Reviewer Melissa Wuske Interviews Shelly Tygielski, Author of Sit Down to Rise Up: How Radical Self-Care Can Change the World

With eyes wide open to the thorniest social and environmental problems, we take comfort knowing of the common folks improving their local communities one tiny step at a time. Such humble efforts are a reminder that change doesn’t happen instantaneously, and that each of us can perform small, daily acts to make the planet a better place.

This week’s guest, Shelly Tygielski, would also like to point out that healthy communities are built on an interdependence between helper and helpee. And to establish that interdependent relationship, it is crucial that the people who offer support, also ask for it—that accepting help shows strength, not weakness.

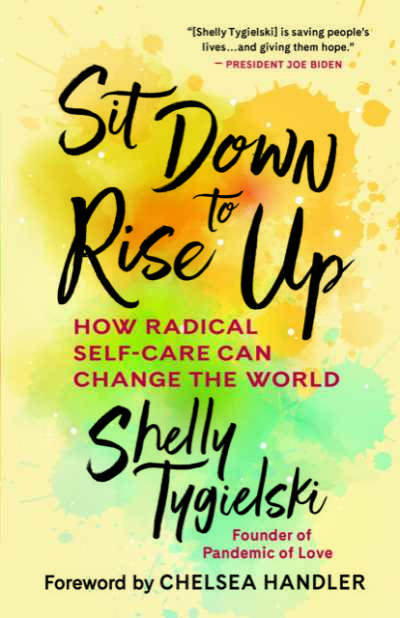

Shelly’s Sit Down to Rise Up: How Radical Self-Care Can Change the World earned a starred review from Melissa Wuske in Foreword‘s November/December issue, which clued us into the book’s extraordinary message. Forgive us for being greedy during this week of giving thanks, but we wanted more from Shelly.

Enjoy the interview!

The book shows that self-care is not a begrudging necessity; it’s actually an integral part of community transformation. Helping others doesn’t mean self-denial, even though that’s what so many people believe. Why has this lie been so deeply rooted in our society? How has it held us back?

I think it starts with the fact that the terminology we use is “self-care” and that the word “self” is in there. Words matter. When we say “self,” it automatically conveys an individualistic approach to care for most people. However, when we are rooted in deep contemplative practice, and we’ve sat with the uncomfortable and dug into the shadows, we begin to understand that our “self” doesn’t end where our physical body ends. Our “self” extends to every life we touch, every act of kindness, each word we speak and the intentionality behind how we show up each day.

Perhaps then, the better terminology—a suggestion I put forth in the book—is “communal care.” When we have a truly formalized system of communal care, the burden of having it all together and the challenge of having and being enough at all times is no longer squarely borne by one set up shoulders, rather it becomes the responsibility of our communities to lift us up, and thus, our responsibility to lift back when we can.

You ask how this lie has been rooted in our society and the fact is that this wasn’t always the case. If you look back to the Baby Boomer generation and every generation before that, we truly knew our neighbors—what they were going through, whether it was an illness or a job loss. We were connected to each other in a manner that is very similar to a thriving ecosystem; whereas today, each individual is expected to be their own micro-ecosystem and that is not feasible. I think the degradation of this communal approach has a lot to do with the fact that our places of worship and religion, in general, are less popular, as well as the fact that we have gone through a technological revolution that eliminates the need for interaction with each other beyond just a transaction. We need to get back to the basics: true human connection.

The stories of individuals are vital to community growth. They help bridge the divide between helper and helped; they fuel a belief in abundance, that there’s enough for everyone. What is it about personal stories—like yours, which you share in the book—that’s so powerful? How can people who are reluctant to share their stories begin to open up in shared community?

The need to share our stories is literally encoded in our DNA and there is actual scientific proof for this. Neuroeconomist Paul Zak has studied how when we hear a story, our brain releases cortisol and oxytocin, which are chemicals that we know trigger our ability to connect, empathize, and make meaning. This is what makes us uniquely human. Jeff Goins wrote in The In-Between that we are all experts of our own lives, and we all have something worth sharing with others that can make a difference.

For years I have been journaling for myself. Pouring my life into a pink diary with a little lock beginning in third grade and then elaborately writing in beautifully bound leather journals in my twenties. But it wasn’t until I started to share my stories with others that I realized how connected we all are, how similar our stories are and how important to others’ healing our stories can be. When people are afraid to share their stories—because of the potential reaction, for example—I implore them to at least write it down, even if it stays hidden away for a few years or more. Then I ask them to consider this question: What if owning and living our best stories meant that other people’s lives could heal and change? What if it would make someone understand that they are not alone? Would you share your story then?

For those new to mindfulness and self-care, what’s a good transformative practice to start with?

I always tell people to start with the simplest thing that is available to all of us: our breath. Our breath is portable, it doesn’t require a battery, and it is always there from the moment we wake and even in the moments we are in a deep state of sleep. I remind people that meditation can begin with a simple pause—ten seconds, fifteen seconds, sixty seconds. It doesn’t need to be a formalized practice initially. It can look like a “reset” between activities to help ground us and help us to show up more fully with a different quality of presence. I’ve often read that as healers and teachers, we need to “meet people where they are,” and I think that we need to apply that to ourselves, too. We need to meet ourselves where we are right now, in this moment of our lives, without setting expectations that we can’t live up to in this moment. Fifteen seconds of conscious breathing, a simple box breath or a 4-7-8 breath, is doable. Do what is doable first and don’t discount how much impact that can have. It helps you start somewhere.

Give a quick snapshot of Pandemic of Love—how the organization started, how it’s grown, the impact it’s had.

Pandemic of Love started around my kitchen table in South Florida. I was feeling distraught over the impending shut down that I knew was coming to our state, too. I was already very much a community organizer and had a community of over 15,000 meditators that were important to me and that I felt responsible for. I knew that many of these individuals were already struggling pre-pandemic to make ends meet and get to the end of each pay period, barely scraping by. Many of these individuals depended heavily on organized programs such as free breakfast and lunch at their children’s schools, covering ten meals a week for them. So the type of things that were swirling in my head at the time including questions like: How would they feed their children and keep the lights on? Did they have Wi-Fi so their children could continue attending class? Or a computer for that matter?

I felt a moral obligation and inherent responsibility to do something to help ensure that everyone in our community had enough, and I knew that there were many in our community—myself included—that had more than enough. In an informal way, our community had already been engaging in mutual aid for years, connecting a person in need with a person who could fulfill that need—everything from helping someone find a job, to giving them a ride somewhere, to helping pay medical bills. I decided in that moment on March 14, 2020, to formalize the process and to help connect people within our community at a time of disconnection.

Not being a technologically savvy person, I went on Google Forms and created two simple forms: GIVE HELP and GET HELP. I created a short video and posted the two links on my social media pages, thinking that only people in my community would see them. I was shocked to see how in a matter of a few hours, the links made their way around the world and were being amplified by people like Maria Shriver and Kristen Bell and Debra Messing. The organization grew from two simple forms to over 280 hyper-local microcommunity chapters across sixteen countries in less than eighteen months. Our over 2,000 volunteers have matched over two million people who have directly transacted over $60 million between them.

The most beautiful part about it all is that Pandemic of Love is not a non-profit—we are a non-profit disruptor—which is a term that Forbes magazine used to describe us. This means we don’t handle any funds, but rather, we connect donors with recipients directly—there are no fees, no overhead, and no red tape. Just a grassroots organization that is run purely on love and kindness.

What was your biggest surprise in starting Pandemic of Love?

My biggest affirmation—which was not surprising necessarily but served as a reminder—is that, yes, biological diseases can go viral, as can things like hate and fear, but so can love, kindness, and hope. Love is a virus, too, in that sense. And love can also be the cure, the salve that can heal all wounds.

What’s next for Pandemic of Love and for you in the months ahead?

Pandemic of Love now has an advisory board, and we are steering it in the direction of becoming fully autonomous, built and run by the people, for the people. We are gathering best practices, creating formalized standard operation procedures, and planning to improve the back end of the website to allow for mutual aid communities across the world to continue to form, weaving safety nets into the fabric of our lives.

I am currently promoting my book, Sit Down to Rise Up: How Radical Self-Care Can Change the World, and I am in the process of writing a second book, with my friend and someone I teach with often, Justin Michael Williams. The second book is called How We Ended Racism, and it’s going to be out in 2022. I am continuing to teach in different capacities and have some keynote speeches lined up, but to be honest, I am going to also be taking my own self-care advice and retreat some in the coming months to reconnect with myself and my family and commune with nature.

Melissa Wuske