Reviewer Michelle Anne Schingler Interviews Mira Z. Amiras, Author of Malkah’s Notebook: A Journey into the Mystical Alep-Bet

Religion has lost its touch—just check out the latest polling numbers.

And there’s a case to be made that this turn away from God portends civilization’s demise, but we’re not of that school. What’s happening might just be a sort of reset, a different approach, a refreshed membership status that doesn’t require total compliance.

Religion, historically, has served many purposes, not least as a guide to explore our existence on this earth. And while all of our big dog religions rely on the supernatural to build formal systems of belief, many people of this day and age are attracted to how the great architecture of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism (and others), can be internalized, made their own—and the club membership just doesn’t mean much anymore. These people see religion as an internal combustion support system while they deal with life’s challenges.

Yes, you’d be correct to guess that this week’s interview between Mira Amiras and our Editor-in-Chief Michelle Schingler sent us off in such a ponderous direction. Mira’s new book, Malkah’s Notebook, made such a splash when it arrived in our offices that their conversation was preordained.

Speaking of Michelle, she needs reviewers. If you think you have what it takes to join our review team, email mschingler@forewordreviews.com

Malkah’s father is immediately receptive to her Kabbalistic and Talmudic inquiries, which I loved-perhaps because there’s a traditional sensibility that these are not always women’s spaces. Can you speak a bit to why you wrote him as such?

In the film it is made clear that Abba is not immediately receptive to Malkah’s inquiry. First, she brings Abba a picture of an oud she has drawn, yearning to learn to play. And he doesn’t notice her. It’s not until she asks the question that unlocks his receptivity and her “potential” that he begins to teach her. And that is on the letters of the aleph-bet, the תא . In the book, the answer lies only in an illustration of Malkah as a girl. When she’s really thinking hard, she is shown with “payes.” This is a hint that her father sees her as a boy worthy of entering his library and beginning his studies.

In the commentary/memoir, my father called me by a boy’s name when I was growing up and treated me as he would his son. I went to Hillel Hebrew Academy in Los Angeles, a half day Hebrew-half day English day school. But when we moved up to Oakland—and my father became the director of Jewish education for Alameda and Contra Costa counties—there were no day schools that took girls. So instead, he sent me to study privately with an old rabbi, a Holocaust survivor, who needed the work, and he taught me himself, and took me with him, introducing me to Jewish cemeteries, living dignitaries, ancient book collections, etc.

The short answer, I suppose, is that Malkah’s abba, my papa, both had a “traditional sensibility” as well as an innovative, future thinking mind. Some said that making the protagonist a girl would limit my audience, (“Chabad won’t like it”), but I told the tale the way it happened: my father chose to teach me—and Malkah’s Abba did the same. All they had was just the one daughter, and they had to make do, treating their daughter much like a son, and teaching her. Later, however, my father attracted a number of young men whom he mentored. And I always felt the love between them was more powerful and intimate than what we had ourselves when I was young. I suspect that Malkah’s father did the same after she left home.

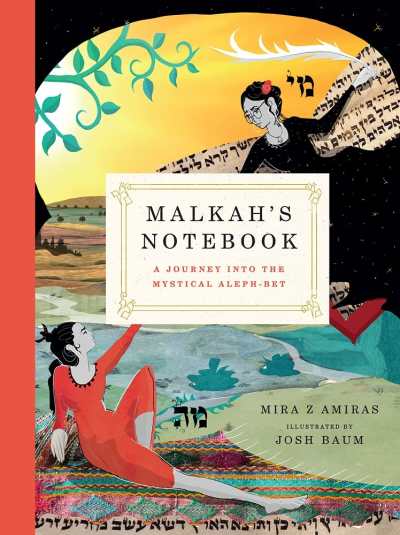

A middle section of the book, in which Malkah’s father is discussing the four sages with her, is illustrated in black and white, a marked departure from the vibrant colors of surrounding sections. What is that palette meant to convey?

All of part II, Sages in Paradise, takes place in Abba’s dusty old library, so the entire section is in blacks, whites, and shades of gray. We are inside the stories inside the library. This is first illustrated on page 91, but is later emphasized in part IV from Malkah’s point of view—that she does not experience the outside of books: instead, the library is filled with their guts, their insides. This was the best way I could depict what the library feels like, and explaining it to Josh, he was able to capture it). Part IV—which is all first person, being Malkah’s thoughts inside her notebook—is where she braids together her experience of the dusty old library with her experiences of the world.

To understand the meanings behind and within Hebrew texts and letters, Malkah travels the world and immerses herself in a variety of differing cultures. Judaism is a singular religion, of course, but I loved this intimation that its truths are connected to the truths of other religions, too. Is it your sense that spiritual seeking should lead to such comfortable coexistence, and if so, how so?

The commentary/memoir part of the book explained it thus (shortened here): “When my son was maybe 5 or 6, my father gave him a book of bible tales. One night I heard a scream from upstairs. I ran up to see my son in a panic: why did God want Abraham to kill his son? It made no sense, and my son was terrified that it could happen to him. After trying to comfort him, I decided to ask the wisest sages I knew and get him the best answer—since I did not have an answer that would help him. I asked rabbi after rabbi. One said Abraham was wrong, one said “everyone has to make a sacrifice for God.” One, my mentor, Reb Zalman Schachter Shalomi, said, “such a blessing to have a son who can ask such questions” (which in the book is attributed to Abba).

I knew these were not answers that would soothe my son. So I complained to my father. And he said, “in those days, the religions of the region demanded human sacrifice. In this story, the God of Abraham starts with what is expected—and then stays the hand, turning it to animal sacrifice instead: a paradigm shift in religious practice in Jewish tradition. Context, the religions of surrounding peoples, helped make rational sense of the tale.

And so I brought my father’s answer to my son. My father’s comparative approach was good enough for me and for Malkah, and set me on a path of anthropological studies, and Malkah to archaeology, but it was not good enough for my son. He had kept reading, and pointed in the book of tales, “so why does God smite the firstborn of the Egyptians?” he asked. My son’s career path seems to have been set by this event as well: he applied to law school, and in his essay told this story of why he wasn’t applying to seminary instead.

In sum, what my father taught me, if not my son, is that context is critical in understanding the origins of ritual and belief. And that if we trace context well into ancient times, what we may discover is our common roots with other peoples and traditions. And that each tradition took that ancient tale or knowledge in a different direction. But it need not be construed as an opposing direction. (My father used to long for kosher beef ribs in restaurants and complained that they should serve halal meat in restaurants for “all the rest of us.”)

In the example above, to the Jews, God stayed the hand of Abraham at the throat of his son Isaac. To the Muslims, God stayed the hand of Ibrahim from his son Ismaiel—not Isak—for they believe that Isaac’s name was inserted into the biblical tale where Ismaiel’s should have been. It would seem that a “comfortable coexistence” could not be achieved between these vastly different interpretations. But by focusing on the commonality—God stayed the hand of Abraham and substituted animal sacrifice (which is celebrated each year at Eid el Adha ((Eid El Kebir)) for Muslims, and at the blowing of the shofar at Rosh ha-Shanah for Jews), then an acknowledgement of God’s demand for the cessation of pagan human sacrifice could bring Muslims and Jews together into accord in their appreciation of the common divine. (There’s a lot more to say on this.)

Malkah spends considerable time in pursuit of understanding and spiritual illumination; even though I would consider her tale a triumphant one, she experiences some hard losses in the process, including the chance to see her beloved parents again. What do you think she and her father would say to each other, given the chance for one last conversation over his old, dusty books? And what might she and her mother discuss?

The last part of the question—what might she and her mother discuss—is what the epilogue is about: if Malkah could resurrect, and this time be safe and sound and whole in her mother’s arms, her questions would be quite different when she was ready. Her questions revolving around Lech L’cha ךל ךל would start with the two mothers, Hagar and Sarah, and the powerful differences between the traditions that emerge from each—(the commentary addressed this in more detail).

With her father—this is only hinted at in the passage quoted from Zohar, in Pinchas, Vol 9 of Daniel Matt’s translation and commentaries of the Pritzker edition of Zohar. If Malkah is anything like me, her questions for her father continue to rise within her every single day since his death. And every discovery she makes, she silently reviews with him. On any topic. Every topic. For his part, he would slap her on the back of her shoulder and with a broad smile, encourage her to continue her investigation. He might hand her another book or two, but no answers would be forthcoming. Just the pleasure of his company.

The meanings that your book draws out of Hebrew letters are, admittedly, meanings that were foregone in my (academic setting) Hebrew course, and yet I found myself pulled to them in a way that made me wish this book had been taught alongside our lexicons and course texts. Can you see a place for Malkah’s story in Hebrew coursework, and, if so, how should it be integrated?

Ah, of course! Thank you so much for asking. This book emerged out of a course I used to teach at the university called Jewish Mysticism, Magic, and Folklore. So yes, it’s teachable the way, I suppose, a graphic novel is teachable. To this end, I’ve already starting putting out a number of pdfs (easily updateable) under Teaching Docs at academia.edu for this purpose. These include: Malkah’s Study Guide, which identifies the principle, question, subject, or point; context; key to unlock illustrations, and a reference or two for each section and two-page spread.

The Study Guide currently is about five-pages. A Glossary of Hebrew Letters, which includes symbols and meanings attributed to each letter (including the sofits), is currently four pages. Part V—Crumbling Old Books in the Dusty Old Library (if you care to slip between the covers), which is a fifty to sixty page annotated bibliography of sources, with page numbers correlating to the original version of Malkah’s Notebook. Part V currently resides in my drafts folder at academia.edu, along with other earlier versions of the book.

Malkah’s Notebook and these (and other) additional sources can easily be added to the curriculum of Hebrew Studies classes, help bring the letters to life, and teach a pedagogy of letters to deepen the student’s relationship not only with the letters, but also with Hebrew grammar and the hidden dimensions of the letters. Last thought here—I can also post on academia.edu my original course syllabus on Jewish Mysticism, Magic, and Folklore for anyone wishing further teaching materials. In Malkah’s Notebook, the aleph-bet is introduced through the orientation of the Sefer Yetzirah—that is, as Mother Letters, Doubles, and Elementals, rather than through an Aleph-BetGimmel approach. So the book is also a good adjunct to any class on Jewish mysticism that includes or wants to include the Sefer Yetzirah or Aleph-Bet Mysticism.

We perhaps default to thinking of creation as that which happened a long time ago, but your book discusses it as that which is ongoing, and something that we all have a place within. What do we gain when we shift our thinking in this manner?

The book shifts between linear time (Malkah’s own developmental timeline) and mythical time (time that has no timeline, but rather eternal existence). The epilogue adds cyclical time into the mix with the notion of Gilgul, with a very brief entry into the domain of rebirth/reincarnation. It does not go into the recirculation of souls, however, but opens the door to explore it. I believe we fill our lives with all three types of time, whether we need to or not. Linear time helps us think developmentally, with comforting rituals that mark our time on earth from birth to death. Mythical time helps us appreciate creation and the cosmos in a timespan too vast for many of us to contemplate linearly. And cyclical time gives us the courage to plow through with the hope of a do-over of sorts, reassuring us that we can try again, that we’ve been here before, or that we can hope to improve our lot next time round.

This last also helps us explain deep resonance with others we encounter, feelings of déja-vu, and certain mystical states of consciousness. Inhabiting these conceptually different notions of time helps us compartmentalize domains of existence in a more orderly fashion (not sure “orderly” is the right word here) and helps us distinguish the sacred from the profane, or the ordinary from the extraordinary, in a way that elevates one from the other and allows us to more easily shift between these quite different states of consciousness. (This, I suppose is the quick answer!)

Michelle Anne Schingler