the surface is a key piece of information. Clues may come from the missions to be launched in the coming years. Finding the presence of trace chemical species and the composition of the Venus cloud aerosols from the forthcoming entry process will also be useful. The cause of the ultraviolet absorption is a mystery that has led to the suggestion of possible life, so learning more about the absorbers is key.

“Men are from Mars, women are from Venus … “ Wherever did this planetary metaphor come from, and is there any value in it?

WS: Ultimately, I think, it came from humans’ tendency to personify everything, including the planets. Venus was brilliant, beautiful, a woman. Mars, with its reddish tinge (one of the few objects in the heavens that is noticeably red, and the color of blood) and flare-ups into angry brilliance followed by fading into a faint ember suggested the rather manic behavior of a berserker or one of the heroes thrust forward during one of the aristeia performances of the Iliad, and thus was almost inevitably associated with warfare, a generally masculine preoccupation. Some of this was incorporated into astrology, which still has a great deal of credence (along with many other superstitious beliefs) even in modern times.

So that’s the origin of it. As for whether there’s any value in it, perhaps as a metaphor. Simon Baron-Cohen, a leading British psychologist and expert on autism, has written a book called The Essential Difference, indicating that there do tend to be definite differences in the male and female brain, owing largely to the effects of testosterone on brain development—men tend to be more analytical, focused on understanding how things work; they are what he calls “systematizers,” while women are more empathic and better at understanding people and social situations. Of course, culture has a great deal to do with this, but there’s still probably a general trend that’s biologically determined.

SSL: The red “angry” planet being associated with the aggressive human traits associated commonly with one gender and the feminine traits attributed to Venus are cultural stereotypes. I doubt if there is any real value in it except to foster more thoughtful discussion of the differences and commonalities.

Rebecca Foster